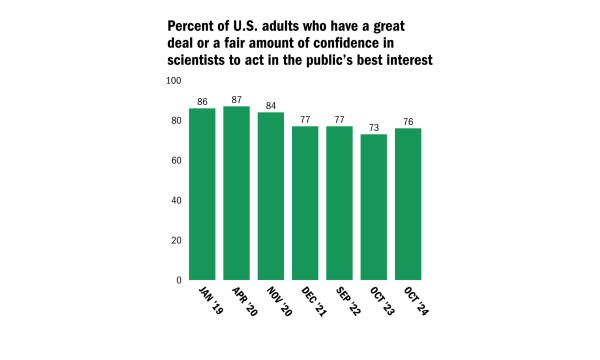

Americans’ trust in scientists has fluctuated in recent years, increasing this year for the first time since before the covid-19 pandemic, according to a Pew Research Center study.

The study, conducted in October 2024, found that 76% of Americans have either a great deal or a fair amount of confidence that scientists will act in the public’s best interest. While up from 73% in October 2023, that number is still down from 87% in April 2020.

This year’s 76% of Americans is a combination of 26% of Americans who have a great deal of confidence and 50% who have a fair amount of confidence. Meanwhile, 23% of Americans have not too much or no confidence in scientists to act in the public’s best interest.

Confidence in scientists declined throughout the entire span of the covid pandemic, and the pharmacy field has felt the effects, said Edward Foote, PharmD, professor of pharmacy and dean of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy (PCP).

“The best example is mistrust in immunization,” Foote said. “We always had an anti-vax movement, people that didn’t believe in vaccinating their children, concerns over developmental delays. During the pandemic, it just blew up, people questioning the motives of the government, of [the] pharmaceutical industry, of scientists in promoting covid vaccinations.”

The U.S. government’s handling of the pandemic sowed doubt about public health officials in many Americans, agreed Melissa Snyder, Ed.D., dean of the School of Nursing and Allied Health.

“The experience of the pandemic really shook a lot of people’s belief about our healthcare system and its ability to respond to crisis … There were many things that happened in that span of a few years that made people question whether or not the decisions people in positions of authority were making were really in the public’s best interest,” Snyder said.

Public policy

But covid is not the only reason for the public’s shifting trust in science.

Both Snyder and Foote point to another aspect of Americans’ wavering confidence: the relationship between scientists and public policy.

“The assault on science is much deeper than simply covid,” Snyder said. “It runs very deep, whether it’s through political connections or belief systems and value systems. People are questioning authority as well as the science itself.”

According to the Pew study, Americans are split on whether scientists should be involved in policymaking — 51% say they should be. But within political affiliations, a majority (64%) of Republicans oppose scientists’ involvement in policy decisions, while 67% of Democrats support it. Still, this leaves nearly a third (32%) of Democrats who also oppose it.

Foote said the “decay of the trust in science” goes beyond party lines.

“Much of [the distrust in science] is related to what’s going on in public policy, politics, leadership in this government, government in general,” Foote said. “It’s not even partisan. It’s just that we don’t trust each other.”

Science is not a certainty

Another reason for the fluctuating trust in scientists may be a misunderstanding of science itself.

Preston Moore, Ph.D., professor of chemistry and chair of chemistry and biochemistry, offered the example of a theory. To scientists, a theory is something that is not proven but matches the available evidence. To nonscientists, a theory may be something that is simply not proven. Gravity, Moore explained, is a theory — if you hold a bowling ball over your head and let go, will it hit you in the head?

“The scientists always have a small, little caveat of, ‘It may not do it,’” Moore said. “Yes, it’s going to hit you in the head. There’s no question. But, it’s still a theory, and that language disconnect causes confusion.”

When new information prompts changes or updates to current theories, it can also contribute to confusion and mistrust, said Wendy Walsh, Ph.D., clinical associate professor and chair of occupational therapy.

“People don’t like change, so they want the answer, and then they don’t want people to say, ‘Maybe’ or ‘It depends’ or ‘It could be.’ Those are like death sentences in science,” Walsh said. “But really, science is ever evolving, so if you don’t understand that, or you don’t agree with that, you may say science is not real.”

Science’s indefinite nature may make people so distrustful because theories are often presented as if they are 100% proven, partially in an attempt to simplify complex ideas, said Patrick Garrigan, Ph.D., professor and chair of psychology.

“Scientists might make some recommendations and sound overly confident because they’re simplifying, talking about something that is probabilistic as if it’s a certainty,” Garrigan said. “But anything that’s probabilistic is sometimes going to turn out to be wrong or not apply in a particular case, and then people might get suspicious.”

The impact of this lack of certainty is also evident in fields like environmental science.

“People often have a difficult time accepting things that they cannot observe directly,” said John Braverman, Ph.D., associate professor of biology and director of the Environmental Science and Sustainability Studies Program. “In my classes, I’ve drawn a parallel between accepting climate change and accepting the biological account of evolution because both of those things were happening very slowly and somewhat imperceptibly.”

Improving communication

To avoid the misunderstanding that comes with simplification, Garrigan said scientists need to more clearly communicate the probabilistic nature of their results.

“I think it would be better to be more upfront with people about the certainty of recommendations that come out of science,” Garrigan said. “Then we would also have to be clear that you don’t have to be 100% certain in order to make a decision.”

Good communication — or lack thereof — is yet another potential reason for the public’s lack of trust in scientists. The Pew study found that 52% of Americans believe research scientists are not good communicators.

Many of the faculty members The Hawk spoke to agreed more should be done to enhance communication and the sharing of information between scientists and the American public.

Peter Clark, S.J., Ph.D., professor of theology and religious studies and director of the Institute of Clinical Bioethics (ICB), is building communication and transparency into the ICB’s Health Promoter Programs, which provide healthcare for underserved populations in Philadelphia. Clark emphasized the importance of “informed consent” — telling people exactly what is being done to them and why, through each step of a procedure.

“I want [the students] to explain very clearly to the patients, ‘We’re putting alcohol to wipe off any type of infection that might be there. We’re now going to prick your finger on the side. Why on the side, not in the middle? Because it’s a greater flow of blood on the side.’ I want them to know exactly what they’re doing and what’s going to happen to them,” Clark said.

Clark also added that medical professionals should take advantage of social media to better inform the public, especially to combat anti-vaccine sentiments, which were prominent on social media even before covid.

In fact, educating all people on the scientific method, not just science-focused people, can help the public better understand science, Moore said.

“The two-way street of people taking the courses in science, whether they’re scientists or not, just understanding that method, and then also the scientists engaging in the public, could decrease the miscommunication that happens,” Moore said.

Ultimately, the responsibility falls both on the American public to make sure they are consulting reliable sources and on scientists to improve how they present information to the public, Garrigan said, and he hopes confidence in scientists will continue to increase moving forward.

“[Trust in science] wasn’t just going down. It was varying over time,” Garrigan said. “Hopefully that means that we’re at a low point now, but we’re heading into a more trustworthy future.”