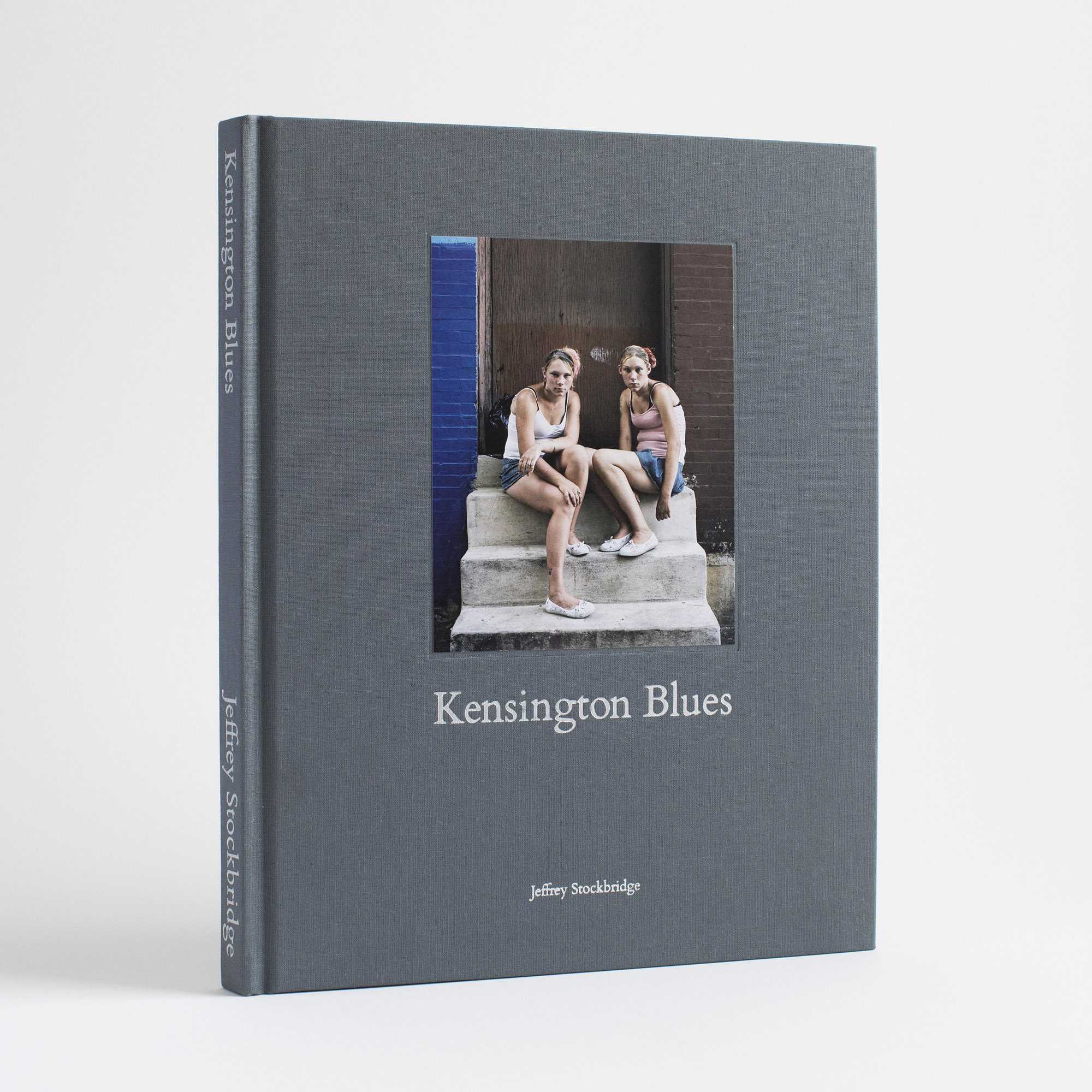

Photographer’s thoughtful portrayal of the opioid epidemic

Philadelphia-based photographer Jeffrey Stockbridge spoke about his decade-long project documenting the opioid crisis in Kensington, North Philadelphia, during a guest lecture in the Cardinal Foley Center on April 11.

Stockbridge was invited by Kelly O’Malley ’20, Julia Gray ’19, Cailyn Charlesworth ’19 and Eliza Rocco ’20 as part of a project for their Civic Media course. The course explores how people engage with social issues through media, and Stockbridge stood out to Charlesworth and her group members as someone who did this effectively in his project photographing people who with substance use disorder.

“Our professor talked about Jeffrey [Stockbridge] in class, and we thought the opioid crisis would be a good subject to focus on along with how people engage in that issue through different forms of media,” Charlesworth said. “He [Stockbridge] is a photographer, he does audio, he makes video, so we invited him.”

Rocco said they were also impressed by Stockbridge’s ability to tell people’s stories in a respectful manner.

“Jeffery’s work really respects and honors each individual’s life experience,” Rocco said. “He has been able to put [their life experiences] into a project that allows each individual to tell their own story through their portrait, written words and spoken words.”

Stockbridge said photos that accompany good writing in stories that report about the opioid epidemic are often problematic, and that media outlets that choose more striking photos of people using or overdosing limit non-user’s ability to relate to the users.

“My goal is to humanize people rather than dehumanize them,” Stockbridge said. “There are a number of elements in my work that involve a collaborative effort with subjects to tell a story.”

J. Michael Lyons, Ph.D., assistant professor of communication studies, teaches the Civic Media course and said he instills in students the idea that media-makers shape how people view social problems.

“I think the way we see these people is the way we treat them,” Lyons said. “Image begets policy to a certain extent. It’s important to understand who these people are and that they’re humans and deserving of some love and understanding as well as help.”

Stockbridge portrays the humanity behind drug use, according to O’Malley.

“He sheds light on the opioid epidemic that gives these people a story and identity,” O’Malley said. “There are a lot of people who photograph the opioid epidemic by showing actual heroin use, people shooting up, needles. Jeffrey Stockbridge gives more of an identity to it by showing the people who use rather than the actual using.”

Stockbridge works with a large format film camera to make his portraits, and he records audio and takes photos of written notes that people show him. His photography process often requires a time to set-up and get the camera ready for the portrait. According to Stockbridge, the time between deciding to photograph the subject and taking the photo is often when people relax and share their stories.

The time he spends with the people he photographs is what Gray finds so powerful about his work.

“In his photography, you can just tell the photos he takes are so personal,” Gray said. “He gives his subjects a chance to talk about themselves and get comfortable with him.”

Stockbridge said his appearance also plays a role in earning people’s trust.

“In Kensington, I don’t look that much different from some of the people I photograph,” Stockbridge said. “[And] I just like talking to strangers, I love getting to know people.”

Lyons considers work like Stockbridge’s to be a possible catalyst for policy change on societal issues like the opioid epidemic.

“Opioid addiction is this persistent social problem that we have not been able to figure out as a culture,” Lyons said. “The charge to the students is, how do people who make media provide a window into these social problems with the idea that we can then more easily solve them.”