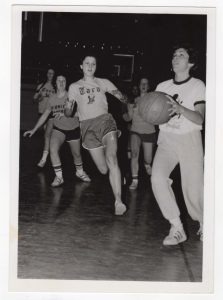

Kathy Garvin ’75 recalled a sign on a St. Joe’s campus bathroom with the letters “WO” taped in front of the word “men.”

Garvin, who enrolled at St. Joe’s in 1971, one year after the university first opened its doors to women, played on the first varsity women’s basketball team at the school. She has other memories of the bumpy welcome that women, especially athletes, experienced in those early days of coeducation.

A commuter, Garvin remembered the late-night drives on Roosevelt Boulevard along with her teammate Cathy Cosgrove ’75, the two of them exhausted. St. Joe’s men’s varsity, junior varsity and first-year teams took priority when it came to practice space and times. So, Garvin and Cosgrove often drove home as late as 10 p.m., their team only getting one to two late practice slots a week.

“We didn’t really get much priority,” Cosgrove said.

Over 50 years later, women’s college basketball is in a transformational period nationally. A viral video of women’s weight rooms at the NCAA Tournament in 2021 exposed the lack of equipment and resources offered to the teams, sparking conversations about equity. The NCAA added $6.1 million to the women’s tournament budget the following year in 2022. That same year, the term “March Madness” was expanded to apply to the women’s tournament as well.

In 2024, the women’s NCAA title game drew 18.7 million viewers, nearly four million more than the men’s championship. 2025 marks the first tournament for which women’s teams will be paid for playing in the tournament, operating under the same format the men’s teams have for years. The teams will receive payment for this year’s tournament starting in 2026.

The NCAA did not start governing women’s sports until 1981, so in 1974, the year Kathy Langley ’78 joined the St. Joe’s team, the national women’s basketball scene was far different than it is today. And life at St. Joe’s for the women players remained a challenge throughout those early decades. Oftentimes, the St. Joe’s men’s teams would go over their allotted times, leaving the women’s team no choice but to wait.

“We were definitely third-class citizens,” Langley said. “[The men] weren’t against us. They just weren’t doing anything to help us.”

Women’s basketball officially became a varsity sport for the 1973-74 season, after being designated as a club sport starting in 1970. During that time, most of the club members were Evening College students. Their coaches at the time were two male students. When it became a varsity program, Ellen Ryan became the coach, and night students were no longer allowed to participate.

“There was nothing that really made it seem all that different,” Cosgrove said. “We still didn’t get much in the way of transportation and things like that. I think we were still driving ourselves to half the games. Every now and then, I think we got some kind of a minivan or something to take us to games.”

The uniforms were T-shirts with their names and numbers on the back. Langley compared their lockers in the locker room to those found in a high school hallway, noting that none of them ever used the showers there. But still, they wanted to play.

“If you weren’t serious, you weren’t playing because there was nothing to be gained from it,” Langley said. “We weren’t getting sneakers. We weren’t going on airplane flights anywhere. We were playing because we love to play basketball, because we love basketball.”

Still, their love of the game didn’t always fully block out the outside noise. Garvin still remembers an article in the Philadelphia Bulletin, a daily evening newspaper, that discussed a teammate’s “supple legs” during her foul shots.

“I wrote to the [Bulletin] and said, ‘You never say, “Dave Schultz’s broad shoulders.” How dare you talk about someone’s legs?’” Garvin said.

When local media coverage veered away from physical appearance and toward the game, there still wasn’t much of it. Usually, the extent of their coverage was a brief mention in the “People in Sports” column by Herm Rogul, a sportswriter for the Bulletin.

“It would be all little blurbs about all the games that happened last night,” Garvin said. “He used to do it every day, and that was the biggest coverage that we had. That’s how we would get in the paper most of the time when we were playing.”

Attendance was a separate issue. Cosgrove said most of the fans watching them play came from their immediate circle of family and friends, other than when the Hawks played an occasional game against the then nationally recognized Immaculata women’s team. In comparison to the “bedlam” of a men’s game at The Palestra, Cosgrove said the women never had anything similar.

“We were pretty much doing it for ourselves,” Cosgrove said.

What they didn’t know then was that their struggles and experiences were building the legacy of St. Joe’s women’s basketball.

“They paved the way,” said current basketball head coach Cindy Griffin ’91, MBA ’93. “They did so much with so little, whether it be lack of scholarships, transportation, equipment, but they just love basketball. And I think that’s the theme that has been carried over from [the] program, from years to years. When you play at St. Joe’s, you have a deep love for basketball.”

By the time Mary Sue Simon ’78 was a sophomore, scholarships were offered, thanks to Title IX, which passed in 1972 as a federal law that prohibits gender-based discrimination in any educational program or activity.

In fall 1974, Theresa Grentz, a former Immaculata women’s basketball player, was hired as the head coach for St. Joe’s 1975 women’s basketball season. It was during these years, the latter half of Simon’s four years with the program, that things truly began to change.

“Obviously, the coaches pushed for everything, uniforms, sneakers, we pretty much did a bus everywhere,” Simon said. “We were lucky to have some good athletes and a good team, but [the coaches] really were behind us, pushing to get the things that we needed to succeed.”

And they did succeed, competing in the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women women’s basketball tournament in 1977, a national tournament with 16 teams at the time. It was an early variation of what the NCAA Tournament is today. Simon credits the team’s success with helping get the word out about the program a few years after it was established. She also recalled articles each weekend in the Daily News or the Philadelphia Inquirer on the team and reporters consistently at their games.

“For example, St. Joe’s women playing Immaculata would have been a strong interest in this area,” Simon said. “So, it would probably sell out. If we were at the field house, the attendance was pretty strong.”

All these years later, even with some significant changes within the NCAA, Garvin doesn’t think women are being treated as equals in college basketball yet.

“I still don’t think it’s changed enough. I find that very irritating,” Garvin said. “It’s just got to get better.”

Attendance at women’s games still lags behind men. Men’s basketball also dominates most media coverage.

But the women who played in St. Joe’s early years continue to show up because they still love the game, and they want to support today’s players. Cosgrove and Langley are season ticket holders. The two of them, along with Garvin and Simon, attend alumni games, including in 2024 when St. Joe’s women’s basketball was honored during a game for its 50th anniversary.

Griffin said she and the team acknowledge what, and who, it took to get them where they are today.

“We’re made from our history. You always look back and you see the accomplishments of the teams before us. … Learning those life lessons have been very valuable for me and for our present-day program,” Griffin said.

This article is the third story in a series focused on women in college sports media and the issues they are facing.