Silvino Alexander ’22 was in Merion Hall when he first heard about a shooting near campus last week.

Alexander said he saw multiple news helicopters overhead on Oct. 26. Initially, he heard from friends via text and news alerts that a police officer had been shot. But, after looking for more information online, Alexander said he learned a Philadelphia resident had been killed.

A Philadelphia police officer shot and killed a 31-year-old man on the 5700 block of Overbrook Avenue. The man was later identified as Koffi Dzima, and the two officers involved were identified as Officer Julian Jones and Officer Cindy Williams-Dorin. Jones was also shot in the leg, possibly as a result of “friendly fire,” according to multiple media outlets. Police have neither confirmed who shot the officer nor released body camera footage, citing the incident as an “ongoing investigation.”

“I didn’t even know that the other person in the situation was shot and killed,” Alexander said. “I knew there had been an ice pick or something like that, but they didn’t have a gun. That opened my eyes a little bit more to the situation.”

Linn Washington Jr., professor of journalism at Temple University, has been working as an investigative journalist for 46 years and specializes in social justice, race-based inequities, the news media and law. Washington said media plays an important role in shaping how communities understand issues in their area, including any event that involves police violence.

“The framing of that event is from the police perspective,” Washington said. “They’re the ones that put that information out and needless to say, if it is an incident that involves police acting in a way where they use force, many times they will frame their response, put the narrative out, in the way that best represents the police.”

Melissa Logue, Ph.D., assistant professor of sociology, said this narrative, which the media often passes along without questioning it, is reflected in both headlines and in the way the story is reported.

“The police narrative may be true, but it may not be in some aspects that do not reveal themselves until later,” Logue said.

According to Police Commissioner Danielle Outlaw, speaking at a press conference about three hours after the shooting, Jones and Williams-Dorin were responding to a dispute between a landlord and tenant on Overbrook Avenue. Outlaw said the officers were met by Dzima wielding a hammer and pickaxe and, after refusing to drop the weapons, one officer fired his taser, knocking Dzima down.

Outlaw said the dispute moved outside where the man attacked the officer with the weapons, and the officers then discharged their guns. She said Jones was shot in the leg. Dzima was pronounced dead upon arrival at Lankenau Hospital, Outlaw said.

Like many members of the St. Joe’s community, the narrative of the shooting that Alexander first heard focused on the shooting of the officer by a man with a pickaxe and a hammer who had attacked the officer. That is what Keith Brown, Ph.D., professor and chair of sociology and criminal justice, said he initially heard.

“The first thing I heard was that a man shot the police, or the news story hinted that the man shot the police. And then a few hours later, it kind of shifted to a police officer was shot,” Brown said. “They implied that it was the person they killed, but they didn’t say that.”

About five hours after the Oct. 26 shooting, Arthur Grover, director of the Office of Public Safety & Security, and Cary Anderson, Ed.D., vice president for Student Life and Associate Provost, sent a University Announcement to the St. Joe’s community, informing faculty, staff, students and families of the incident.

The announcement said the incident “resulted in gunfire to subdue one suspect who was actively attacking police. The police quickly had the situation under control and informed the University.”

“That just really angered me and really saddened me because a man was killed,” Brown said. “And unless we’re outraged every time a city resident or any resident is killed by gun violence, this is never going to stop. ‘Subdued,’ to me, sounds like doublespeak. It sounds like you’re trying to lessen something serious that happened, and I know that may be appropriate for police language, but this man was not subdued. This man was killed and that’s deep.”

Anderson wrote in response to written questions from The Hawk that the language in the announcement “reflected how it was reported to the University at the time of the incident.”

