GRAPHICS: CARA HALLIGAN ’25/THE HAWK

As colleges and universities across the country grapple with the consequences of federal research funding freezes, cuts and cancellations, the future of funding at St. Joe’s remains unclear.

St. Joe’s currently manages about $25 million in active funding and brings in an average of $8 million in new funds a year, said Tom Kaeo, director of the Office of Research Services. For research specifically, St. Joe’s has $19 million in active research funding, according to St. Joe’s website.

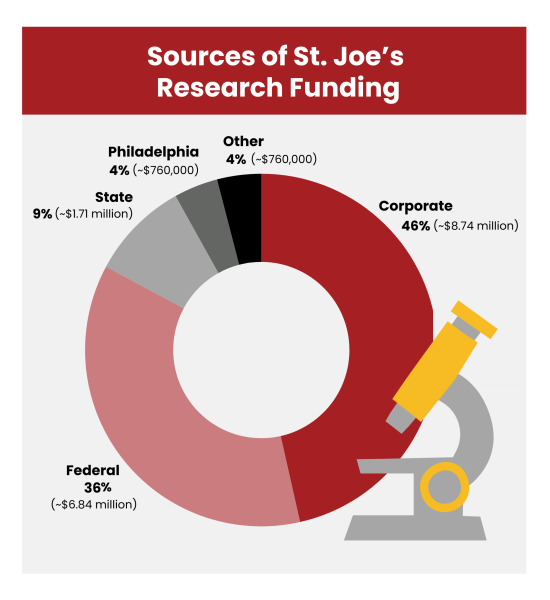

Much of this research funding comes from private corporations, the state or the municipality, Kaeo said. But 36% comes from the federal government, according to a February message from Jean McGivney-Burelle, Ph.D., provost and senior vice president of academic affairs, announcing that St. Joe’s was designated a Research 2 institution by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

This federally-funded research is at risk as President Donald Trump’s administration continues to take action to cut and restrict federal funding for colleges and universities.

By the numbers

The National Institutes of Health, one of many federal departments that provides research funding to colleges and universities, announced Feb. 7 that it will cap indirect cost rates for all its grants at 15%, and the Department of Energy followed suit April 11. While both reductions have been blocked by judges, many universities that rely heavily on federal funding would face staggering losses should the NIH and DOE move forward with the rate restriction.

Indirect costs, also called overhead or facilities and administrative costs, cover costs not directly associated with research, like utilities, equipment and personnel. While direct costs go toward the researchers and their work, indirect costs cannot be linked to one specific project and go toward the institution (rather than the researcher) to pay for the research infrastructure.

Typically, indirect cost rates are negotiated per institution. St. Joe’s currently has a negotiated rate of 45%, meaning the funding it receives for indirect costs represents 45% of its total federal funding, Kaeo said. If the NIH indirect cost rate does drop to 15%, St. Joe’s would lose nearly $90,000, according to an analysis of 2024 NIH funding data. Compared to other research schools, though, St. Joe’s will not be hit as hard, Kaeo said.

“Fortunately, for us, if we went down to 15%, it would not impact us as much as it would a larger R1 university, like University of Penn or Temple or Drexel,” Kaeo said. “We would lose about 15-20% of our indirect cost recovery, and that is mainly because we have a lot of private and corporate contracts that really help make up that difference.”

St. Joe’s receives research funding from corporate (46%), federal (36%), state (9%), Philadelphia (4%) and other (4%) sources, according to McGivney’s announcement. This amounts to roughly $8.74 million from corporate funds, $6.84 million from federal, $1.71 million from state, $760,000 from Philadelphia and $760,000 from other funds.

Institutions like the University of Pennsylvania, which rely more heavily on federal funding, are facing much harsher circumstances. The Daily Pennsylvanian reported in March that Penn received over $1 billion in federal funding in fiscal year 2024.

Penn’s negotiated indirect cost rate is 62.5%, but this only covers half of its indirect costs, according to a Feb. 11 statement from Penn President Dr. J. Larry Jameson, Ph.D. The dramatic drop to 15% would result in a loss of at least $240 million in funding at a time when Penn is also facing the termination of multiple federal research grants, Jameson wrote.

Wendy Walsh, Ph.D., clinical associate professor and chair of occupational therapy, is a co-investigator on a multi-million dollar Penn research grant. Walsh said she negotiated to receive a subaward of about $25,000, which goes partially to her and partially to St. Joe’s, meaning if the Penn grant was terminated, so too would be the St. Joe’s subaward.

