Bessie Coleman: the first black woman to fly

When you think of Black History Month, what do you usually think of? For most it is Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Or is it Malcolm X’s stern expression beseeching black bodies to protect themselves “by any means necessary,” or even Huey P. Newton in full Black Panther Party regalia sitting in his chair with a spear in his left hand and a rifle in his right.

For me, Black History Month makes me think of one of the first black historical figures that I always wanted to emulate: Bessie Coleman, the first black woman to touch the skies.

A civilian aviator, born Jan. 26, 1892 in Atlanta, Texas, Coleman was the daughter of sharecroppers. Sharecroppers, like many other black people in the Deep South at the time, were still picking cotton, living a life of legal neo-slavery under stringent sharecropping laws. Coleman, with her family, sharecropped for years. Her circumstances as a poor black woman in the South nearly relegated her to a life most black people were forced into by a white-dominated American society, but Coleman never let circumstance define her path.

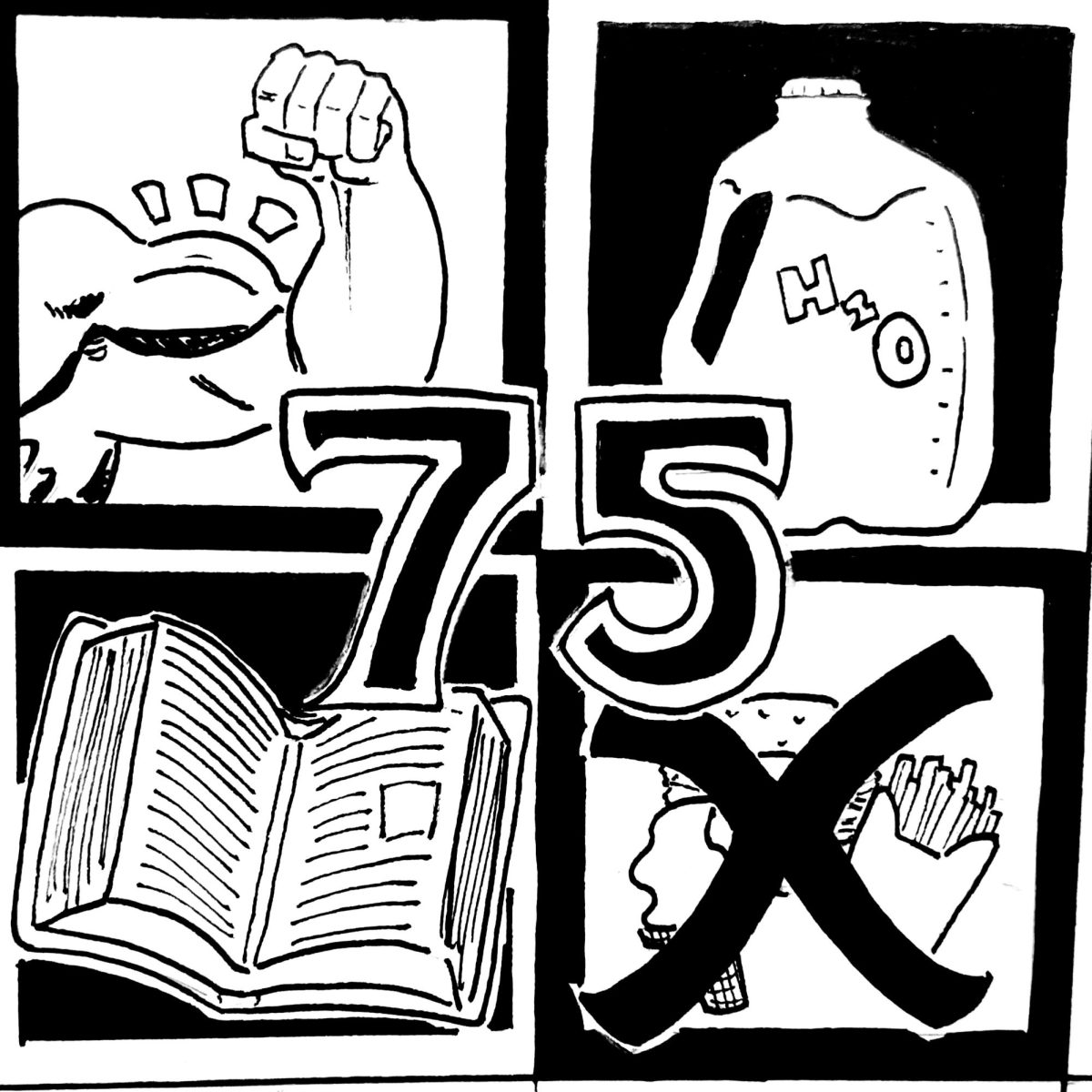

Coleman worked on her family’s farm until she was 23 years old before her moving to Chicago to live with her brother to find more opportunity in the North. It was in Chicago that her life’s calling and her historical significance came into play. While working as a manicurist in a barber shop, she overheard stories from pilots who’d returned home from World War I. Picking up a second job, Coleman began saving up money to pursue her piloting license. She soon found out that due to the blatantly systemic sexism and racism of the era, American flight schools would not admit women nor black people. So Coleman took the initiative to to travel abroad to get her piloting license.

It was in Paris on June 15, 1921, where Coleman became the first black woman (as well as first black civilian) to receive her piloting license. She would go on to have a career in stunt flying in front of desegregating crowds and develop plans for a flight school open to black people across the U.S. that would sadly not come to fruition. Coleman died at the age of 34 years old after being jettisoned from the cockpit of her recently purchased Curtiss JN-4 after it took an unexpected dive and spin.

While her life was short, her impact was large. Having been the first black civilian to procure their piloting license, she became an inspiration for those after her.

This legacy, hard earned and illustrious, sets Coleman among the vanguard of black historical figures, but she is usually pushed to the side as an obscure tidbit in history. Whether that is due to the prominent male-dominated, Civil Rights centric narratives of Black History or that of white-idealized revisionist history that hails Amelia Earhart as this pioneer in flight for women, I don’t know.

I truly appreciate Coleman because she was the master of her own life. She knew what she wanted to do and who she wanted to be, and her steadfastness in her agency and her choices makes her so important to me. At a time when black women were not allowed the mobility to really defy their societal circumstances, Coleman crashed through the glass ceiling and navigated the sky with ease.

My love for Coleman is as simple as acknowledging the fact that I didn’t have a poster of Rosa Parks on my wall, I had a poster of Bessie Coleman.

Coleman’s fight against adversity, for a little black girl from North Potomac, Maryland, meant that I could do anything, be anything.

Black History Month is all about remembering those that came before you, those who inspired you and still do. For some that is Malcolm X or MLK. For me, it is the first black woman to have the courage and the passion to touch the sky, regardless of the roadblocks in her way.