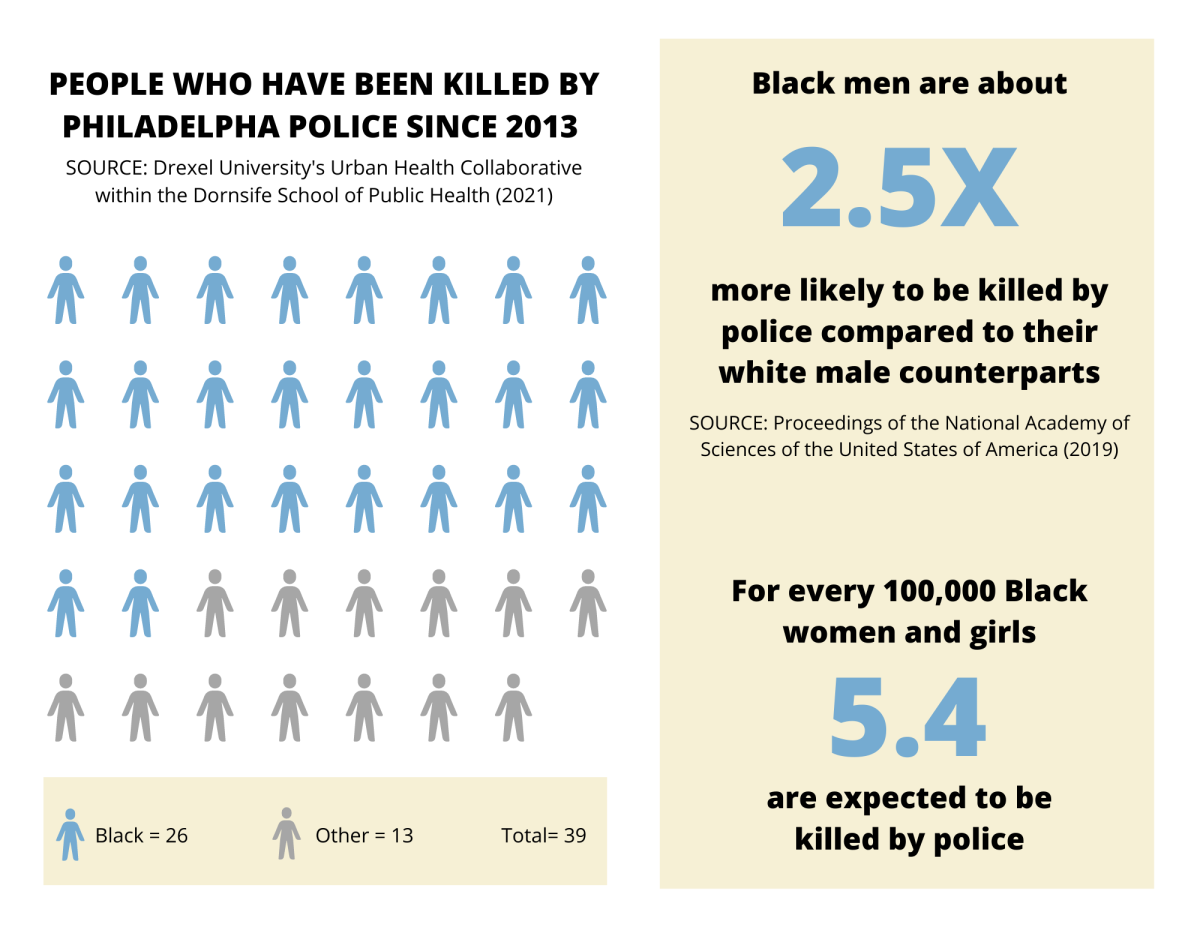

39 people have been killed by Philadelphia Police since 2013, according to February 2021 data from Drexel University’s Urban Health Collaborative within the Dornsife School of Public Health. Of those, 26, or about two-thirds, were Black.

Nationally, Black men are about 2.5 times more likely to be killed by police compared to their white male counterparts, according to a 2019 study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. And for every 100,000 Black women and girls, 5.4 are expected to be killed by police.

Washington said there have been multiple incidents of police providing incorrect information to the media. Just last month, Philadelphia Police and SEPTA officials produced inconsistent stories about a woman passenger who was raped on a train.

Washington said especially in urban areas, reporters tend to address these stories using only the details provided by the police. While police may not have all of the information detailing an incident right away, media outlets are responsible for constructing a holistic narrative, he said.

“Journalists should do what journalists are supposed to do, which is report and not repeat,” Washington said. “Yes, you need to get information from police and yes, you’re supposed to repeat that accurately. But that doesn’t end your possibility and duty as a journalist.”

Mike Lyons, Ph.D., professor of media and communication studies, was attending a screening of “Change: Exploring the Concept of Justice in America” in Forum Theatre when he found out about the fatal shooting.

For Lyons, being at this particular event on the night of the shooting was poignant, prompting him to think about how the stories of police violence in communities around campus are told through the lens of the media.

“It’s established in the news consumer’s head that this is a place where bad things happen because we don’t have any good news that comes out of these places,” Lyons said. “We don’t understand these places except for the context of crime.”

Lyons said it’s important not to think about crime as episodic but rather step back and look at the bigger picture of systemic racism and injustice in policing.

Susan Clampet-Lundquist, Ph.D., professor of sociology, was on her way to campus for the same event Lyons attended when she heard about the shooting. She said it is important to help students understand the root problems of violence.

“Part of our goal is to lay this foundation so that we can have conversations that are built upon a knowledgeable foundation, so we’re not just talking about things in an uninformed way, but we’re understanding the context a little bit better,” Clampet-Lundquist said. “We want to make sure that our students have this grounding of knowledge so that they can be thinking critical questions, and they can be informed in how they ask the questions.”

Eddie Daou ’22, Allison Kite ’22, Mitchell Shields ’22, Tayler Washington ’22 and Elise Welsh ’22 contributed to this story.