Every third Sunday of the month, African immigrants head to the church hall of Victory Harvest Fellowship in West Philadelphia for health screenings.

Members of the Hispanic immigrant community do the same on the fourth Sunday of every month at St. Francis De Sales Catholic Church in West Philadelphia.

The “Mercy Health Promoter Program” provides health screenings for Philadelphia’s immigrant communities. The screenings are part of a collaboration between St. Joe’s Institute of Clinical Bioethics (ICB), Mercy Catholic Medical Center (MCMC) and local church communities. Attendees of the promoter program are then encouraged to visit medical professionals at MCMC if their health screenings indicate they need proper medical attention.

Peter Clark, Ph.D., S.J., director of the ICB, said due to the generosity of Joseph DiAngelo ’70, Ed.D., dean of the Haub School of Business (HSB), the program now has an account at MCMC, which covers bloodwork, diabetes and hypertension medicine, and one X-ray for each immigrant who visits.

“We beg, borrow and steal to be quite honest with you,” Clark said. “We literally go out and seek donors. And the hospital provides all the free medical care if they are referred to the hospital.”

The promoter program is intended to be self-sustainable, Aloysius Ochasi, Ph.D., assistant director of academics and consultations of ICB, said. Members of Victory Harvest Fellowship apply and are trained to be community health promoters, so that around every two years the ICB can move on to implement the model at another church in the Philadelphia area.

“We pick members of the community, who [immigrants] are very comfortable with, to be part of the program,” Ochasi said.

Community health promoters are educated on the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), which protects health data integrity, confidentiality and availability.

“It gives [immigrants] a sense of assurance that whatever they tell [the community health promoters] doesn’t get out into the streets,” Ochasi said. “We want to make sure the community health promoters have some sense of dignity to respect them.”

Clark said it is necessary for this healthcare program to be based in a church setting because the majority of parishioners that they treat are undocumented, and they are worried that if they visit a hospital, they will be identified and ultimately deported.

“They feel more comfortable and safe in a church,” Clark said. “But also the problem is, who’s paying [for them to visit the hospitals]? They don’t have the money.”

MCMC found a need to kickstart this program with the ICB in 2010, when they saw that uninsured, undocumented African immigrants were frequently visiting their emergency rooms with end-stage renal diseases, more commonly known as chronic kidney failure.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, a non-profit organization that focuses on national health issues, in 2017 more than 45% of undocumented immigrants in the U.S. were uninsured.

The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA), a federal law that ensures public access to emergency services regardless of ability to pay, allowed the undocumented immigrants who visited the MCMC emergency room to be stabilized, with the federal government covering the fees. Clark said this process was not beneficial to those who came in with end-stage renal diseases, however.

“The problem is to stabilize end-stage renal disease, [you] have to dialyze, and once you start dialysis you can’t stop,” Clark said. “So who’s paying [for dialysis]? Obamacare will not cover the undocumented.”

According to Pew Research Center, Philadelphia has about 50,000 unauthorized immigrants, meaning approximately one in four foreign-born residents in the city is undocumented.

Clark said before the promoter program, the hospital was losing money when treating undocumented immigrants with end-stage renal disease.

“[At one point] they were paying for 10 undocumented African immigrants full freight for dialysis,” Clark said. “The question I posed to them was, ‘If you continue to do this and take in 15 more of these patients, will you put the hospital in financial jeopardy?’ And the answer was yes. We needed to do something. So proactively, we created this program.”

