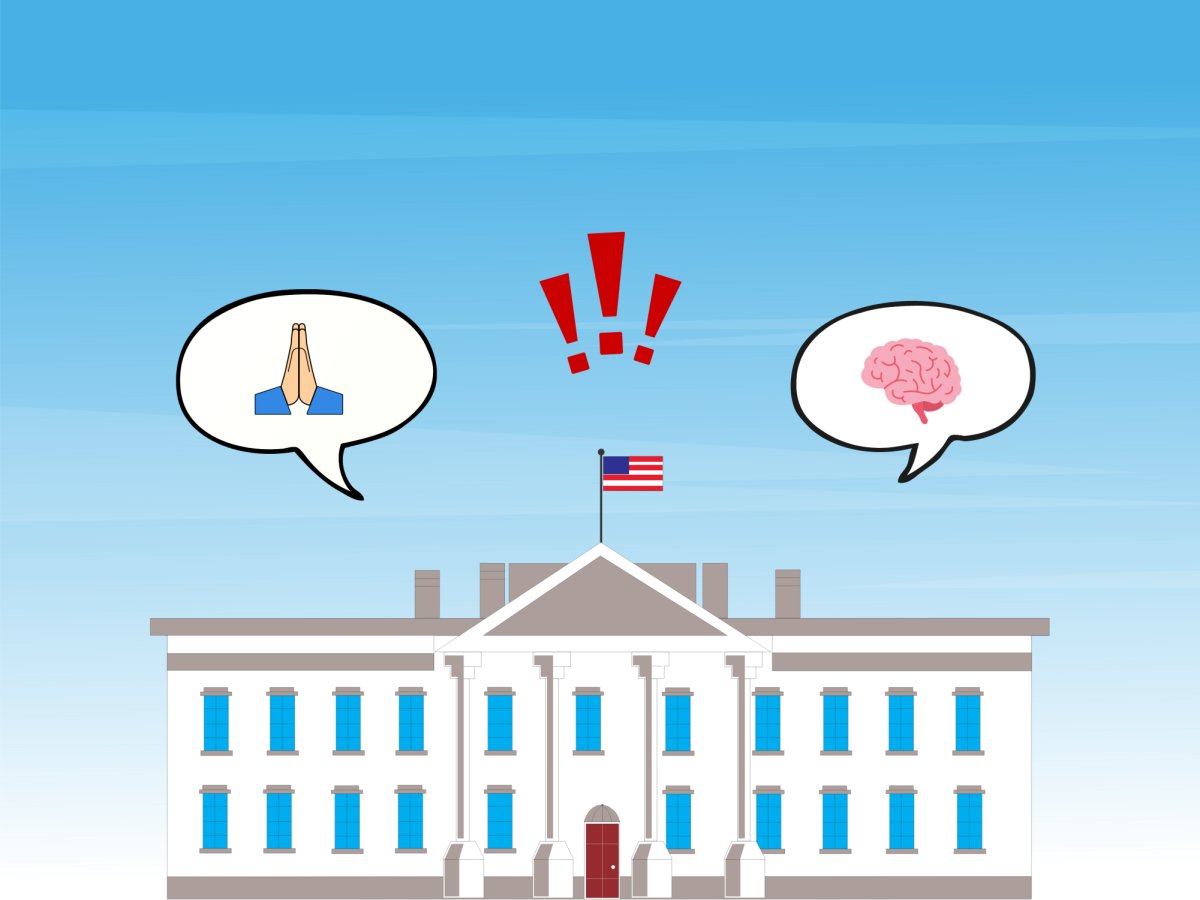

In May 2014, Pope Francis, the first Jesuit pontiff, traveled on an “apostolic pilgrimage” to the Middle East. As the first Jesuit pope, who visited Hawk Hill in 2015, his perspectives are perhaps especially instructive for us at Saint Joseph’s University. The present crises are incredibly polarizing, but Francis’ observations provide both a historically informed and global vantage point that is much needed.

To Palestinian leaders, he stated that “the time has come for everyone to find the courage… to forge a peace which rests on the acknowledgment by all of the right of two States to exist and to live in peace and security within internationally recognized borders.” He prayed at the so-called “security barrier” between the West Bank and Israel, expressing his dismay at the “unacceptable” divisions it concretizes.

In Israel, Francis laid a wreath at the tomb of Theodor Herzl, the 19th-century father of the Zionist movement whose purpose was to establish a modern nation-state in the biblical homeland of the Jewish people. This gesture anticipated the pope’s words in 2015 that “the State of Israel has every right to exist in safety and prosperity.”

The legal principle at work in both actions is the right of peoples to constitute themselves as a state, in this case, Palestinians and Israelis, which is known as national self-determination. This is why Francis has repeatedly insisted upon the necessity of the “two-state solution.”

In the years since 2014, Francis has urged the necessity of a broader regional peace. He has, for instance, lamented the deaths of about 500,000 Syrians in civil conflict since 2011, the 6.6 million refugees who have fled that country and the additional 6.7 million internally displaced persons. The pope regards the current Israel-Hamas war as part of a much larger set of crises that also encompass the invasion of Ukraine by Russia and the terrible violence in Sudan and Myanmar. Francis sees all this as “‘a sort of piecemeal world war,’ with serious consequences on the lives of many populations.”

Along with every thoughtful person, Pope Francis agonizes about “the right of those who are attacked to defend themselves,” while simultaneously being “very concerned about the total siege under which the Palestinians are living in Gaza, where there have also been many innocent victims.” He has repeatedly urged the release of the hostages taken by Hamas (a proxy of Iran), while also insisting that “The Middle East does not need war, but peace, a peace built on justice, dialogue and the courage of fraternity.” Moreover, he “unequivocally condemn[s] … the terrible increase in attacks against Jews around the world,” as well as widespread Islamophobia.

Like his immediate predecessors, Pope Francis hopes that all Catholics will be agents of dialogue wherever they may live. This means avoiding sloganeering and futile “quick fixes.” It means cultivating empathy for the conflicting narratives of pain throughout the Middle East, as well as for the misery of those in other countries who suffer loss and fear for loved ones there. It means, in his words, that “we must commit ourselves to [the] path of friendship, solidarity and cooperation in seeking ways to repair a destroyed world, working together in every part of the world… to see in the face of every person the image of God, in which we were created.”

Philip A. Cunningham, Ph.D., is the director of the Institute for Jewish-Catholic Relations and a professor of theology and religious studies.