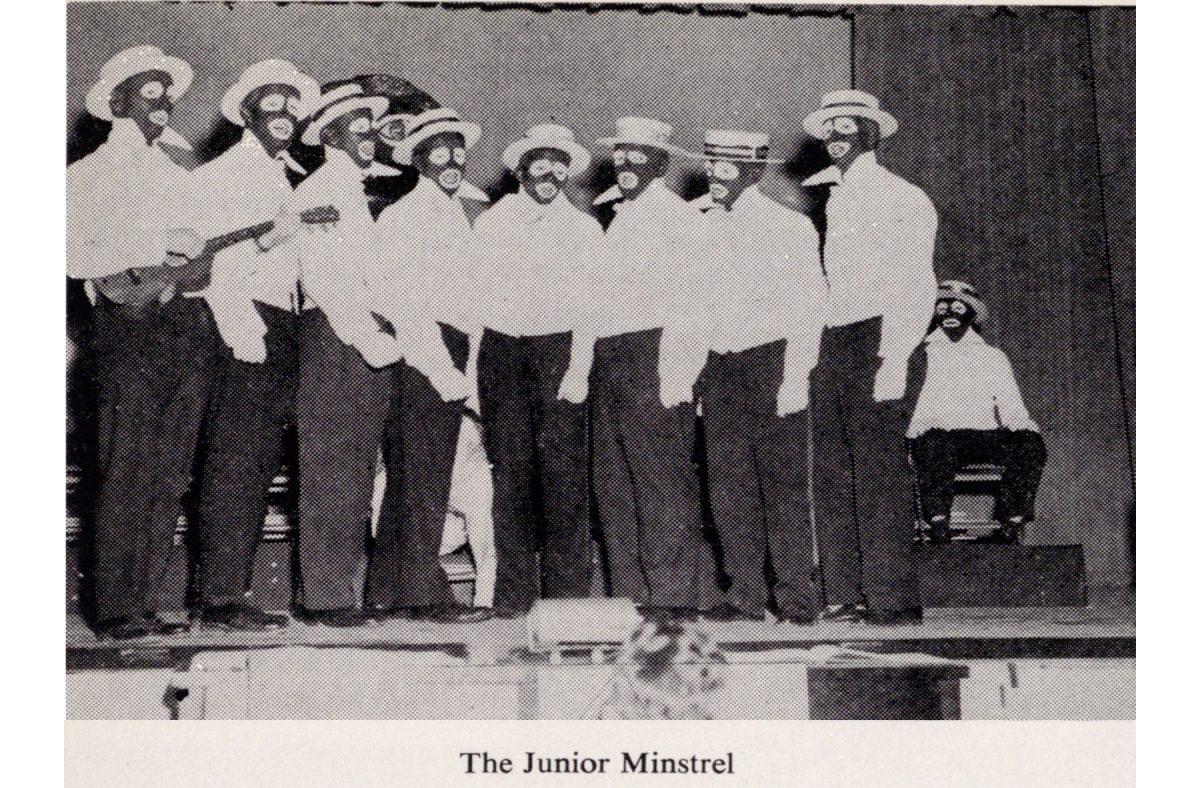

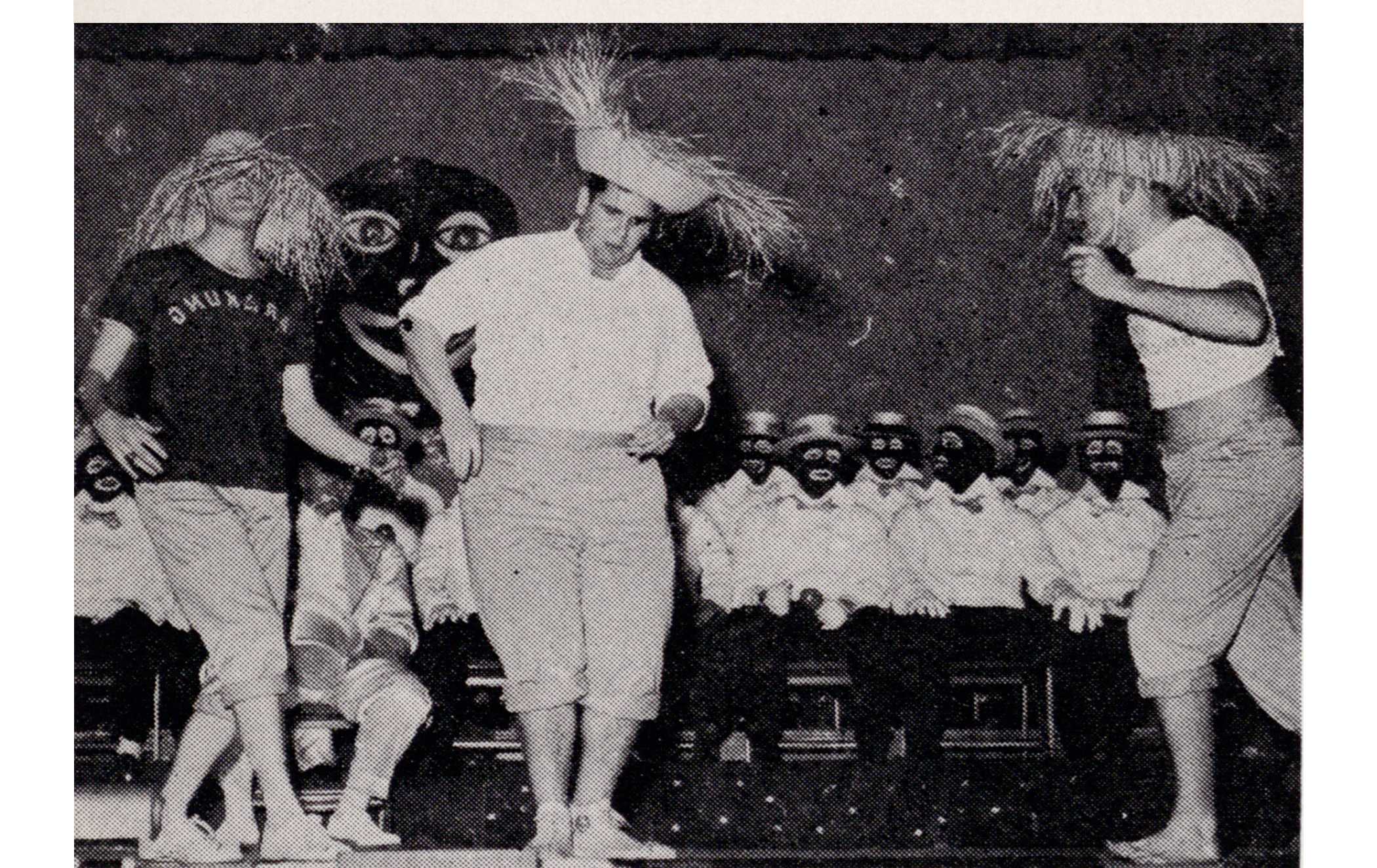

Image of blackface minstrelsy performances by the St. Joe's junior class of 1960 on page 99 of “The Greatonian” 1959 yearbook. PHOTO COURTESY OF SJU ARCHIVES AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

