Environmental and social factors, which measure the societal impact of investing and corporate decision-making, are not a part of St. Joe’s finance department core curriculum, which troubles Carolin Schellhorn, Ph.D., assistant professor of finance at St. Joe’s.

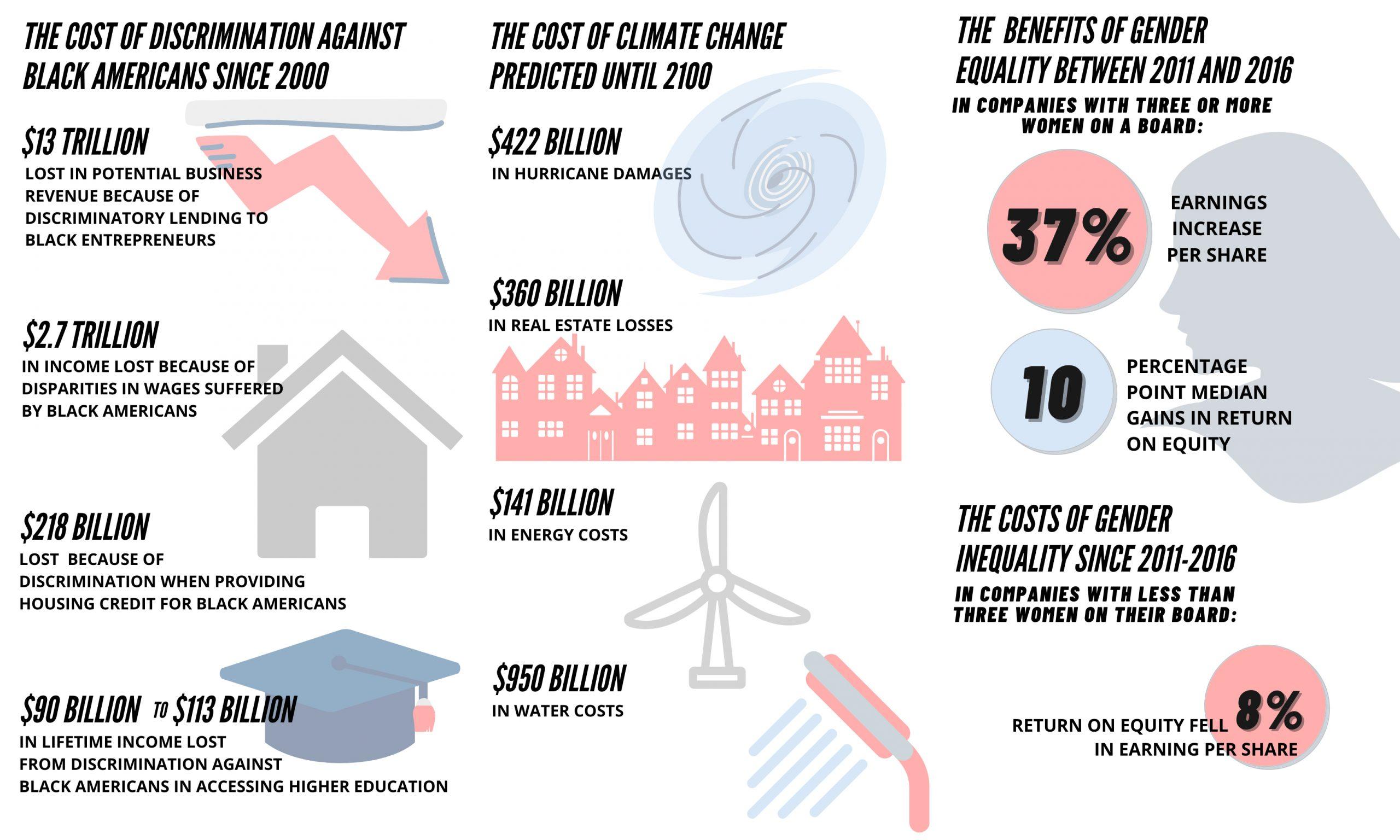

Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance (ESG) is an area of finance that helps companies understand the impact of their investments on the community at large in terms of environmental and social implications. Some systemic issues ESG focuses on include racial inequality and climate change. For example, a company that is guided by ESG principles might choose investments that do not negatively impact the environment.

Schellhorn teaches “Sustainable Finance” this semester, an elective that implements ESG into its course content. She said the current St. Joe’s finance curriculum, which does not substantially address ESG in its required courses, is part of a problem that finance departments in higher education, including St. Joe’s, need to address.

“[ESG] should be in every single mainstream textbook,” Schellhorn said. “It has to be attacked from all angles.”

Financial sustainability curriculum at St. Joe’s

One of Schellhorn’s students, Dominic Polidoro ’21, a finance major, is currently working with a classmate, Evan Campbell ’21, and an alumnus, Tim Ringelstein ’10, M.B.A. ’12, to research and present an action plan on how to address sustainability in the finance curriculum.

Polidoro said ignorance, as opposed to avoidance, has created a culture where ESG is not confronted in the Department of Finance.

“[Professors] weren’t taught it, so they don’t teach us that it’s important,” Polidoro said. “They frankly don’t teach it at all. We’re the next generation of professionals, and we’re just going to continue the problem. We have a lot of power in the future, a lot of economic power as well.”

