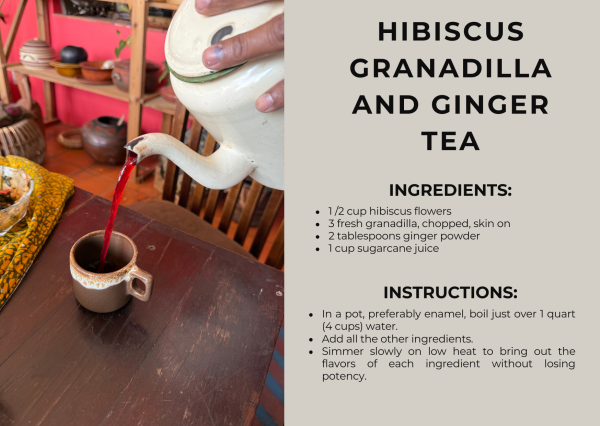

For Chef Noni Moroenyane, seated in the dining room of her home in Johannesburg, “food is medicine, and medicine is food.” PHOTO: MAXIMILIAN MURPHY/THE HAWK

JOHANNESBURG – When Nonhlanhla “Noni” Moroenyane first arrived in Johannesburg from the Eastern Cape in 1994 as a 9-year-old girl, her dreams were about survival, not about cooking. Certainly, she never dreamed of becoming a celebrated chef. The word “chef” didn’t even exist in her village. Young girls and women were just expected to cook for their families.

Moroenyane had been raised by her great-grandmother in Emjikelweni village, near the town of Sterkspruit in Eastern Cape province. Her home — a single-room mud house nestled between the Maluti and Drakensberg mountains and bordered by the Orange River — had no fridge or pantry. Meals came directly from the land and were prepared by her great-grandmother.

“We just went out and picked what we could, and we prepared a meal from foraging, from picking different herbs and greens — and boom, a meal is created with so much love,” Moroenyane said.

From an early age, Moroenyane learned how to create nourishing meals from what the land provided by listening to the plants and ancestors. This knowledge, instilled in her by her great-grandmother, now forms the heart of Moroenyane’s work.

Known today as Chef Noni, Moroenyane, 40, is a celebrated indigenous food revivalist in Johannesburg, herbal healer and founder of Noni’s Home Dish, a culinary business and teaching platform on Instagram and Facebook that blends ancestral wisdom with community healing and a deep respect for the land. She has also written an autobiography, “The Journey to the Beginning,” and a cookbook, “Noni’s Home Dish – The Great GrainMother’s Way,” both which she hopes will be released later this year.

Becoming Chef Noni

Moroenyane’s path from Eastern Cape girl to Johannesburg’s Chef Noni was anything but linear. After graduating from high school in 2003, Moroenyane couldn’t afford post-secondary education, so she took whatever jobs she could find. She worked as a waitress, a credit controller and eventually a pharmacist assistant after an employer paid for her to go to school. But the thread that carried her through these years was her connection to food.

“While I’m doing all of this, I’m a single mom,” Moroenyane said. “I’m studying, I’m working and I’m also doing the food thing on the side. So, when the children are sleeping, I’m taking orders, I’m preparing them and delivering them. I’m also putting together events around food, and then I decided, ‘I don’t like being here anymore. I really love this food thing.’”

Moroenyane quit her job as pharmacist assistant in 2019 without a plan or even the money to cover her rent. What she did have, however, was a love for cooking and an unshakeable conviction that she couldn’t keep doing something that didn’t fulfill her. Her landlord at the time offered Moroenyane a lifeline: 10,000 rand (about $558) to buy a stove and some pots to kick-start her cooking journey.

“He was like, ‘I see it in your eyes. It’s OK. You can quit your job, even if you owe me money. One day, you’ll pay me, but go follow the dream,’” Moroenyane said.

A home-grown philosophy

After graduating in 2020 from culinary school, where she cemented her title as “Chef Noni” and her devotion to indigenous foods, Moroenyane decided to start Noni’s Home Dish, named for herself and to honor the home-cooked spirit of her great-grandmother’s kitchen.

“The only thing I could think of when I ate food was home,” Moroenyane said. “I was raised by my great grandmother, and we had nothing … She would make bread, and if bread was all we’re eating the whole week, you could feel her spirit in there.”

That sense of love and nourishment became the foundation of her business. It draws on her upbringing, where survival meant knowing how to transform wild amaranth greens, pumpkin and ancient grains, like sorghum, into deeply nourishing meals.

“I’m wanting to really take the magic that [my great-grandmother] had with preparing food, the magic of love, of comfort when you have absolutely nothing, and that food just becomes everything,” Moroenyane said.

Every plate is a story, incorporating native grains like teff, sorghum, fonio and millet, which she calls her “living ancestors.” She forages greens and cultivates herbs, and many ingredients are grown right in her own garden.

Moroenyane’s cooking, which is now entirely vegan, is rooted in her belief that “food is medicine, and medicine is food.”

“There are whispers that show up,” Moroenyane said. “There are spirits that show up in my kitchen … a beautiful voice that says, ‘OK, I know you made that last week, but let’s do it like this this time. Add that. Stop. Now, add that.’”

Healing through food

Noni’s Home Dish has become a touchstone for a growing community of people hungry to reconnect with forgotten food traditions, and themselves. Alongside her business, Moroenyane teaches children in her community about ancient grains and plants and runs cooking classes for youth who are unable to access formal schooling.

“Coming from a community, collaboration is key,” Moroenyane said. “You cannot sit there by yourself and say, ‘This is my thing.’ No, it’s not yours.”

Moroenyane also participates in seed exchanges with other like-minded members of the community, seeing these exchanges as sacred acts of preservation and reciprocity. For Moroenyane, seeds carry indigenous knowledge, community history and ancestral power.

“There’s information and wisdom in there, indigenous knowledge that lies in every seed that has been here,” said Moroenyane, pointing to seeds in a glass jar on her dining room windowsill waiting to be planted in the ground.

Moroenyane’s three children are growing up with the same land-based wisdom that shaped their mother. She teaches them to cook with grains, forage for greens and understand the spiritual role of food in their heritage.

Indigenous plants and seeds “are very important to us,” said Moroenyane’s 9-year-old son, Selassi, whose favorite food is his mother’s falafels, made of pearl millet, mushrooms, mung bean, chickpea flour and a fresh herb mix. “Seeds give food.”

Cheri Lopez, founder of The Journey Home Project, a Johannesburg-based non-governmental organization working with unhoused and vulnerable youth, takes photos of Moroenyane’s food for Noni’s Home Dish. The two first met in 2019 when they began collaborating on community food security projects during covid-19, providing meals and nutrition education to at-risk youth.

“She taught me about indigenous foods, what grows here, what the value of what is meant to grow here, when we go back to our ancestors, what she teaches me about the land, about the soil, about the grains, about how they have a spiritual meaning,” Lopez said, “I didn’t understand that until I’ve been around her.”

Now working through her own community garden initiative, Lopez credits Moroenyane with helping her and many others understand that food is both fuel and a return.

“We’ve talked about this a lot lately, that we’re feeling an urgency,” Lopez said. “The time is now. We have to teach as much as we can to as many people as we can.”

For Moroenyane, that urgency carries a spiritual weight.

“My prayer is that the seeds I have given out somehow make it to the ground, to the soil, and that the rains fall and that the sun nourishes and the soul nourishes and protects the information and the wisdom in there, the indigenous knowledge that lies in every seed that has been here,” Moroenyane said.