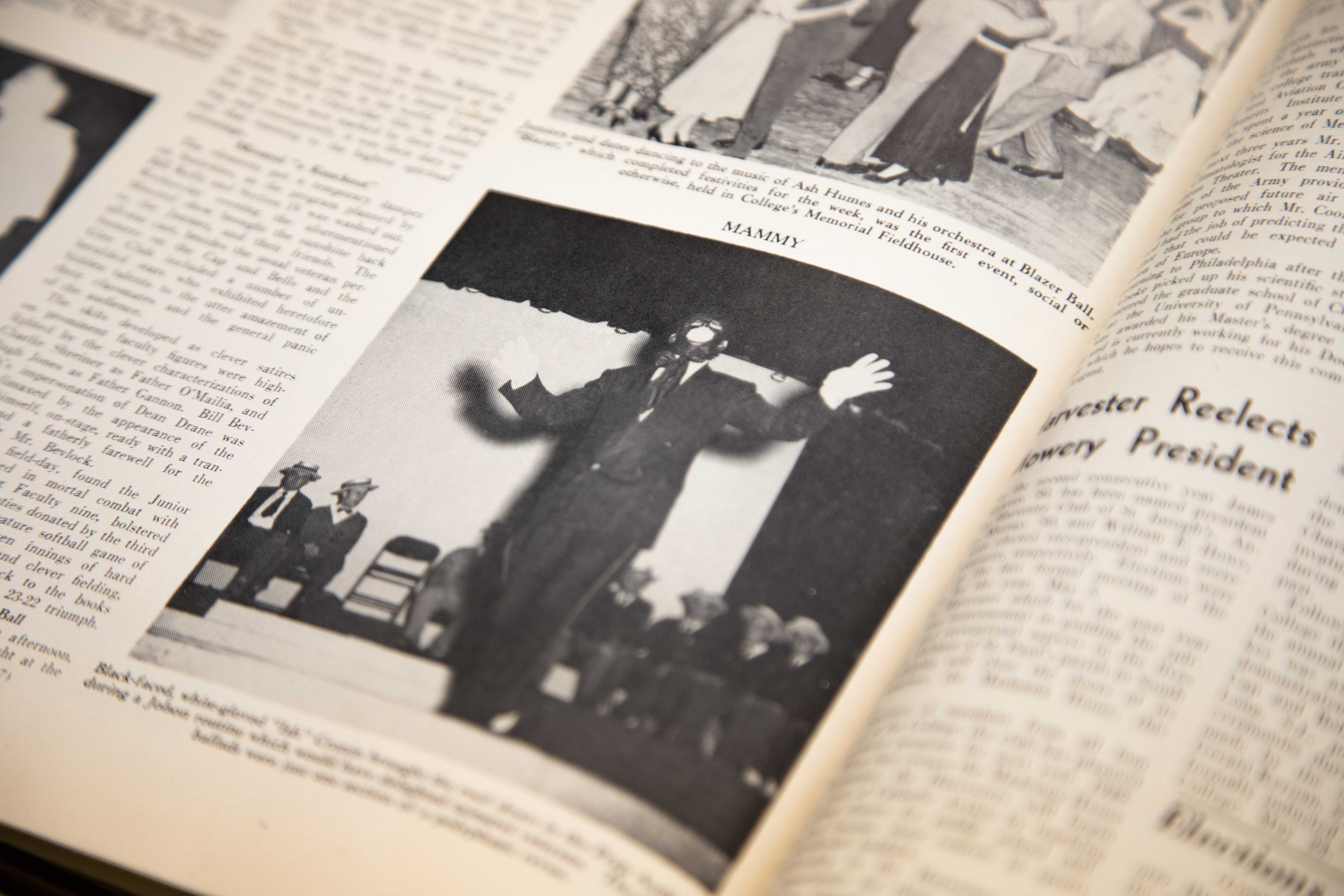

On the second page of the May 27, 1949 issue of The Hawk, a story about the university’s annual Junior Week was published, noting that the “high spot of the week and the surprise of the year was the Junior Minstrel show.” Alongside the story are photos of the week’s events, the last of which is a photo of a student performing in blackface.

The photo features Francis “Ish” Cronin ’50 performing “My Mammy” from Al Jolson’s “The Jazz Singer.” The caption under this image provides additional details: “Black-faced, white-gloved ‘Ish’ Cronin brought the roof down in the Prep Auditorium during a Jolson routine which would have delighted minstrel veterans. The blackface ballads were just one section of a polyphasic revue.”

Junior Week, an annual week-long series of events for juniors prior to their senior year, began in 1928, according to a story on page two of the June 10, 1930 issue from The Hawk’s online archive. Each year until about 1962, the event featured a minstrel show which included St. Joe’s students dressed in blackface regalia, performing on stage.

Dubbed the “Junior Minstrel Show,” these productions were performed by members of the junior class during Junior Week. A minstrel show is a type of vaudevillian performance popularized in the early 19th century in the U.S.

In these shows, primarily white performers and artists dressed in blackface and portrayed black men as the overall stupid and lazy fool, while black women were simultaneously characterized as the exoticized temptress or the matronly, hardworking “Mammy,” according to sociologist David Pilgrim, Ph.D., the founder and curator of The Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia at Ferris State University.

“When you talk about minstrels, you are really just talking about mainly a singer who is also a poet, who is also doing comedy skits and variety acts and dancing,” Pilgrim said. “It looks a little bit like the vaudeville show.”

