Durban, South Africa — For the students of Zanele Nsindane, an educator and head of the art department at Phakathi Secondary School in the township of Klaarwater, art offers an escape.

Some students and their families are still recovering from floods that devastated communities in Durban in late April. Many students walk up to 45 minutes from their homes to the school. Those from low-income households in the community may not have had a meal in the morning, and many do not have pencils, let alone a paintbrush.

“They get charcoal from home,” Nsindane said. “They don’t buy charcoal because most of them live in informal settlements, so they cook outside. They take the charcoal from the wood and use it for their art.”

For canvases, the students use recycled cardboard.

“The school pays for pastels,” Nsindane said. “That’s the only thing they have. They find cardboard and bring it to school to use as a canvas. They don’t do photography, [because] they don’t have access to cameras.”

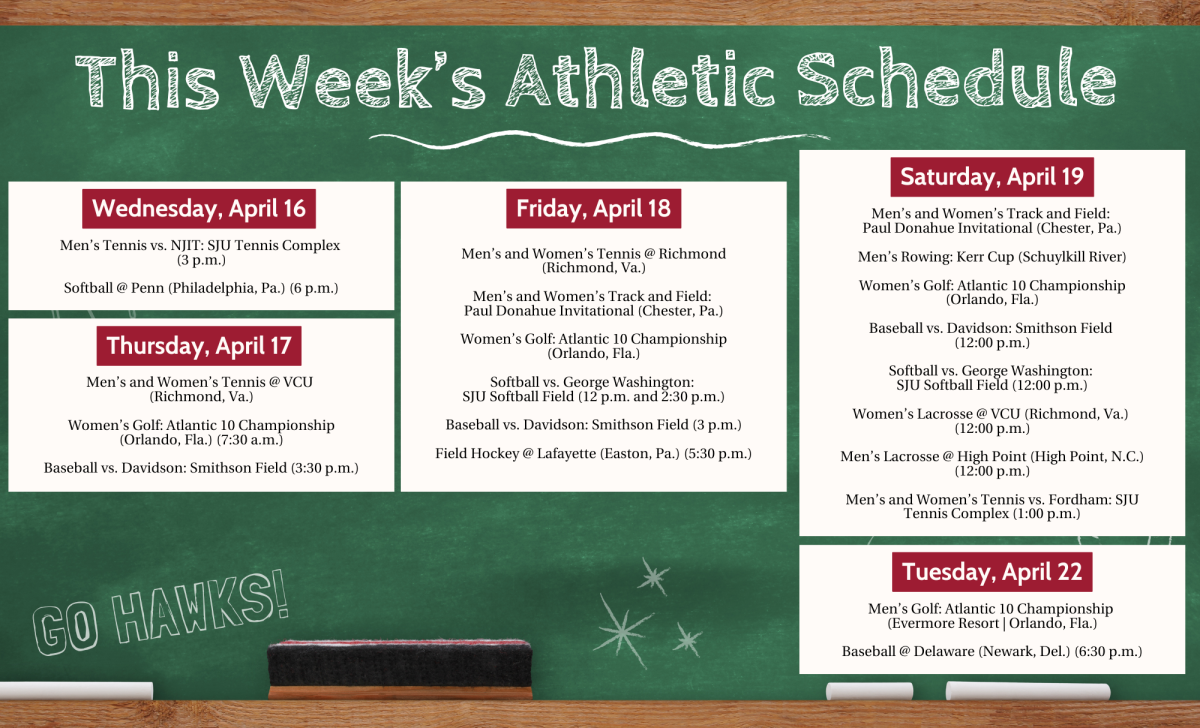

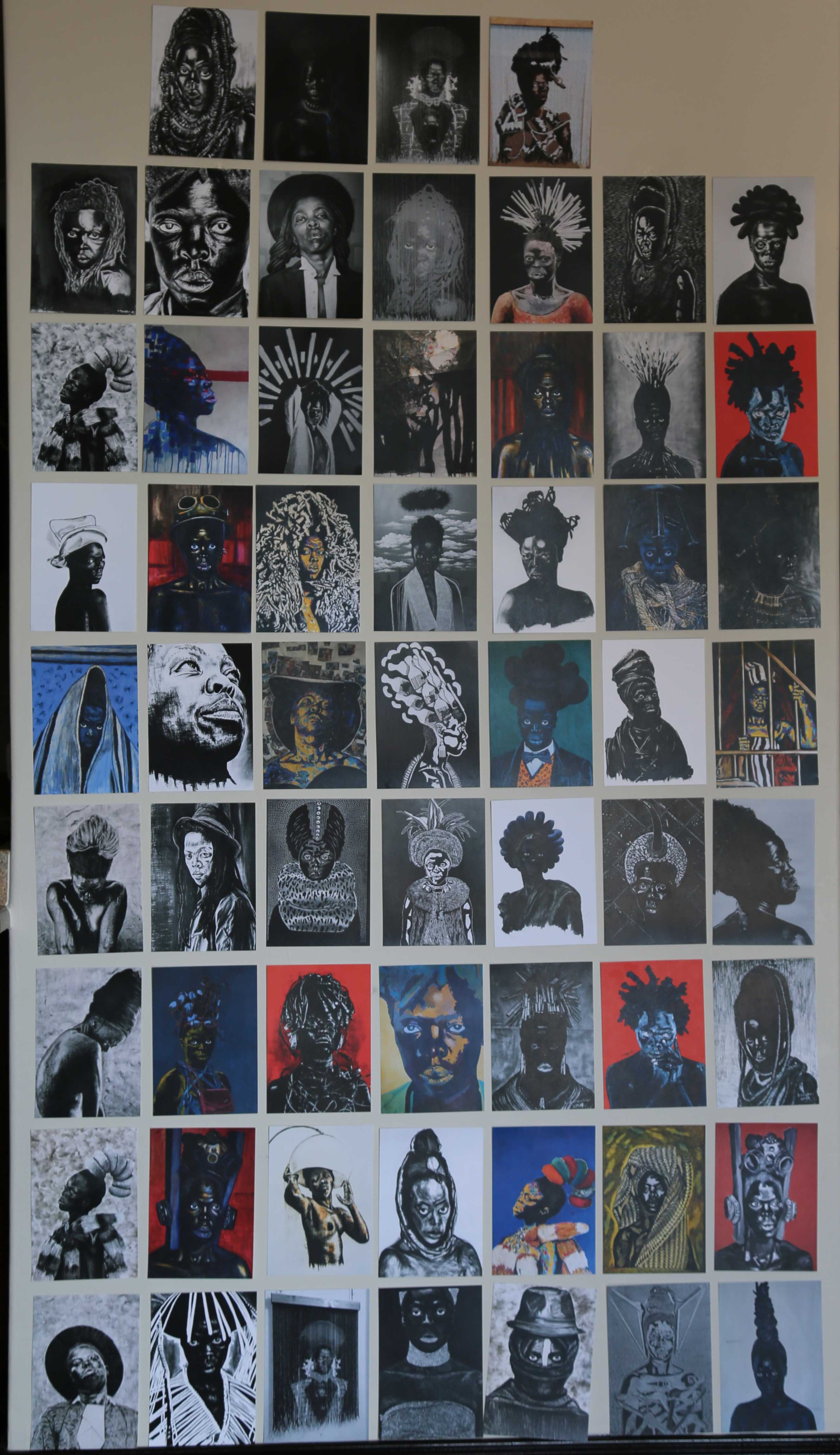

In June, Nsindane’s grade 10 art students journeyed to the Ikhono LaseNatali art exhibition at The Kwazulu Natal Society of the Arts (KZNSA). Spearheaded by world-renowned South African photographer Zanele Muholi, the exhibition was held in commemoration of the 25th year of democracy in South Africa. Ikhono Lasenatali translates into ‘talent in Natal’ and involved 25 artists from the province of Kwazulu Natal who each interpreted self-portraits from Muholi’s photo book and project, “Somnyama Ngonyama: Hail the Dark Lioness.”

