College professors are used to navigating various complaints from students. However, a select few professors from the Erivan K. Haub School of Business have been the recipients of far more egregious complaints and behavior outside of the classroom: on the soccer field.

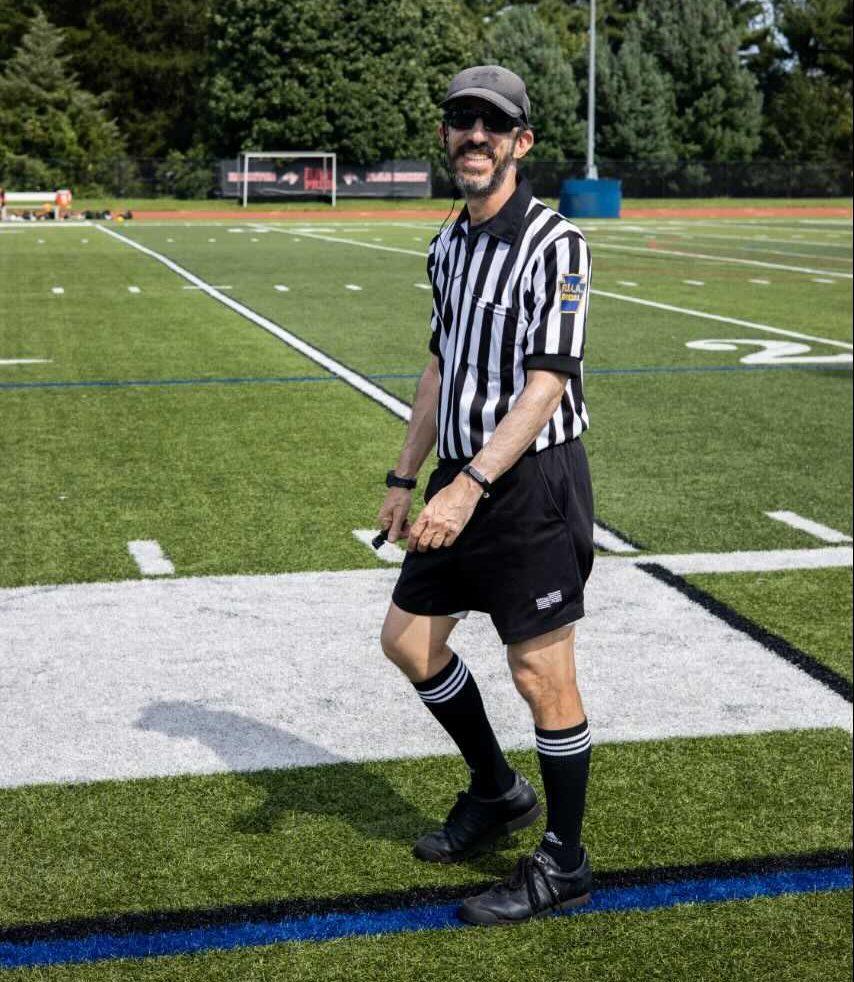

Allan, Larkin and Erkis all currently serve, or have served, as high level soccer referees. David Allan, Ph.D, professor of marketing, officiates Division I, II and III soccer and the United Soccer League (USL). Joseph Larkin, Ph.D, professor of accounting, who recently retired after 42 years as a referee, also officiated all three levels of collegiate soccer, including games with Alexi Lalas, longtime U.S. men’s national team member and current soccer commentator, when he played at Rutgers University. He also officiated Philadelphia KiXX games in the Major Indoor Soccer League (MISL). Todd Erkis, visiting professor of finance, officiates high school, young adult and youth travel club games. Erkis and Allan have worked on the same games together. According to Erkis, there are similarities between being a college professor and being a referee, such as trying to help young people navigate through adversity.

There are also a few differences.

“When I’m in the classroom, I don’t have students critiquing everything that I do,” Erkis said. “I don’t have people outside of the classroom yelling at me and calling me names.”

With a high level of competition comes a high level of scrutiny for referees. Larkin said that he’s been verbally assaulted a “fair amount.” In a few instances, the assaults turned physical.

“I threw a kid out at Holy Family University for foul language,” Larkin said. “They sent him to the van in the parking lot and after the game he starts running on the field to assault me. They caught him. He had to write me a letter of apology. I had a high school kid smack me on my forehead because he didn’t like the call.”

According to Erkis, the abuse that referees endure is still prevalent at levels in which the result of the match should be inconsequential.

“A couple of years ago I was doing an [under] eight [years-old] game,” Erkis said. “It was on a smaller field, almost like a little hockey rink type field because they’re kids. All the parents were circling the field and they were screaming at me the entire way.”

The incident made Erkis question why he devotes time to refereeing and also made him feel sad about the state of society, especially regarding how children are expected to play so competitively.

“I’m this guy who’s out there trying to make sure that their kids have fun and nobody gets hurt, and they’re screaming and yelling because a kid might have accidentally touched the ball with their hand and they want me to yellow card them,” Erkis said.

When pressed with these emotionally charged incidents, Larkin said referees have to have thick skin.

“If somebody yells at you or curses at you and tells you that you suck, you have to be objective,” Larkin said. “You can’t want to get back at them.”

Allan said that he tries to block things out by going to a different mental state as the “noise” around him escalates.

“The more chaos that goes on, the calmer I can be in my own little bubble,” Allan said. “I don’t hear a lot of it unless it affects a player or the game itself.”

Erkis said that for one bad experience, he has plenty of good ones. Erkis continues to referee because he loves the game of soccer, and enjoys the camaraderie amongst the referees and the mental challenge that officiating provides for him.

“In a well-played competitive game when you’re on the field getting some exercise on a beautiful day–I love that,” Erkis said.

Like Erkis, Allan continues to referee because of his passion for the game. According to Allan, the best referees realize, amid the dynamics on the benches or among the spectators, their number one priority should be what’s happening on the field.

“Every single player wants to win every single match. You can’t take one minute or one game off as a referee,” Allan said. “There’s no such thing as a friendly match.”