How race plays a role in the drug crisis

With any drug crisis in America, race has always been a contributing factor in the way Americans respond to the issue, and the opioid epidemic is no different. Americans are not only paying attention to the opioid crisis, but are trying to handle it with compassion. This is largely related to the fact that white people are most affected by the epidemic, according to Christopher Kelly, Ph.D., assistant professor of sociology.

“Unlike previous drug crises or scares, the response to this has not been calls for increased police activity, use of imprisonment for drug users and sellers, but instead overwhelming a call for a compassionate approach to people who have become addicted to opiates and opioids, an increased call for treatment options,” Kelly said. “That is perceived to be largely driven by who is associated with the drug addiction, which is white people.”

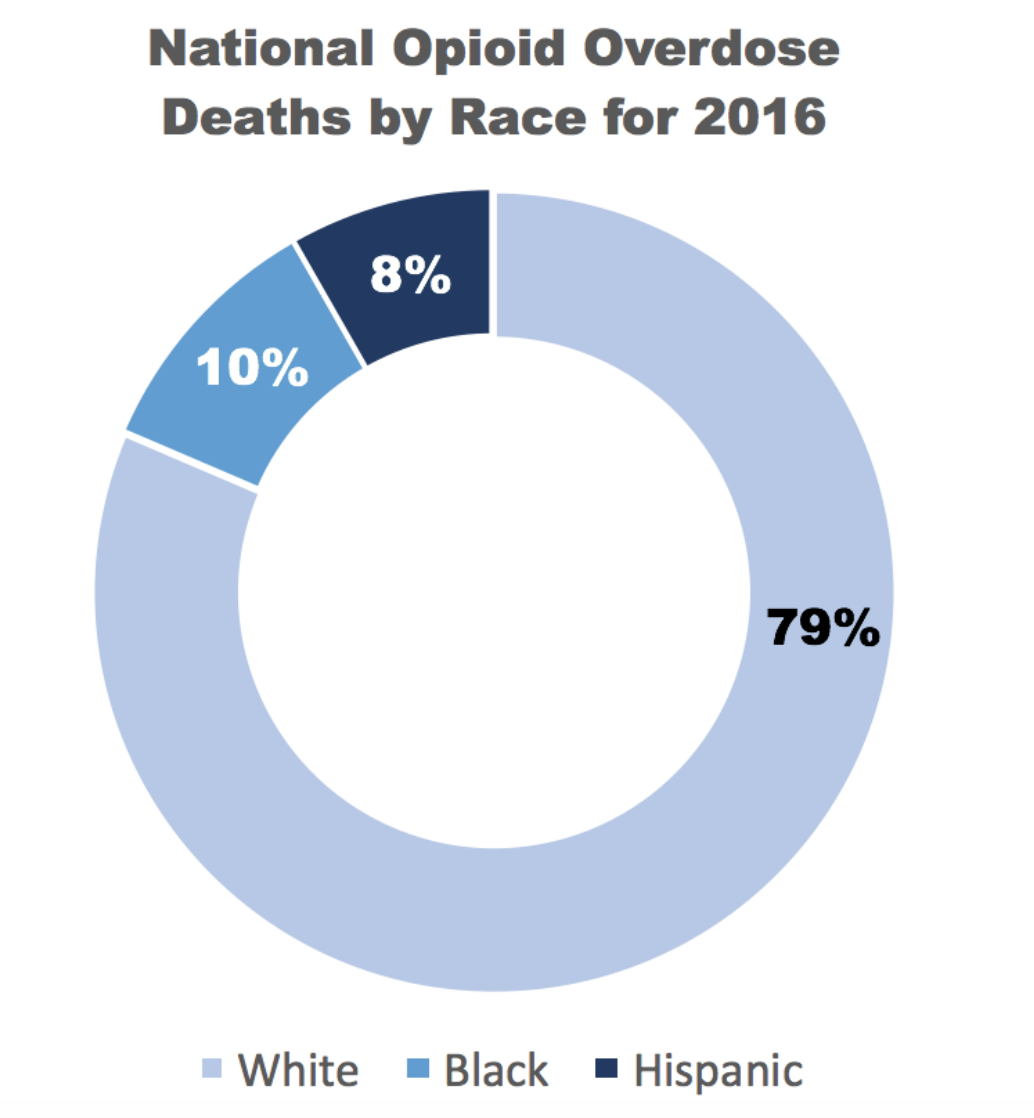

In 2016, an estimated 79 percent of deaths due to opioid overdose were white, with 10 percent black and 8 percent Hispanic, according to a study by the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

The large percent of whites affected is connected to the government’s decision to declare the opioid epidemic a public health emergency in 2017. This status opened up funds and resources for substance use treatment.

Katie Bean, assistant director of Student Outreach and Support and head of Wellness, Alcohol and Drug Education, said this is a positive response to the epidemic and a drastic move away from how drug crises were treated in the past.

“Now that the white people rates of overdose deaths from heroin or prescription pills, opioids and all that skyrocketed, it’s a different discussion,” Bean said. “It’s an epidemic. It’s a public health crisis. We need compassionate care to treat this disease, where that was never a conversation in the past.”

The racial conflict present in the opioid epidemic is not new, according to Kelly. It can be traced back to multiple points in America’s history, including the crack epidemic in the 1980s. The response to the emergence of crack cocaine was the War on Drugs, which called for increased police activity and incarceration.

“That drug war disproportionately affected African Americans,” Kelly said. “Even though crack cocaine was associated with African Americans, that was a misperception. White people used crack as well, but black Americans were overwhelmingly more likely to face punishment for it.”

Before the crack epidemic, there was another American drug war was in the 1930s, when Harry Anslinger, then-commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, called for a prohibition of marijuana, which Anslinger believed made African Americans and Mexicans aggressive and dangerous.