“History books need to be rewritten to accommodate [black] artists who are practicing or creating in this region,” Muholi wrote in the commissioning statement for the exhibition.

For Nsindane’s students, it was the first time seeing photographs exhibited in a gallery.

“We only see photographs in newspapers and magazines,” Nsindane said. “They never thought of photography as art.”

Nsindane is determined to make a difference in her students’ lives through art. When she started teaching at Phakathi Secondary School, there was no arts education past grade 9, so she convinced the principal to develop a program for the upper grades.

“With grade 10, I teach the basic elements of art and principles of design, civilizations in art, and in grade 11, I teach the movement in art,” Nsindane said. “This is about black artists influenced by indigenous art or African art.”

The local artists commissioned to participate in the Ikhono LaseNatali exhibition used their chosen medium to interpret Muholi’s portraits. Their works included props and materials associated with African culture, including izimbadada, which are Zulu sandals, and afro combs.

The art represented democracy as well as gender violence, race, the LGBT community and other societal issues, according to Kim Kandan, a KZNSA gallery administrator.

Kandan said it is important for students who were born after 1994, in the post-apartheid era, to see this art because it allows them to better understand South Africa’s history.

“Art in South Africa in particular has always had an important role to play in struggle,” Kandan said. “We have a very long history of struggle art and resistance art. During apartheid, that was one of the main forms of the undercurrent of resisting.”

Taking her students to Muholi’s exhibition in Durban was part of Nsindane’s larger goal to introduce her students to a world of visual arts beyond their circumstances.

“The exhibition opened their minds,” Nsindane said. “Most of the learners in grade 10, it was their first time going to an art gallery. We don’t have art galleries around us, and we live far from the city, so the only art gallery they have access to is the one in town. They learned so much. They learned to work with different media.”

Phindile Madlala served as an arts educator for the exhibition and was responsible for inviting schools to the gallery, including a majority of public schools in the black townships.

Madlala echoed Nsindane’s sentiment that for students from under-resourced schools, the exhibition was an opportunity to be exposed to art, especially African art.

“Even though we are in the so-called democracy era, there are spaces that as black people, we don’t go to,” Madlala said. “All of the groups from the disadvantaged communities, it was their very first time entering a gallery space. It was their very first time even for them to travel to town.”

Of the 28 schools who participated in the program, 14 were primary schools, 12 were high schools and two were universities. Attendees ranged from grade four through university. Madlala said she invited about 100 schools but most of her outreach was met with no response.

“Maybe for political reasons, maybe because it was a black exhibition, I don’t know, we just assume,” Madlala said. “We might say 25 years of democracy, but apartheid still exists.”

Madlala said the township schools do not have a budget for transportation, so Inkanyiso Media, an organization started by Muholi, funded the transportation that brought learners to KZNSA gallery.

While students browsed the artwork, they were given workbooks to help them better understand the exhibition. Sumayya Menezes, who was the education officer at KZNSA gallery at the time of the exhibition, created two workbooks, one for primary students and one for secondary students.

In creating these workbooks, Menezes said she had accessibility in mind.

“There’s no entry point for people to actually try to find a connection with the work,” Menezes said. “With the workbooks and the materials, it’s about trying to find those entry points, trying to find a way to connect and engage and try to see where the artist is going.”

To make the works more accessible for learners in grades 4-7, Madlala translated the workbooks from English to isiZulu, the primary language taught in township grade schools.

For Madlala, inviting students to the exhibition also showed them they can make a living out of art.

“Not all of our kids will go to universities and study medicine or engineering,” Madlala said. “There are other fields we need to teach our disadvantaged learners that they can make a living out of.”

Ana Faguy ’19 contributed to this story.