St. Joe’s professor reflects on the column he wrote 60 years ago

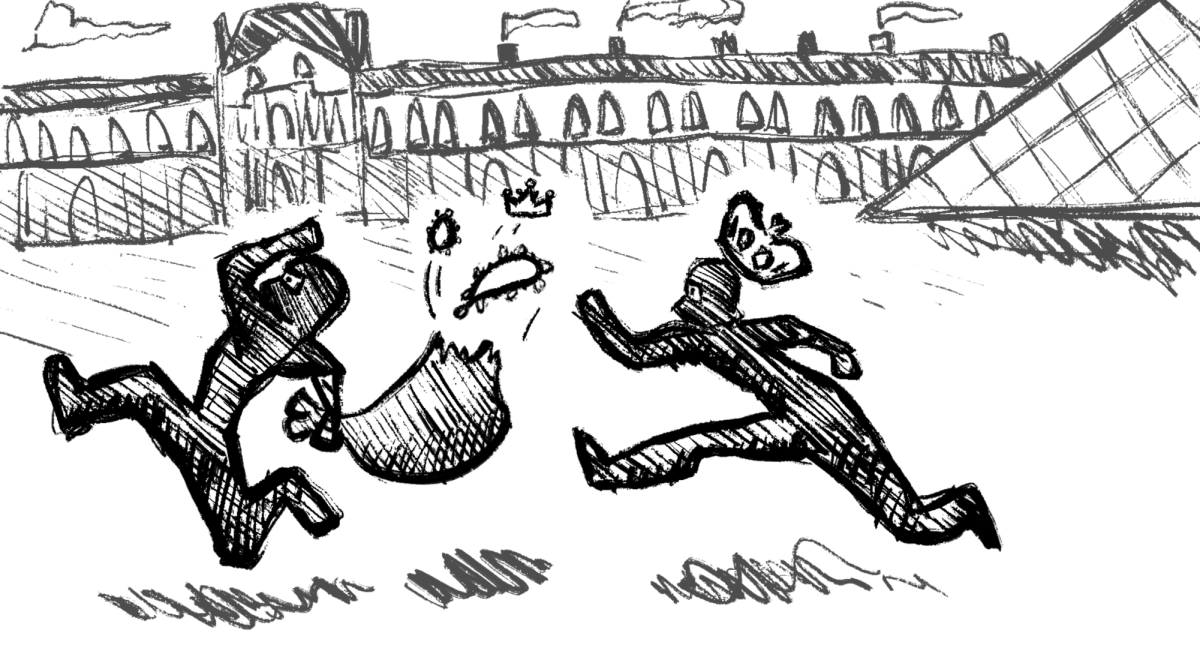

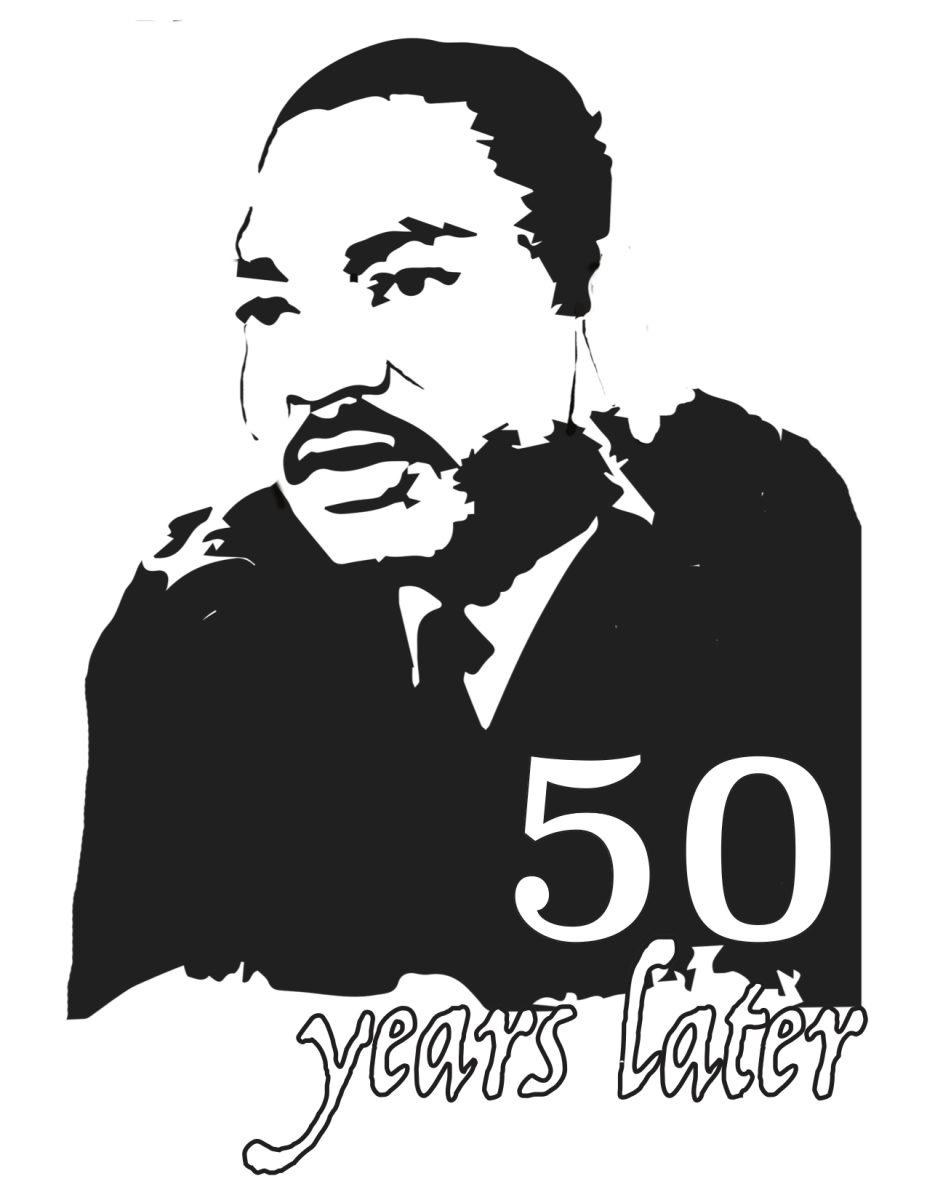

Sixty years ago, The Hawk staff writer Francis J. Morris ’58 wrote a column in response to racial unrest in Montgomery, Alabama, the city’s boycott, and retaliating violence against Martin Luther King Jr.

In his column, Morris, who went on to earn his Ph.D. and return to Saint Joseph’s University as an English professor, where he taught for over 50 years, called for an end to segregation through mutual understanding on all sides.

“The solution to the multi-sided segregation problems of Montgomery, and for that matter, of the entire South, undoubtedly requires the exercise of good will by both parties,” Morris wrote.

Morris said he now understands how naïve that sentiment was.

“I implied in the tone of that in the end of that last paragraph this was simply a matter of attitude adjustments,” Morris said. “I don’t think any serious, mature civil rights leaders ever thought that.”

In 1955, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) took action against the Jim Crow segregation laws by planning the bus boycott in Montgomery. Rosa Parks was chosen as a leader in this boycott because she had a clean record and was respected in the Montgomery community. Parks refused to give her seat up to a white woman on Dec. 1, 1955. The police arrested and jailed her, and by doing so, initiated the boycott that lasted a year.

“The purpose [of the Jim Crow laws] was racial segregation,” explained Randall Miller, Ph.D., professor of history. “The real purpose was racial humiliation and making sure that every black person understood that he or she was subservient to a white person.”

King joined the movement so that it could have a public face and a strong speaker at the forefront. Miller noted that, at first, King did not want to get involved with the boycott.

“He was a young minister, an intellectual,” Miller said. “He didn’t want to get involved with local things.”

