The Philadelphia Flyers and the New York Yankees, two major American Sports teams, announced on April 22 that they will no longer play Kate Smith’s rendition of “God Bless America” during games.

This decision was made after the teams became aware of two of Smith’s racist songs recorded in the 1930s. The songs were entitled “That’s Why Darkies Were Born” and “Pickaninny Heaven.” Pickaninny is a demeaning term for a black child.

The Flyers proceeded to remove Smith’s statue, which has been outside the Wells Fargo Center since 1987. Flyers President Paul Holmgren released a statement on April 22 explaining the decision

“The NHL principle ‘Hockey is for Everyone’ is at the heart of everything the Flyers stand for,” Holmgren wrote in the statement. “As a result, we cannot stand idle while material from another era gets in the way of who we are today.”

The racism in Smith’s songs is also present in different forms of high school, college and professional sports teams across the U.S., according to Kalen Goodluck, a journalist and photographer who is part of the Diné (Navajo), Mandan, Hidatsa and Tsimshian tribes.

“[Mascots] are widely accepted across the United States and haven’t been totally viewed as something that’s inherently racist or offensive to Native Americans,” Goodluck said. “People don’t see or realize that natives are being bullied and harassed all across America.”

Goodluck said that while racism in sports is often directed toward the African American community, offensive and racist mascots are most prominent in the appropriation of Native American names, likenesses and imagery by sports team across the country.

