Students of color at St. Joe’s say they experience many types of discrimination, from microaggressions to racial slurs, inside and outside the classroom.

According to the Diversity Style Guide, an online resource for journalists that provides specific guidelines for language related to race, ethnicity, gender identity and sexual orientation, among others, microaggressions are “slights and snubs based on racial discrimination. Some are unintentional. Microaggressions can be questions or expressions about a person’s identity or abilities. They can be behaviors.”

Carla Rodriguez ’20, who identifies as Hispanic and grew up in North Philadelphia, said microaggressions were the first kinds of racial bias she experienced on campus.

“From freshman year, you hear little comments [from people] passing by,” Rodriguez said. “Even in classrooms, you hear teachers or professors commenting ‘you people’ to minority groups within classrooms.”

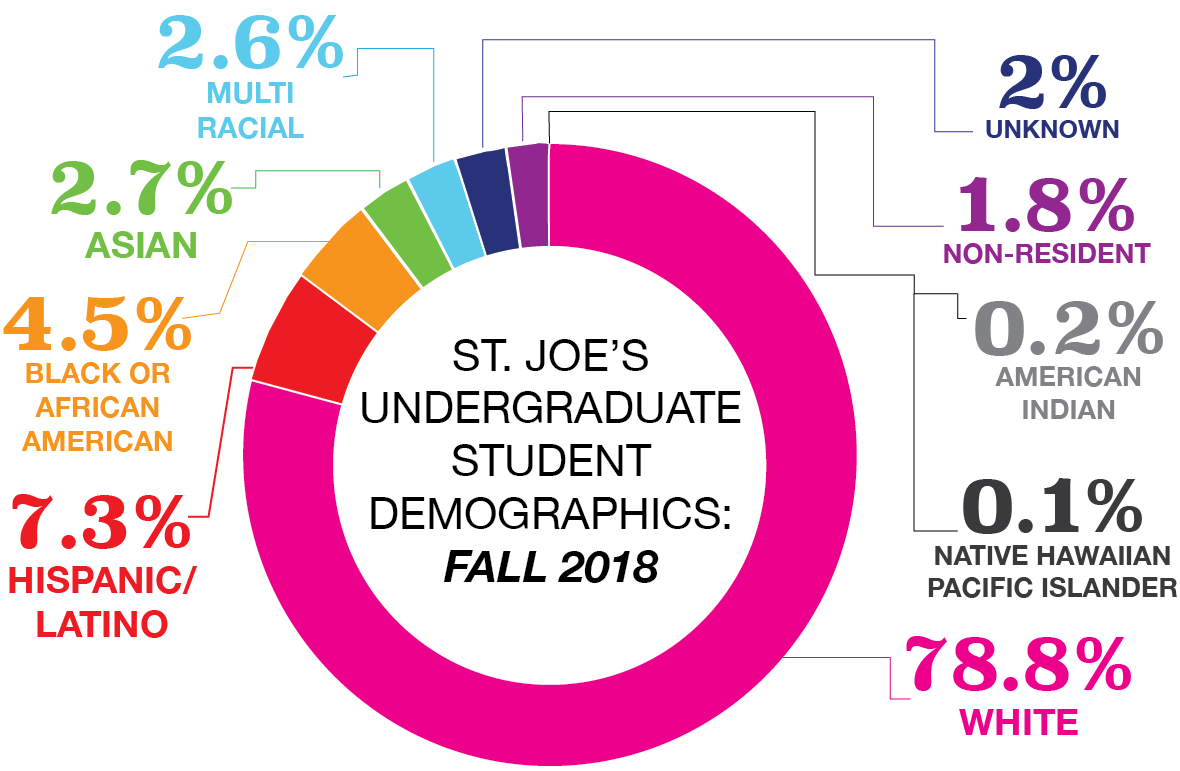

St. Joe’s is a predominantly white institution where 78.8% of undergraduate students self identify as white, according to fall 2018 data from St. Joe’s Institutional Research and Decision Support Office. A further 17.3% of undergraduates self identify as students of color, who by virtue of their low numbers stand out on a predominantly white campus.

Vilma Fermin ’20, who identifies as Latina, said speaking to her family on the phone in public often draws attention and surprise from people when they hear her speak Spanish. In fall 2018, 7.3% of St. Joe’s undergraduate students self-identified as Hispanic.

“Maybe it is not ordinary to you, but it doesn’t make it a spectacle,” said Fermin, who grew up in the Bronx borough of New York City and is a first-generation college student. “I never turn to you and go ‘Oh, my god, you can speak English.’”

The classroom can also be a difficult space for minority students. Rodriguez said she gets frustrated when, as the only Hispanic student in a class, a professor asks her to speak on behalf of all Hispanics.

“I can’t speak for everybody, and I don’t speak for everybody,” Rodriguez said. “Don’t constantly pick me out to ask me, ‘So what do you think about the entire Hispanic race?’”

Fermin said it can be tiring for students of color to constantly have to explain their racial identities and culture to others, in the classroom and elsewhere.

“Why do I have to do that?” Fermin said. “[White students] don’t do that with each other.”

Jennifer Dessus, director for Inclusion and Diversity access programs, said diversity training can allow for the creation of an atmosphere of inclusion in classrooms.

“Looking at your course or syllabus through a lens that says, ‘I’ve had [this] syllabus for years, but in what ways am I excluding a group of people?’” Dessus said.

“It’s just a new way of thinking about it.” Natalie Walker Brown, director for Student Inclusion and Diversity, said instructors should start calling racism out. “Stop saying it was inappropriate when it was racist,” Walker Brown said. “Stop saying that it was mean when it was offensive.”

Rodriguez said she once had a professor who commented on her use of English in an online discussion board for a class assignment.

“His response was, ‘Wow, your English is so good. You would never think you wouldn’t speak English,’” Rodriguez said. “I was like, ‘Who told you that I didn’t speak English?’ I don’t understand where that [comment] would come from.”

Similarly, Sara Alem ’21, who identifies as an international student and grew up in Saudi Arabia, said the professor of one of her first-year courses was frustrated with Alem’s lack of proficiency in reading and writing.

“[The professor] was annoyed by me I think because I took longer to read the exams,” Alem said. “She was like, ‘You need to go learn English before you come to university.’”

Rodriguez said even though racial discrimination occurs repeatedly in the classroom it is difficult to confront professors. “[They say] whatever they want to say because they are the professor,” Rodriguez said. “No one is going to call them out. No one can call them out.”

Rodriguez said as a student of color, she feels if racial minorities speak out against their professors, they may be stereotyped as the “loud” and “aggressive” minority.

To address students’ concerns, Dessus said faculty can work together to identify what training, dialogues and programming would best help them work on these issues.

“For all of us, what’s it about the way [we] interact, our signage, our language, what we permit to be said in our spaces that either communicates to a student or visitor that this is a place for me or this is not a place for me,” Dessus said.

Odir Dueñas ’20, a first-generation college student who identifies as Hispanic, said in order to improve diversity on campus, all members of the community have to see race issues from the perspective of minority students.

“If you are just hearing them, it is going to go in one ear and out the other,” Dueñas said. “You have to give yourself to the issue in order to solve it.”