Pilgrim, an expert on multiculturalism, diversity and race relations, is also vice president for Diversity and Inclusion at Ferris State University and collects and houses racist memorabilia for the purpose of discussing race relations and racism in the U.S.

“Blackface was not originated in the U.S.,” Pilgrim said. “People were dressing in blackface centuries before in Europe. But it became popular with a specific artist, entertainer, Tomas Rice, [who] dressed in blackface and called himself Jim Crow. He adopted the stage persona Jim Crow and had a little ditty he sang called ‘Jump Jim Crow.’”

According to the University of Southern Florida’s “History of Minstrelsy” digital collection entry on the Jim Crow caricature, while Tomas D. Rice didn’t label his own work as minstrelsy, he did inspire imitators, in particular the Virginia Minstrels, the first professional white minstrel troupe.

“Long story short, it was a success,” Pilgrim said. “People liked and were entertained [by] this black buffoon performer who was also… a little edgy.”

Pilgrim said people soon began imitating Rice, and those imitations eventually were formalized in the identifiable genre of minstrelsy.

“You start getting certain themes, certain patterns, so it developed and in conjunction with the music that accompanied it, became probably the first uniquely or distinctly American form of entertainment,” Pilgrim said.

It was out of this concretization of blackface minstrelsy as one of the first uniquely American forms of entertainment that a long history of blackface continued.

The St. Joe’s student in blackface, featured in the 1949 Hawk photograph, was performing a blackface routine attributed to Jolson from the 1927 movie “The Jazz Singer.”

Jolson was a vaudeville singer and comedian who was known for performing in blackface but also for appropriating black music and making it palatable for white audiences. His most lauded work “The Jazz Singer” heavily featured Jolson’s character doing blackface performances.

“‘The Jazz Singer’ shows us that blackface really permeated Hollywood and continued even when the minstrel show was long gone,” said Elizabeth Morgan, Ph.D., associate professor in the music, theater and film department.

Blackface, blackface minstrelsy and racist caricatures of black people continued to proliferate popular American entertainment, sometimes even being performed by black actors, dancers and comedians who had little opportunity for other work in their fields.

“You see [racist caricatures] for a really long time, and I don’t even just mean characters in blackface,” Morgan said. “African American [actors were] clearly being asked in film to perform in a way that is playing into some of the old ways, old tropes and the old racist caricatures.”

One common caricature that was performed by actors and actresses was “Mammy,” the same “Mammy” that Jolson sings about in “The Jazz Singer” and that was referenced in the university’s 1949 Junior Minstrel Show.

“The word ‘Mammy’ has to do with some of the characters in the minstrel show, [specifcally] a character like a middle-aged or older African American woman who would be called Mammy,” Morgan said.

Mammy was “portrayed as an obese, coarse, maternal figure [who] had had great love for her white ‘family,’” according to The Jim Crow Museum website.

Cronin’s performance of Jolson’s song “My Mammy” would have referenced the racially antagonistic caricature of the black woman as a maternal, happy and content slave, within a performance that itself was racially antagonistic towards black people.

Charles Reilly ’50 was a friend of Cronin, who has since died, and watched Cronin perform in 1949.

“‘Ish’ Cronin, a classmate of mine, was a multi-talented feller popular across all demos,” Reilly said. “The film ‘The Jolson Story’ was a very big hit. Blackface and singing the show-stopping songs was truly ‘in.’”

Pilgrim said blackface performances in the 1930s through 1950s were smaller scale, put on by college fraternities and sororities and featured at social parties held by businesses.

Throughout its history, St. Joe’s has been a predominantly white institution, and that factors into the acceptance of blackface on campus, according to Pilgrim.

“Whites dressing in blackface to entertain others never disappeared from private spaces, [especially in] safe white spaces,” Pilgrim said.

Morgan said the university needs to acknowledge these instances in its history in order to move forward. “In all things, if we want to have an honest conversation about the present, we really have to start by having an honest conversation about the past, where things came from,” Morgan said.

Pilgrim said it is disappointing that for many institutions, it takes a public racial incident on campus to spark such conversations. But once the conversations begin, they need to continue.

“These need to be sustained discussions,” Pilgrim said. “And when I say this it doesn’t please anybody, but I don’t think these are discussions you finish. I don’t think this is work that is ever completed, that is ever perfected.”