Exploring art therapy and transformative prayer

I had my first taste of art meditation while attending 4:16, a Jesuit retreat for upperclassmen St. Joe’s Campus Ministry runs once a semester. While I was there, I was fascinated by clay meditation, an alternative form of prayer that works through the physical act of molding clay to focus thoughts and intentions.

When I learned Campus Minister Jackie Newns also offered a 30-minute guided meditation using watercolor painting, I signed up as soon as I returned to campus.

My first painting session with Newns fell right in middle of my final week of classes, when stress was high, and free time to devote to pleasures like creativity and meditation was at its lowest. All the more reason to give art therapy a try.

I met Newns in her office in Wolfington Hall on a Wednesday afternoon. She led me to a small room on the third floor, a surprisingly sunny space with windows overlooking the central part of campus and a few soft green couches arranged around a coffee table. Though a plaque on the door labeled this room the conference room, nothing about it felt like the right location for anything involving the word “therapy.” But then again, I was already aware the experience would be unlike traditional therapy in many ways.

Art therapy has long been used as a treatment method for reducing anxiety, fostering self-awareness and reconciling emotional troubles. Often used with patients working through emotional trauma, art therapy can serve as an outlet for those who struggle to verbalize their worries.

While I don’t know much about therapy, I have taken my fair share of art classes before. As fun and relaxing as they were, I tended to be consumed by the pressure to create something beautiful. I saw art as primarily a something to be looked at, and less so as an activity.

“If you take away what’s on the paper, what is art but movement, emotion, openness?” Newns said when I first inquired about her sessions. It has all the ingredients of traditional therapy without all the structure.

This aspect makes it especially appealing to some students.

“I found out about art meditation from some friends in campus ministry,” said Victoria DiNaro ’17, who has led retreats at St. Joe’s. “We did it once at a 4:16 meeting. I wanted to give it a try because I thought it would be an exciting new way to find yourself through prayer that I had never experienced before.”

Newns began using art as a meditative practice after being introduced to it during a class in college. She found it to be a good way of centering her thoughts and resetting her mind during times of stress.

Though her take on art therapy as a personalized practice isn’t exactly the same as what’s offered in hospitals and treatment centers, it draws on the same tenets of relaxation and fostering a personal connection with what you create.

After grabbing a glass vase of paints and a few cups of water, we sat cross legged on the carpet in front of large pads of white watercolor paper. Newns asked me about my art experience and how I felt using watercolors. She explained some artists hate the medium because it’s hard to control, but then so is the spirit, she said. The water goes where it goes, and sometimes it’s best to just let things drip.

Newns encouraged me to keep in mind that like any prayer or meditation, the valuable element is the process, not the product.

“Try not to focus on what you put down on the paper, but the action that creates it,” she explained, demonstrating by letting the brush in her hand make free, sweeping strokes through the air.

Newns said she likes to let her hands and the movement of her brush reflect how she’s feeling. Maybe that motion is slow and fluid, or maybe it zig-zags back and forth. It could be soft-handed or forceful. Either way, you don’t need to think too hard or even look at what you’re doing. You just do it.

We chose paints, and once again, I was encouraged not to overthink the process. I selected a few small tubes of teal, green and purple paint and squeezed them onto the pallet as Newns reached for our papers and traced around the base of a glass container with a light pencil.

“It can be hard for some people to look at a blank sheet and feel comfortable jumping right in with the paint,” Newns said. That’s why she likes to start off with circle in the center of each page as a little bit of structure or a starting point

After returning our papers, Newns flicked the music on, and we began. I reached for a small brush first and dipped it into the teal paint. I swirled the brush around in the water before bringing it in a first tentative stroke around the edge of the circle. From there, it all flowed together.

When DiNaro first tried art therapy, she described the feeling of creating something while meditating as both relaxing and invigorating.

“I wasn’t really sure what to expect at first because I hadn’t really tried to use art in a more spiritual way before,” she said. “But once you get started, I feel like you get in this zone of working and things just start coming together.”

