Jose Antonio Vargas, a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist, filmmaker and a leading national voice on immigration in the U.S., visited St. Joe’s campus on March 31 through the SJU Reads early arrival program to discuss his work and memoir, “Dear America: Notes of an Undocumented Citizen.”

The Hawk sat down with Vargas before his lecture to discuss his work as a journalist and life as an undocumented immigrant.

The Hawk: You wrote in your 2011 essay for the New York Times that a high school English teacher of yours introduced you to journalism and that writing stories “validated your presence” in America. Can you tell us more about what drew you to journalism?

Vargas: I was really turned on by the fact that my job was to talk to people and try to understand where they’re coming from, and I think it was a great way to get to know the country. It was a great way to be exposed to the reality that there isn’t one America. James Baldwin calls it these “yet to be United States.” The country is not really united, I think, because we just want to get along. We pretend like it is. So from the very beginning, I think I was attracted to the fact that I could get to know so many versions of America.

The Hawk: You mentioned Baldwin. In your 2011 essay, you wrote that he is one of your biggest literary influences. Why?

Vargas: My first time in Philadelphia was when I was an intern at the Philadelphia Daily News in 2001 for 12 weeks. There’s a bookstore, Giovanni’s Room, in Center City, and that was when I really studied [Baldwin’s] work. I’d heard of him, but I didn’t read everything. In California, where I’m from, everyone is Mexican, Vietnamese, Filipino, right? A minority majority place. I got here [Philadelphia] in 2001. It was Black or white. I remember once having to explain to people what Filipino was. I was so fascinated as a non-white, non-Black person about the Black and white binary. I’m working on a book now and the epigraph of my book is Baldwin saying, “I’m only Black if you think you’re white.” So, if you’re not Black or white, where do you go? The book is going to answer that question. I consider [Baldwin] like a passport. I don’t have a valid passport, but Baldwin is like a passport card, Toni Morrison is my green card, and then Maya Angelou is a really nice lavender candle.

The Hawk: What was your experience like both as an undocumented immigrant and a journalist while you were working here in Philadelphia?

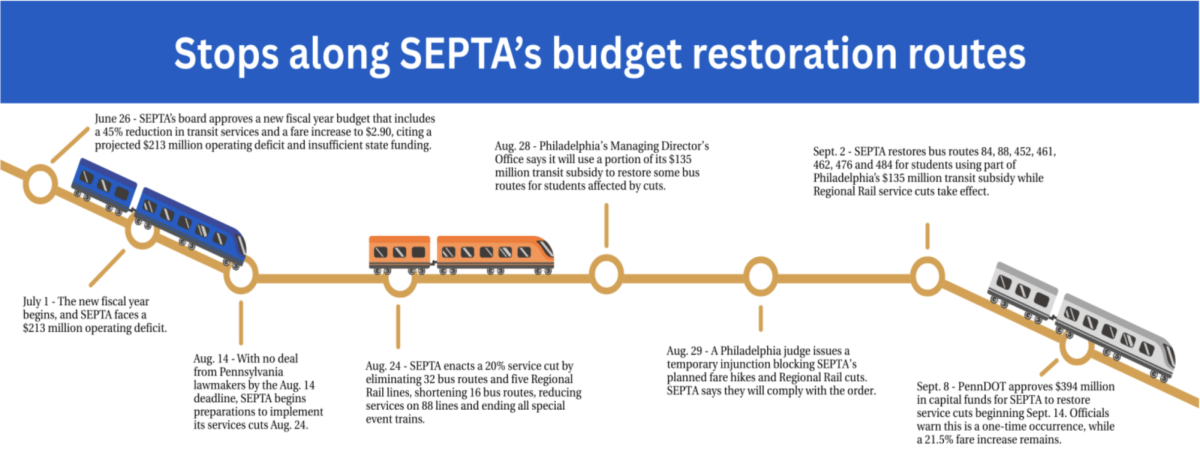

Vargas: I lied to get that internship because you needed a driver’s license, and I told them that I had one and I didn’t because I really wanted the internship. When I got here, they assigned me to homicides. Just imagine an undocumented Filipino with no car getting around Philadelphia. I got to know SEPTA really well back then, and then I hitchhiked a lot. So it was really exciting but terrifying because of the undocumented part.

The Hawk: Your nonprofit “Define American” seeks to humanize U.S. immigration and that conversation. For you, what is the most powerful thing storytelling can give through your work as an activist?

Vargas: I came out of the closet as a gay man when I was 18. It was at the height of seeing more LGBTQ representation in media, particularly television and film. I’m looking at that movement and comparing it to immigrants. And so that’s been a model for us [Define American]. How do we change and shift the narrative? Now, for the most part, it is culturally unacceptable to be homophobic, yet it’s totally culturally acceptable to be anti-immigrant. They may even elect the president for it. What we do at Define American is make it culturally unacceptable to be anti-immigrant, and we do that through stories.

The Hawk: On the same note, it is culturally unacceptable to be homophobic and yet laws like the “Don’t Say Gay” bill in Florida are still being passed. How does your work as a writer and an immigrant writer contribute to that narrative and fighting those injustices?

Vargas: Our lives intersect. I remember when I first started doing this work, there was a Filipino-American priest in New Jersey who wanted to do a big sermon on

“Dreamers” and invited me, but then said, “but we can’t talk about the homosexual part.” And I was like, am I supposed to extricate the gay thing? How would you do that? I come in full. So when people talk about intersectionality, to me, it’s like people should come in full.

The Hawk: When speaking, especially to a crowd like tonight’s that is filled with college-age students, what are some of the biggest things you hope those young people take away from your talks?

Vargas: Every major movement that’s happened in this country has been led by young people. I just hope [they question] “what does deep listening look like?” I think society and culture at large requires deep listening. And more directly, I think it’s active participation.