The boycott gained momentum as white allies participated, as Montgomery businesses supported the movement and the bus company operating in Montgomery lobbied for the NAACP’s cause. In 1956, the Supreme Court found that the Montgomery bus law segregating white and black Americans was unconstitutional, making the bus boycott a success.

Many major organizations across the United States reacted to the Supreme Court’s decision in different ways. Tia Noelle Pratt, Ph.D., visiting instructor of sociology, researches identity formation among African American Catholics and systemic racism in the church. She found a statement from the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) released soon after the Supreme Court decision.

“Can enforced segregations be reconciled with the Christian view of our fellow man?” the statement asked. “In our judgment, they cannot.”

Pratt found that the USCCB argued compulsory segregation is oppressive and that it denies basic human rights for African Americans.

“I do think it’s really interesting, in putting out this official statement so soon after the bus boycott ended that it doesn’t mention the boycott,” Pratt said. “It talks about the harm that legal and compulsory segregation causes, but it doesn’t talk about this very specific form and that it had played such a major role in the country.”

The USCCB statement of the 1950s best describes the atmosphere in which Morris was writing. St. Joe’s, as a university located in a northern city, was geographically removed from the Jim Crow laws of the South.

Morris described the attitude of students on campus during his four years as being simplistic and passive. The national coverage brought by the bus boycott was some students’ first experience with outright segregation laws, which may explain why they would misunderstand the dark implications of such policies.

Today, Morris said he not only understands the errors in his way of thinking, but also sees hope in a new generation’s ability to recognize the need for direct action, such as the boycott, as well as the need for leaders to stand up against racial injustice.

He also said that because of the Jesuit education at St. Joe’s, students should be implored to learn both about the root of the cause of systemic racism.

“The original sin in American life was the institution of slavery,” Morris said.