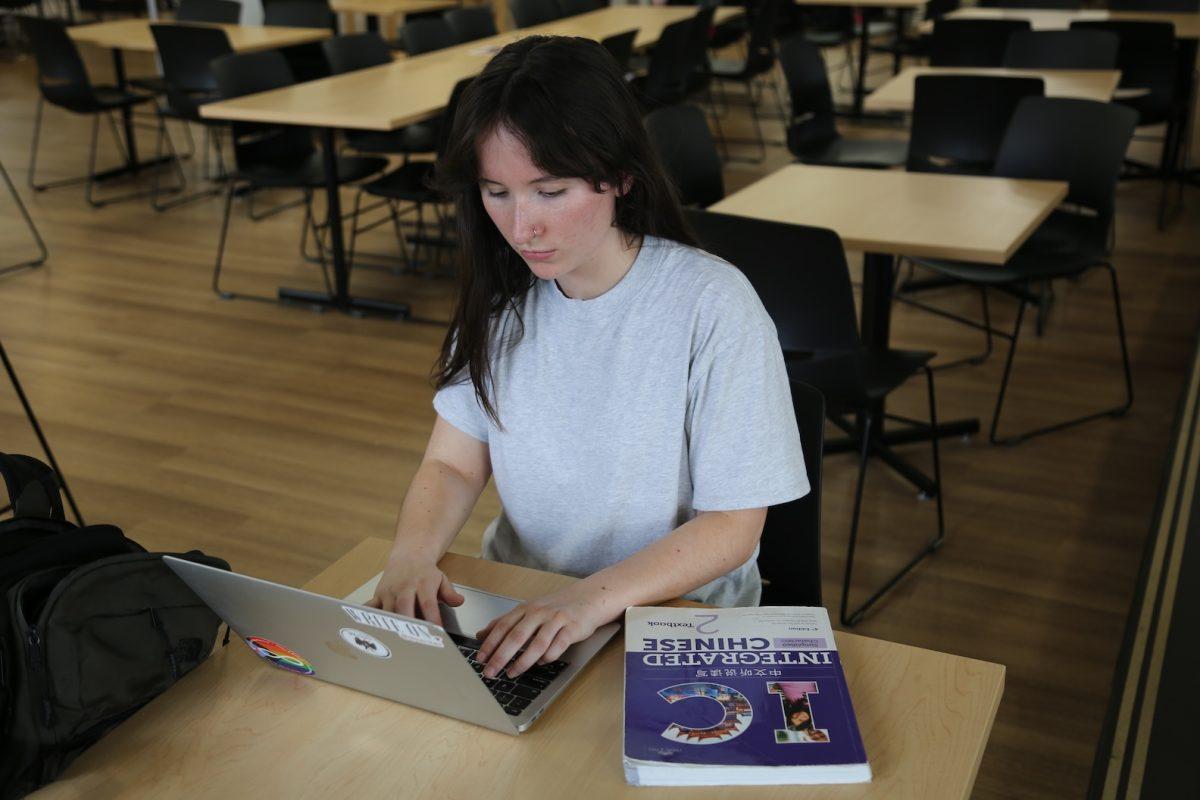

When Zoe Rhoads ’25 started taking Mandarin Chinese courses her first year at St. Joe’s, her classes averaged at around eight students. Now, her classes are about half that size, with her current section of Chinese Conversation and Composition II totaling four students.

While Rhoads, a Chinese language and culture minor, has ultimately had a positive experience with the program, she said the program’s small size has also presented challenges, such as the courses being taught by graduate students rather than a professor. Rhoads said because of these factors, “the responsibility to learn the language falls on the student.”

“It’s discouraging, because I feel like that external structure that you’re paying for isn’t there,” Rhoads said. “It’s very much what you put into it, you get out of it.”

Language programs dwindle

Thomas Buckley, Ph.D., chair of the modern and classical languages department and assistant professor of German, confirmed that St. Joe’s language department as a whole has been shrinking over the years.

For example, German has declined in popularity in recent years, with the major being discontinued in 2018 and the minor being discontinued in spring 2023, though some German language classes will still be offered in fall 2024. Buckley said three remaining German minors, two of whom graduate in May, are being taught out.

