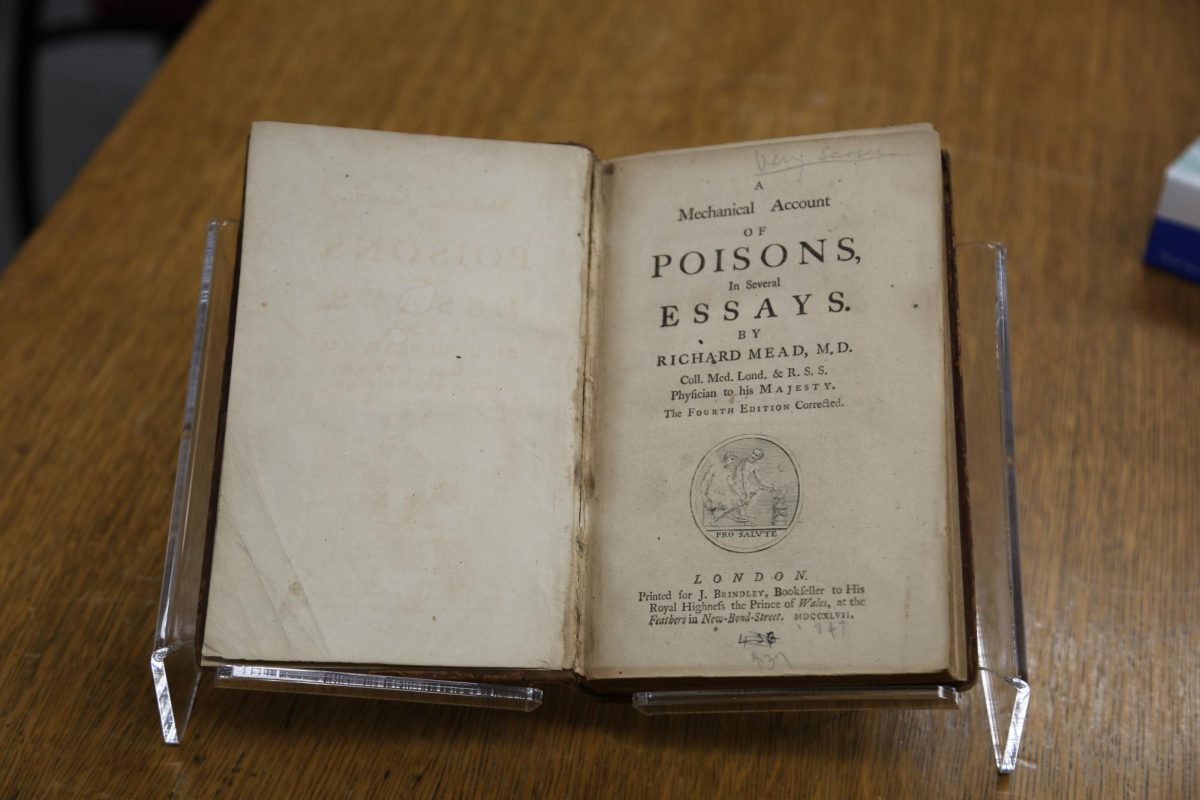

In 1702 prominent English physician Dr. Richard Mead published “A Mechanical Account of Poisons in Several Essays,” a book that laid the groundwork for the future of the field of toxicology.

“A Mechanical Account of Poisons in Several Essays” contributed to the Enlightenment era’s growing knowledge and interest in medicine.

The copy currently held in the Special Collections of the St. Joe’s Archives is the fourth edition, printed in 1747. It is visibly old, with fading yellow pages that are, in some cases, falling off the spine.

In the preface to the book, Mead offers his work as a scientific anecdote to one of the intellectual poisons of his time: superstition. He promises “short Hints of Natural History, and Rude Strokes of Reasoning; which, if put together, and rightly Improved, may perhaps serve to furnish out a more tolerable SPECIMEN of the DOCTRINE of POISONS, than has yet been Published.”

After graduating from the University of Padua in 1695 with a medical degree, Mead returned to his hometown of London, where he dedicated his time to studying toxins and their effects on the human body. He specifically studied tarantulas, vipers, rabid dogs, poisonous minerals and plants, poisonous air and water, and opium. He compiled his findings into essays, which were bound together in book form.

Mead seemed particularly fascinated by snake bites, listing the symptoms that can occur after a viper “fastens either one or both its greater Teeth in any Part of the Body”: “Swelling at first Red, but afterwards Livid,” and “a Quick, tho’ Low, and sometimes Interrupted Pulse, great Sickness at the Stomach, with Bilious, Convulsive Vomitings, Cold Sweats, and sometimes Pains about the Navel; and if the Cure be not speedy, Death it self.”

Fred Gibbs, Ph.D., associate professor of history at the University of New Mexico and author of “Poison, Medicine, and Disease in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe,” said physicians like Mead were interested in whether poisons were inherently harmful or could have therapeutic value.

“That attitude (that there was no such thing as an ‘absolute’ poison) was relatively new at the time, and researchers are still today investigating the nature of venom and other known toxins to see how they could be useful in medicine,” Gibbs said.

Emma Gunuey-Marrs, assistant curator of the Marvin Samson Museum for the History of Pharmacy, located on the University City campus, said books like Mead’s likely influenced early physicians in the U.S.

“Colonial apothecaries were looking to England for a lot of their educational material,” Gunuey-Marrs said. “It’s very possible that a colonial apothecary would have been referencing this book.”

Gibbs said the fact that scientific thinking has changed so much from Mead’s time makes it challenging to compare 18th century medicine to modern medicine.

“But one thing remains true and will always be true,” Gibbs said, “scientists are always doing everything they can to understand how to have more effective treatments, no matter how weird we might think their conclusions are when looking back in time. Surely future physicians are going to look [at] what we now think of as cutting-edge medicine and wonder how we went so wrong.”

Mead’s book is part of a large collection of over 1,400 historical pharmacology books that the SJU Archives acquired in the wake of St. Joe’s 2022 merger with the University of the Sciences.