Effects of the recruiting process on Division 1 athletes

For children who grow up playing sports, becoming a Division 1 college athlete is often the ultimate goal. As they grow and enter high school, the pressure to get the attention of college coaches skyrockets.

The recruiting process seems to be starting earlier and earlier with each year despite the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s (NCAA) extensive rules about contact with student athletes before their junior year of high school. There are ways to evade these rules though, including unofficial visits, phone calls and emails.

Head field hockey coach Lynn Farquhar has seen numerous student athletes come through her program and has been recruiting in her three years as head coach.

“We watch a ton of high school students, so a lot of times, we see players when they’re younger and before they hit high school, but for each program it’s a little different,” Farquhar said. “For us, we commit at the end of sophomore year at earliest.”

With the growing popularity of youth club field hockey programs in recent years, coaches have more opportunities to scope out national level players in tournaments that showcase students as young as middle school age.

The danger of having teenagers consider college athletics so early is the fact that they have so much time to change their mind, which is something that freshman field hockey player Quinn Maguire recognized in her own recruiting experience.

“A lot of kids pick [a college] when they’re young and then want something different,” she said.

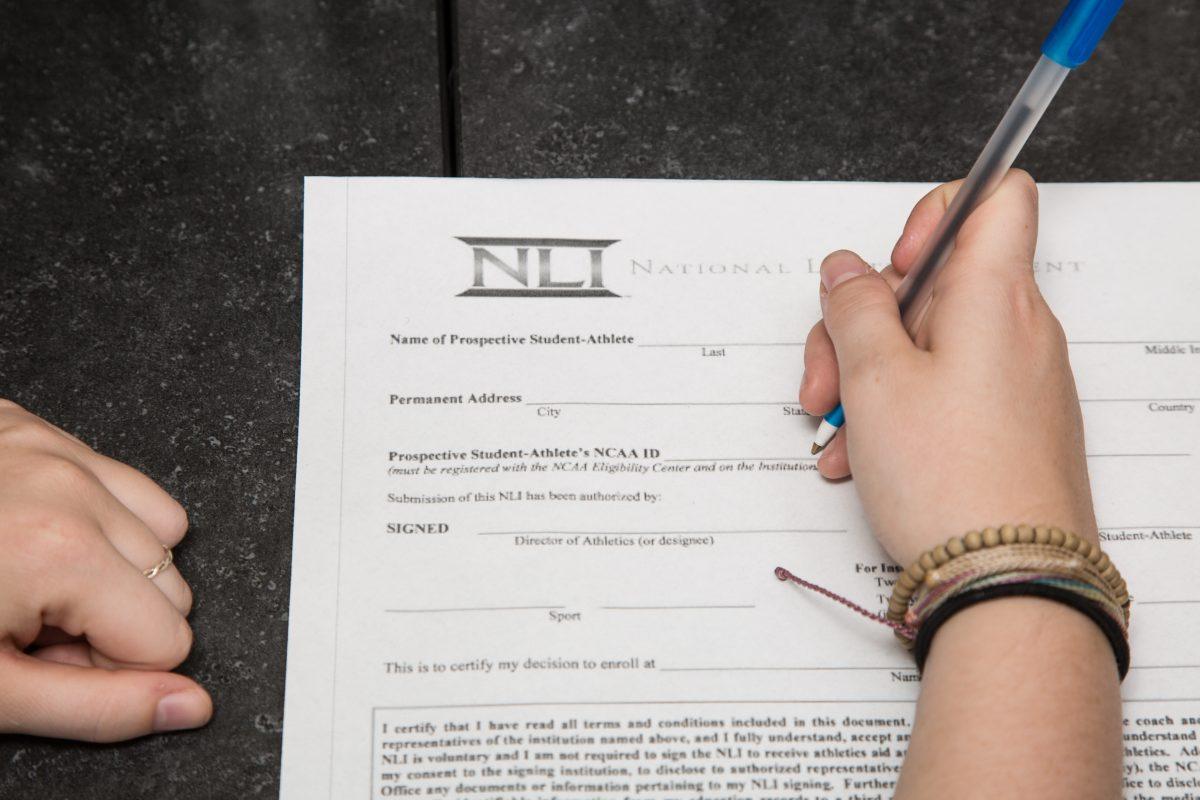

Luckily, students have the opportunity to change their mind with no problem until they sign their National Letter of Intent (NLI). If a student signs an NLI and wishes to transfer to a different school, they lose one year of eligibility, according to NCAA, but are still able to play for the rest of their college years.

The fact that recruiting is continuing to take place earlier in athletes’ careers is not only due to colleges chasing prospects. There are numerous factors that play into it.

“There’s a huge push from parents and club programs as they are more prevalent,” Farquhar said. “You see students committing to one sport earlier in their lives, investing their time in that sport. There are external pressures from high school students seeing their peers commit; parents have that as well.”

Essentially, athletes and their parents want to stay ahead of the game to ensure they have a chance of playing and earning scholarships.

Farquhar is careful in choosing new recruits and is very particular about who she wants representing her program.

“They have to fit with us at the university,” Farquhar said. “We’re Jesuit, so that is something every prospect enjoys and finds value in. There’s a fit in our program, so we lay out our mission statement and our plan that we challenge our student athlete to engage and contribute. Our prospects should enjoy the challenge of creating something new.”

For Maguire, the recruiting process was a success in the end.

“I handled it [the recruiting process] pretty well,” Maguire said. “It’s stressful trying to figure out what college you want to go to when you’re an underclassman in high school, like whether I wanted to stay close or go farther from home. I think I handled it well for how young I was.”

According to Farquhar, men’s and women’s lacrosse are two sports working on implementing rules to hold off recruiting until later in students’ high school careers. Whether or not the NCAA will follow suit is currently unknown.

Until then, athletes as young as junior high will have the question of where they will play in college in the back of their minds.