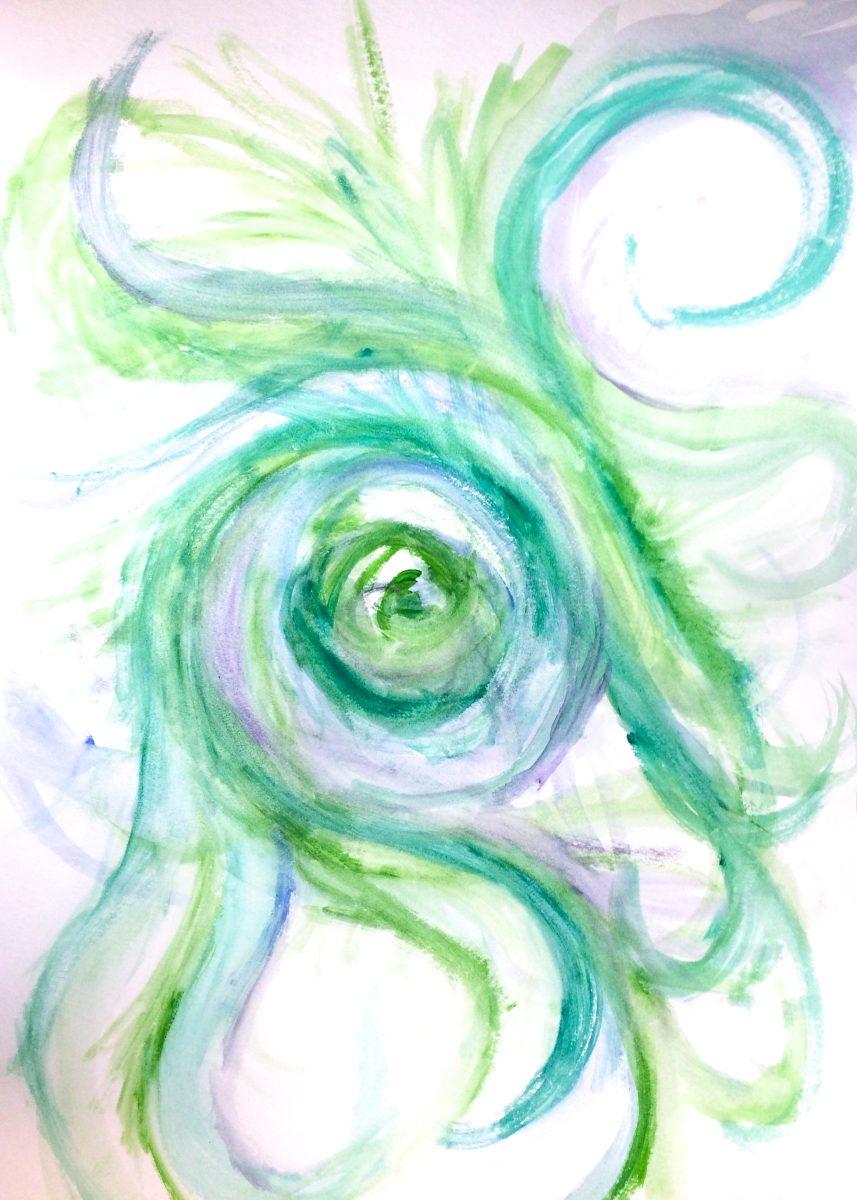

After a half hour, the soothing music from the speakers quieted and our paint brushes slowed to a stop. I looked at what I had made, something resembling an evil eye with tentacles, and wondered what the mass of green and blue swirls could possibly say about me.

Newns asked me to talk through my process, and nodded thoughtfully when I described sweeping the colors in different directions but returning back to the center for something bolder and less watered-down. She noted the amount of white space left on my paper, and said it was powerful to leave so much exposed, especially near the center of the circle. Maybe it isn’t necessary we always keep things so closed-up and covered, she mused.

I was shocked there could be so much to talk about in such a small painting. I found it easier than I expected to talk candidly about my emotions.

For people like me who tend to be hesitant about speaking candidly about feelings, it can be comforting to have art as separate element to focus on and direct my thoughts toward during this part of the session. This was also the case for DiNaro.

“You just kinda let the painting speak for itself,” DiNaro said. “Everything you feel is already expressed there on the page, so once it’s done you just have to look at the work and reflect. I always thought that was less scary than having to pull the thoughts from yourself.”

As for how well the sessions work, that seems to depend on how into the meditation one is willing to go, and how open one can be in the discussion afterwards. For some students, the effects are profound.

“It lets you see things within yourself that you might not have thought too much about before,” DiNaro said. “When I went, I was expecting to see a lot of my confusion expressed in the painting, but I ended up [looking at it and] thinking a lot more about growth.”

The same time the following week, we met in Newn’s office to discuss our paintings as well as our lives. Newns wanted to know if I had come to any more answers about some of the things I identified in my painting the week before. I surprised myself by finding so much to say. I talked about the shapes I initially interpreted as chaos possibly reflecting an action of reaching and of growth. Where I was looking to incorporate bolder colors might not be a search for certainty, just conviction.

Looking around Newns’ office, a sanctuary of pastel watercolors, trinkets, and pinned-up poetry, I asked her what she did with all of the paintings she completed. She said she keeps them all, as she believes it is an important part of honoring herself and the emotional process involved in the painting. But what about the ones she didn’t particularly like?

“This is one of the only things in my life I don’t feel I am critical about,” Newns said. “I think that it’s so important that everyone find something—whether it’s art or anything else—that they can do and believe that it is enough.”