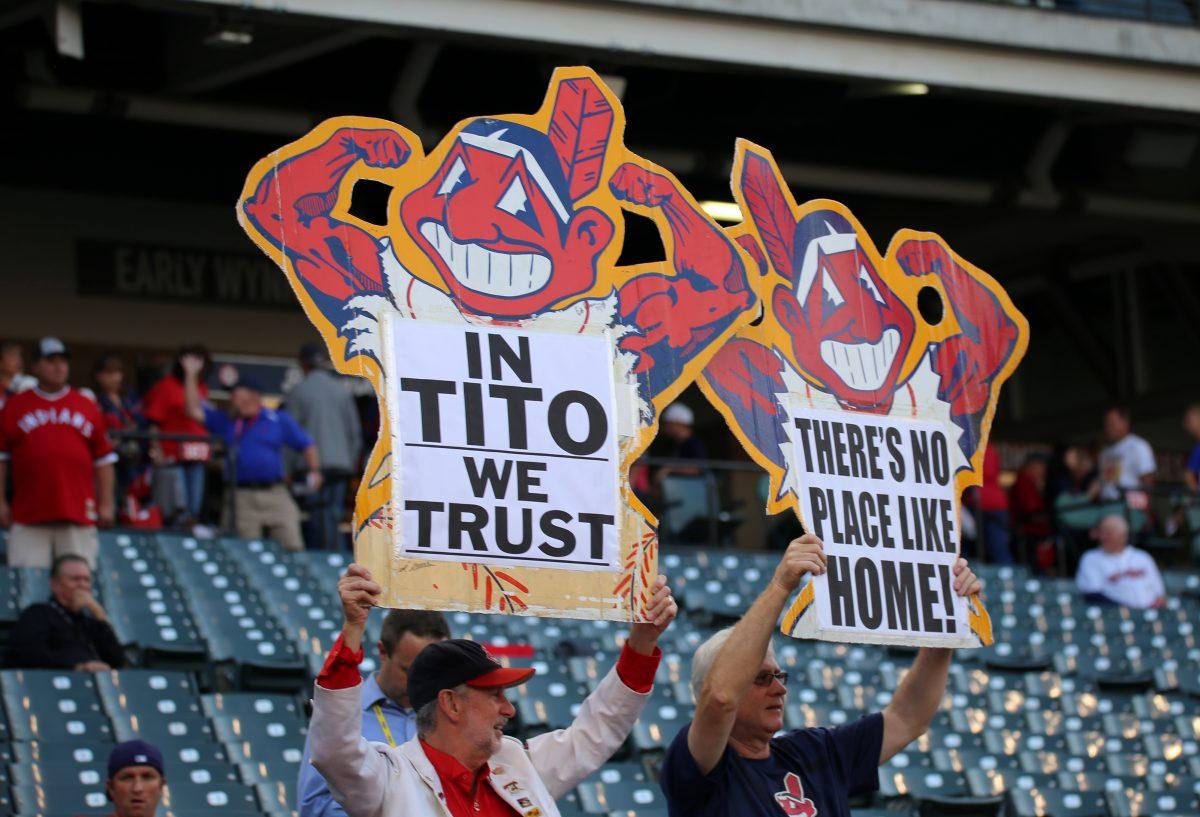

The NFL’s Washington Redskins and Kansas City Chiefs and the MLB’s Cleveland Indians and Atlanta Braves are major organizations who represent a form of bullying and harassment of Native Americans because of their team names, according to Goodluck.

“We’re seeing a slow change,” Goodluck said. “High schools are starting to make changes, professional teams are finally having to face those kind of demons.”

According to Stephanie Fryberg, Ph.D., associate professor of American Indian Studies and Psychology at the University of Washington, and a member of the Tulalip tribe, Native American people are rendered invisible by the racialized bullying of mascotry.

“The modern form of discrimination against native people is not recognizing Native contribution to the contemporary life,” Fryberg said. “The bullying, the psychological harm, is yet one more way of saying, ‘No you be quiet over there, we’ve allowed you to live, we’ve colonized you, and you’re here because we’ve allowed you to be here.’”

Jacqueline Keeler, the co-founder of Eradicating Offensive Native Mascotry and member of the Navajo/Yankton Dakota Sioux, said that sports organizations aren’t changing their racist team names because team owners think there will be pushback. Keeler said academic research from a 2013 Emory University study shows that teams, specifically in the MLB and NFL, have a lot to gain by changing their names from a profitability standpoint.

“Having a Native American mascot was actually off-putting to a lot of their fanbase,” Keeler said. “After they got rid of it, there was actually more participation. It makes you wonder, is there a silent majority that has other feelings but aren’t really able to articulate what those feelings are?”

Fryberg said people minimize the issues surrounding derogatory mascots.

“[People] say that natives have more important issues to deal with than Indian mascots,” Fryberg said. “In actuality, the Indian mascot is all about our identity. We’re undermining native people in a variety of ways and pretending like there are more important issues.”

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE WASHINGTON POST.

According to Goodluck, sports are framed by patriotism in American society, and that being in opposition toward Native Americans is deeply rooted in an “us versus them” American identity.

“By having these mascots, it becomes a war with no casualties,” Goodluck said. “Being able to say that you conquered a team like the Redskins perpetuates that idea of American identity.”

Keeler said Native Americans are heavily stereotyped, and people have to realize that it is unnatural that they are not depicted in the many ways that white people are depicted, especially in Hollywood movies.

“[White] People have always had their own stories,” Keeler said. “Native Americans are marginalized from those stories through the [dominant] experiences of white men and women.”

Fryberg said that there is a romanticized warrior image in these mascots, a “cowboys versus Indians” narrative.

“People don’t think about how when they put Native identity in this competitive platform, what it also means is that the other team is coming up with rhetoric to kill them, to scalp them,” Fryberg said. “At the heart of it, we’re talking about someone’s identity, in this case a group that has experienced oppression and discrimination in this country.”

According to Goodluck, names are historically important to Native Americans, and the military’s use of names such as “Tomahawk,” “Blackhawk” or “Operation Geronimo” tends to normalize racism.

“Valorizing how Native American land was taken away or competing against teams with Native American mascots is something that is extremely important to owners, athletes and fans,” Goodluck said. “It’s something that they don’t want changed.”

According to Fryberg, the fans and owners say they are honoring Native American communities through their mascots and coming from a place of respect.

“But the data of over 11,000 people shows that those are the same people who are not supporting measures that would increase the prosperity or material equity of native tribes,” Fryberg said. “The issues that really matter for tribal people, they don’t support.”

Goodluck said Native Americans are tired of the notion that teams are honoring Native American culture through mascotry and that changing Native-sounding team names would have a more meaningful impact.

“Native American activists have been fighting this for a very long time ever since the Civil Rights era,” Goodluck said. “[If team names changed], activist would see that as finally being heard.”