Upon graduation, students in the Haub School of Business will be influencing substantial amounts of wealth invested both professionally and privately, according to Tim Swift, Ph.D., associate professor of management and interim director of the Pedro Arrupe Center for Business Ethics.

“Our students have become more conscientious consumers [with] a commitment to patronizing sustainable, ethical companies,” Swift said. “As students become more ethical consumers, it’s critical that they understand they can invest with impact.”

Joseph DiAngelo ’70, Ed.D., dean of the Haub School, said programs such as finance, accounting, management and leadership, ethics and organizational sustainability all substantially address ESG in their various curricula.

“That’s the whole premise of what we did in the center for business ethics,” DiAngelo said. “We wanted the topics to be infused throughout the curriculum so students could be exposed to them while also studying their disciplines.”

But applying ESG to investment decisions isn’t reflected in the finance curriculum or in the business school as a whole, according to both Schellhorn and Polidoro.

When asked how ESG is incorporated into courses in the finance department beyond Schellhorn’s Sustainable Finance course, Morris Danielson, Ph.D., professor of finance and department chair, declined to comment.

Swift said the Haub School relies heavily on GEP courses, including Moral Foundations, a course taught through the philosophy department, to help business students build a foundation in ethics. While all St. Joe’s students are also required to take an ethics-intensive overlay course, students do not have to fulfill that overlay with a business course.

In the fall 2020 semester, of the 37 sections of courses that qualify as ethics-intensive in the GEP overlay, seven of them were offered by the business school.

“I haven’t had a class that explicitly confronts those [sustainability] issues,” Polidoro said. “Sustainability when it comes to finance is something that is brushed under the rug and not enough people know about it. That’s the scary part for me. It’s our responsibility to just shed light on it because it impacts everyone.”

Neoliberal economics and ESG

ESG has been an area of interest among “investment activists” since the early 1970s, according to Steve Lydenberg, the founder of The Investment Integration Project, which helps investors to align their strategies with ESG.

“Corporate investing and social responsibility grew out of protest movements occuring in the 1960s,” Lydenberg said. “Concerns about peace, civil rights and the environment spilled over into the corporate world.”

Swift said the Haub School may not teach ESG extensively because the field is relatively new in the corporate landscape.

“It’s really developing and there really isn’t a standard way to incorporate it into our financial investment courses yet,” Swift said.

But Sandra Waddock, Ph.D., professor of management at Boston College, a Jesuit institution, has studied, researched and written about ESG since the 1990s. She said this isn’t a new topic and the research is widely available. Boston College also does not have required courses for finance students with a focus in ESG.

“It’s been studied to death,” Waddock said. “What you see with economists and finance people is a certain mindset. It’s a belief system, and they’ve totally bought into that belief system. There are many ways they’re indoctrinating their students with it.”

The mindset Waddock refers to is neoliberal economics, which focuses on maximizing shareholder wealth without taking into account all stakeholders and the societal impacts of business decision-making. Waddock wrote about neoliberal economic practices in a Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute article, “Reframing and Transforming Economics Around Life.”

“If you’re going to change the story, you’ve got to change the mindset so people can act differently and believe differently,” Waddock said. “You’re going to have to come up with a new paradigm.”

In the current paradigm, racism is not nearly addressed to the extent it should be in university finance curricula across the country, according to Rohan Williamson Ph.D., vice provost of education and professor of finance at Georgetown University.

“We need to look at parts of the economy from equity standpoints, focusing on areas where [Black people] are unable to invest, help the economy grow and help firms,” Williamson said. “This is something that has been part of the country for 400 years, and much longer globally. [Addressing racism] will require a push from universities to do more to bring these topics into our direct way of thinking.”

Williamson said Jesuit universities have a heightened responsibility to be leaders in addressing these issues due to the nature of the institutions’ social values.

“We have to live up to our ideals,” Williamson said. “It’s one thing to say something, talk is cheap. Now do something about it. It’s the responsibility of those who say the most to lead in these efforts.”

Shifting the business paradigm

Ringelstein works at Permit Capital Advisors, LLC and is collaborating with Polidoro and Campbell on their sustainability project. Ringlestein said companies have started to shift their investment practices to incorporate ESG, especially over the past five years.

“You have to be incorporating tenets for sustainability in business or else you’re not going to survive,” Ringelstein said.

Lydenberg has researched the social and environmental performance of corporations since 1975. He said while certain companies are starting to adjust their practices, there has not been a fundamental change, which contributes to how concepts are taught at the academic level.

“We’re at an inflection point,” Lydenberg said. “We’re going to feel the effects of climate change tomorrow, not just in the long-term future. If you let problems that are systemic in their nature sit, it’s very difficult to get them under control.”

Both Schellhorn and Waddock echoed Lydenberg’s point, citing how investors continue to finance fuel companies despite “the growing carbon bubble,” and how this mindset is reflected in academic pedagogy.

Waddock referenced Pope Francis’ 2015 encyclical, Laudato Si’, with respect to the correlation between Jesuit values and economics. The pope wrote, “maximization of profits, frequently isolated from other considerations, reflects a misunderstanding of the very concept of the economy.”

During faculty meetings, Schellhorn said she has brought up St. Joe’s finance department’s need to address and emphasize societal impact pedagogy, taking into account all stakeholders, like the pope references. She said she’s met with, “You’re so passionate about this.”

“I’m not passionate about it,” Schellhorn said. “I’m extremely worried about the current situation. This is very serious and very important for our continued survival. It doesn’t get more important than that.”