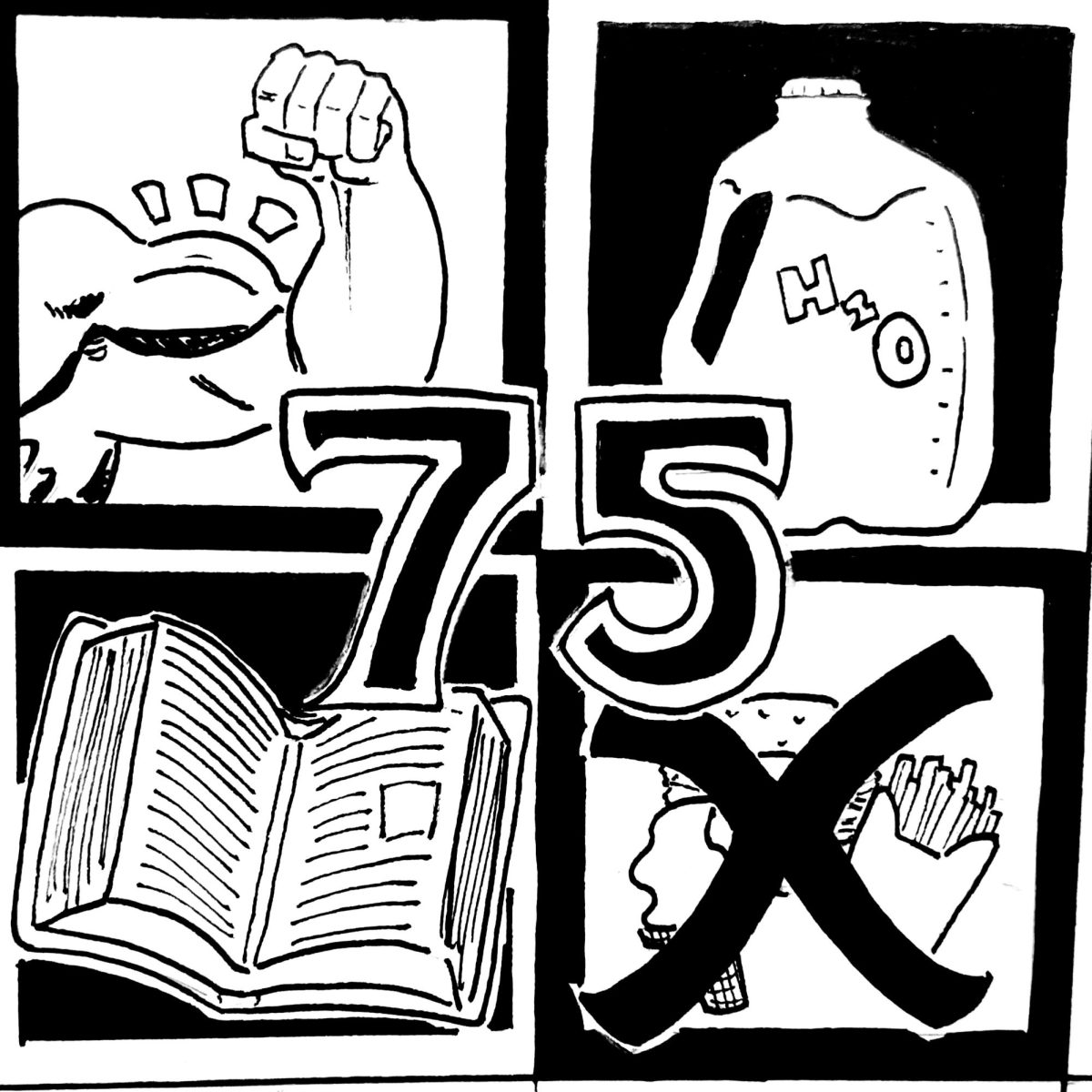

At the monthly screenings at local churches, tabling stations are set up for blood pressure, glucose and pulse oximetry testing, along with eye and dental clinics. Many people head to the screenings at the conclusion of church services.

St. Joe’s students, including biology majors, those from the Net Impact club and the pre-dental society Delta Delta Sigma, volunteer at the promoter program, along with students from the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine and some of Clark’s 150 medical residents at Mercy Health System of Southeastern Pennsylvania.

Clark said St. Joe’s volunteers are quite literally executing the Jesuit principles they are taught in the classroom.

“One of the great Jesuit ideals is taking care of the most vulnerable in society,” Clark said. “I can’t imagine anybody who is more vulnerable than the undocumented. Here [they] are treating those with dignity and respect.”

Letecia Zoeza, parishioner of Victory Harvest Fellowship and Liberia-native, frequents the blood pressure and glucose testing stations at the conclusion of Mass. She said she was especially happy with the free flu shots the promoter program was offering last month.

“Sometimes the jobs that I apply for, the first thing they ask is if I got the flu shot,” Zoeza said. “And we are supposed to pay for the flu shot. But this is free, so that [is] one of the good things I appreciate here because some [parishioners] don’t even have medical insurance.”

Zoe Hoag ’23, public health member for Net Impact, works at the babybox station at the promoter program, where she records how many prenatal vitamins and children’s vitamins she is distributing.

“If we see a pregnant woman or someone who just had a baby, we can give out a box that is basically a firm flat mattress, and that helps the baby from not having SIDS,” Hoag said. “Some of the bio kids are doing a study on that right now, so I’m helping them with data collection, and in general, Mercy wants to see, ‘Ok, is this working?’ We check in every couple of months.”

The ICB and MCMC have found that many undocumented African immigrants who attend the promoter program suffer from hypertension, while a majority of the undocumented Hispanic immigrants suffer from diabetes. But they weren’t able to solidify this observation because they were not properly storing the information, according to Justin Stout ’19, graduate assistant at the Pedro Arrupe, S.J. Center for Business Ethics.

“In the past, we did not have a proper identification system for our members,” Stout said. “Someone would come in, and we would give them a randomly generated identification

code. We were unable to do anything with that information so we weren’t able to actually track the care.”

Stout noticed when he volunteered at the promoter program as an undergraduate, the method of data collection was erroneous. They weren’t able to track patients in a longitudinal way and make conclusions over any trends of hypertension or diabetes that they were seeing.

Stout said the reason they collected data this way was because they didn’t want the undocumented immigrants to fear that this information was going to be used against them.

He decided to reach out to St. Joe’s student Net Impact club and see if they had any ideas on how to protect their identity while also collecting tangible data.

Taking on a lofty goal, Ryan Williamson ’21, data analysis project manager at the Arrupe Center and Net Impact member, created a data warehousing system to accurately collect and analyze the data. They now use Microsoft Access to log the “patient profiles.”

“The patient ID system is whether they are male or female and their birth date so that it’s anonymous,” Williamson said. “But the part that wasn’t here previously was that now it is holding previous data records. Now we are able to show them, ‘This was your blood pressure in January, and this was your blood pressure in February.’”

Clark said with the undocumented immigrants nervous with sharing any form of information, giving a detail as small as their birth date was a struggle.

“We had to really convince them,” Clark said. “I’m not sure how many gave their correct birthdays to be honest with you. They’re terrified of any identification.”

However, Stout said he has confidence that the undocumented immigrants won’t stop attending the promoter program now that they ask for this small piece of information because they have built relationships with these community members.

“We kind of built a reputation with these communities, and we are definitely here to help with these services we provide,” Stout said. “We have to trust our community members in the way they trust us.”