“The common thread between the marijuana prohibition and the emergence of crack and the enforcement against those drugs is that it’s not about those drugs,” Kelly said. “It’s about the people who are associated with using those drugs, and they are people of color, minorities, marginalized groups, where the powerful can enforce its majority against its powerless minority.”

Compared to past drug outbreaks, such as the crack epidemic, the language used to discuss the issue also has become more sympathetic, Bean said.

“The most obvious language to me is what the headline is now and what the headline was,” Bean said. “The war on drugs versus the opioid epidemic, a public health crisis. They’re very different when you talk about a health crisis and a war.”

Tia Pratt, Ph.D., visiting instructor of sociology, also said that race has influenced the attention the epidemic has received.

“The language used is that of a public health crisis, whereas the crack epidemic was the language of crime and criminality, especially since the public face of the crack epidemic was black and brown folks, but by no means were they the only people using crack,” Pratt said. “The public face of the opioid epidemic is white, and by no means are white folks the only ones in the opioid crisis.”

While race has always been an issue in drug outbreaks, Pratt said it has taken on a different tone now. However, it is important to acknowledge that white people are not the only ones suffering.

Bean said when discussing the opioid epidemic, we need to acknowledge that the response has changed, but it is still challenging for people of color to access the same treatment that whites have received.

“Go to different forums, talk to people in politics and say ‘what are you doing to help the epidemic?’ People of color are widely left out,” Bean said. “The communities we left out and criminalized, we’re leaving them out the solutions.”

Pratt said while the opioid epidemic has been rightfully treated as a public health issue rather than a criminal justice issue, there is still a need for conversation about the racial implications of the language used to discuss drug problems in America.

White people do make up the majority of those affected, but it is crucial to remember that people of color are a part of this crisis, as well.

“White folks aren’t the only ones that get addicted to opioids,” Pratt said. “It’s just that’s what we see, which we is why we have to be mindful of such things when we see media representations. Be mindful of what is an actual representation of what’s happening in our society, and that’s for all things, not just the opioid epidemic.”