One reason for a declining interest in German, Buckley said, is the lack of German programs in high schools.

“In the case of German, there are fewer and fewer high schools that are offering it, and oftentimes, a teacher is retiring so they don’t look around for another teacher,” Buckley said.

Salar Alsardary, Ph.D., professor of mathematics, is fluent in Arabic and also teaches Arabic courses at St. Joe’s. The university began offering Arabic, taught by Alsardary, in spring 2023 following the June 2022 merger with the University of the Sciences. Alsardary said in his time teaching Arabic, he has seen declining numbers of students in his language classes.

Alsardary, who is also fluent in Kurdish and Turkish, volunteered to teach Arabic at the former USciences in 1996 after students requested courses in the language. Alsardary said he approached language faculty and created a sequence of two courses: Arabic I and Arabic II.

Alsardary said when he started teaching at USciences, without pay for a semester after being told the department didn’t have the funds for his courses, his sections averaged around 25 students, with an additional waitlist. Alsardary said he noticed a decline in numbers around 2017-18. His spring 2024 section of Arabic II at St. Joe’s consists of 10 students.

One school still offering both German and Chinese at the high school level is St. Joseph’s Preparatory School. Gina Gulli, chair of the modern language department at St. Joe’s Prep, said although the German and Chinese programs are smaller than more popular programs like Spanish, the school still encourages them.

“The biggest reason we still offer them is because the kids are still interested in taking them,” Gulli said. “They find value in the diversity of languages that are offered.”

Buckley said, at the university level, language majors have always faced difficulties with size. The current outliers at St. Joe’s are Spanish, French and Italian, with Spanish being the most popular major and minor of the three.

External forces present challenges

Another factor affecting the dwindling numbers in the modern and classical languages department — which currently has 13 faculty members — is the recent tenure buyout program, Buckley said. So far, he said four faculty members from the department are taking the buyout.

Buckley said St. Joe’s recently approved curriculum, the Cornerstone Core Curriculum (CCC), will also impact the language department. Proposed by the Core Curriculum Reform Task Force (CCRTF), the CCC changes the current non-native language requirement from two required courses for all majors to one.

Jim Boettcher, Ph.D., co-chair of the CCRTF and director of the General Education Program (GEP), said a factor influencing the CCRTF’s decision was feedback from a survey asking faculty which subject areas they viewed as essential for a core curriculum and which existing GEP requirements needed to be maintained. Boettcher said for both questions, less than 50% of responses deemed a two-course non-native language requirement crucial.

Buckley said the CCC’s proposed changes raise major concerns because the overwhelming majority of language students are recruited from within the university, specifically through beginner level language courses. Buckley said students may not gauge an interest in a language if only one course is required.

“When the new core curriculum goes into effect, it’s going to be more than just a struggle,” Buckley said. “It’s going to be a survival struggle.”

Boettcher said although a second non-native language course will no longer be required, students can take a second non-native language course as a way to satisfy a new mission overlay without having to take additional credits.

University follows national trends

The CCRTF’s decision to condense the non-native language requirement reflects broader national trends among universities, Boettcher said. Likewise, Buckley described the shrinkage of language programs as a “nationwide issue.”

“When you look at places like Boston College and the bigger schools, the more complex the school [is], the less likely it is that there’s a university-wide, non-native language requirement,” Boettcher said.

Data from a census published in 2023 by the Modern Language Association found enrollment in language courses apart from English dropped by 16.6% between fall 2016 and fall 2021, the largest decline in the census’ history. The two languages with the biggest decline were German (33.6%) and Arabic (27.4%).

Buckley, who said language majors are often labeled as impractical, added that the changed requirement has been not only a major concern to him, but also to his colleagues in the department.

“My colleagues are not just simply saying, ‘Oh, well,’” Buckley said. “They’re trying to think of ways [and] come up with something to attract students.”

Buckley said although students may not go into a career directly related to the language they studied, language courses are important because they teach critical thinking and analytical skills while helping students develop a broader cultural knowledge. He said these skills are especially important for those living in multicultural societies like the U.S.

“It opens up a brand new world that gives you more flexibility,” Buckley said.