While Walsh does not believe her project is at risk due to how far along it is, she said the terminations are an “ever-present, looming concern” for researchers.

Diversity, equity and inclusion

While the indirect costs rate cap was motivated by the federal government’s goal of cutting costs wherever possible, other research funding is being terminated or frozen at institutions that have diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives — initiatives Trump called “discriminatory and illegal” in a Jan. 21 executive order.

The Trump administration said it would cut $175 million in funding to Penn due to the university allowing a transgender woman to swim for the women’s swim team in 2022. Harvard University is also facing funding freezes of $2.2 billion due to their refusal to eliminate their DEI policies, and the NIH recently announced bans on new grants to institutions with DEI initiatives.

But some grants still have components related to DEI that require researchers to explain how they will include underrepresented minorities in their field, leftover from the administration of former President Joe Biden, said Preston Moore, Ph.D., professor and chair of chemistry.

“You still have to have a section, according to the request for proposals, that specifically states how you will recruit and include underrepresented minorities in your grant. That, I assume will change, but currently it hasn’t yet,” Moore said.

Stephen Moelter, Ph.D., associate professor of psychology and co-director of the neuroscience program, said diversity components in grants can also be an “important scientific question.” Some people-based projects may necessitate a sample population of “all the same kind of people,” but others may need “many people from different groups,” depending on the goals of a particular project.

“It’s a little unclear, moving forward, what the administration would expect you to put in a scientific box, mostly just for the methodology,” Moelter said. “The method or the design of your research depends on, especially with human subjects, talking about the characteristics of those subjects so that you know how well your study finding is generalized to other people.”

Small number, large impact

Although St. Joe’s immediate potential losses from federal funding cuts are small in comparison to research giants like Penn, cuts will still have a significant impact on the group that benefits from federal funding perhaps more than anyone else: students.

“We’re training the scientists to be graduate students at those places [more research-heavy institutions], so even though it doesn’t directly impact us, it does have indirect effects,” said Julia Lee-Soety, Ph.D., associate professor of biology and co-director of the center for undergraduate research. “We’re not going to be able to train students that will go on and become graduate students at those research-heavy institutions.”

Losses in funding also means the students do not get the opportunity for real research experience, which, in turn, could discourage students from pursuing the sciences in the first place, Lee-Soety said.

“A lot of researchers in the natural sciences rely on research money to ask scientific questions and to train students, to train the next generation of scientists,” Lee-Soety said. “Not having those research funds not only harms their own research agenda, but it’s going to have long, long-term effects down the road because students are not going to be wanting to do science if they can’t find a lab that’s going to support them.”

Moore said the bulk of research funding in chemistry goes toward students, for things like attending conferences and working over the summer to support faculty on their research projects. Without the students, and without the funding to hire them, “the research doesn’t get done,” Moore said.

For Moelter, even if St. Joe’s is “insulated” from the worst of the funding cuts, the impact on student experience is significant.

“Even if it’s a small number of students who are affected … that’s a huge impact to a small institution that really relies on a personalized touch and a personalized experience,” Moelter said.

Looking to the future

Federal funding can be key to supporting projects that serve the advancement of science, wrote Catalina Arango Pinedo, Ph.D., associate professor of biology and director of the McNulty Scholars Program, in an email to The Hawk. Often, institutions do not have the money to fund these projects themselves, and private institutions may not be interested in funding them — so when federal funding is lost, even at smaller research institutions like St. Joe’s, it is a detriment to scientific innovation, Arango Pinedo said.

“Even if the SJU budget does not rely on federal grants to the extent that it does in other universities, our research programs will still suffer. Even if St. Joe’s contribution is tiny compared to large research universities, it is not negligible,” Arango Pinedo said. “We do research in a number of subjects that few other people study. The government has a duty to support universities that engage in research that will benefit the country.”

Moelter said it may be too soon to say how researchers and institutions are preparing for funding cuts in the long run, but “the hope is still that things will normalize again,” while still keeping open the conversation about changes to the federal funding system.

“A lot of people think that the federal research funding system isn’t perfect,” Moelter said. “But there could be a way to talk about its limitations and address them in a way that’s different than how it’s been done so far.”

Lee-Soety said she and some of her colleagues have begun looking into alternative funding sources in preparation for the possibility that funding is cut or withheld. But there are some faculty who are already uncertain of when, or if, they will receive funding, even for projects that have been positively peer reviewed, Lee-Soety said, and the damage has been done.

“It’s painful, it’s devastating,” Lee-Soety said. “It didn’t have to be like this.”