Inequality in sports isn’t always reflected in something as large as pay disparity, a lack of media coverage or inadequate facilities and resources. Sometimes, it comes down to a single word: “women’s.”

In sports, as in life, language tells a story of bias. Women’s sports are often “marked,” framed as deviations.

“Marked’ means it’s out of the norm,” said Elaine Shenk, Ph.D., professor of Spanish and chair of the languages and linguistics department. “It’s not what you think of normally. So, if you take a noun like ‘basketball’ and you don’t add any adjective that modifies that, then that becomes the standard by which other things are judged.”

In other words, “basketball” means men’s basketball. “Women’s basketball” means women’s basketball.

“The person feels that they have to add ‘women’s’ basketball to mark that,” Shenk said. “It’s saying that that’s a different thing than the truth, than the noun itself. So, adding that adjective, or adding ‘women’s’ on there, means that the person is marking that as out of the norm.”

For women in sports, that adds up to a long history of linguistic othering.

Consider professional sports leagues. The National Basketball Association (NBA) is regarded as the norm, while the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) takes the marked term. In golf, there is the Professional Golfer’s Association (PGA) and the Ladies Professional Golfer’s Association (LPGA), or the U.S. Open Golf Championship and the U.S. Women’s Open Golf Championship.

“Everything goes back to how we have been socialized around sports, whether it’s watching sports or talking about sports,” said Stephanie Tryce, J.D., assistant professor of sports marketing. “Most of us still are socialized to watch men play sports, to encourage young boys to play sports, and aggressively. We have to ask ourselves, ‘How is the way we speak about women in sports shaped by how we’ve been socialized around sports from a young age?’”

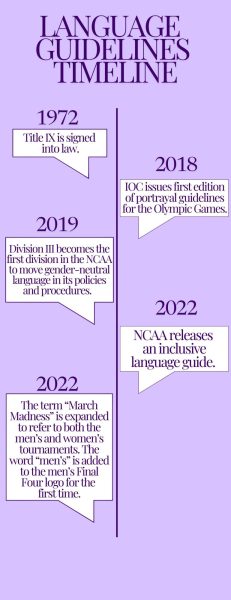

In 2019, Division III became the first division in the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) to move to gender-neutral language in their policies, procedures and formal correspondence on the recommendation of the DIII Student-Athletic Advisory Committee (SAAC).

The NCAA released an Inclusive Language Guide three years later, in 2022. That same year, the organization also expanded the term “March Madness” to refer to both the men’s and women’s NCAA Tournament. It also was the first time they introduced the word “men’s” into the men’s Final Four logo, giving both tournaments a marked term.

Shenk said to effectively combat gender discrepancies in language, this type of approach is necessary.

“If you’re going to mark it for one, you should mark it for both,” Shenk said. “If you’re not going to mark it for one, then you shouldn’t mark it for the other.”

Renie Shields ’82, senior associate athletic director for student experience and a former basketball player herself, has been a part of the St. Joe’s administration for over 30 years and serves on an advisory board that studies diversity, language use, signage and accessibility among students. During that time, Shields said she has dissected what it means to be inclusive within these guidelines.

“I think St. Joseph’s is ahead of the curve when it comes to that,” Shields said. “Our athletic director, [Jill Bodensteiner, J.D.], is always challenging us to do better in many areas, and one of them is to be open-minded and to really critically think. We’re not just going to think in terms of, ‘Oh, well, that’s a female, and that’s a male.’ It’s more of, ‘What’s the identification of that male, female, and how do we support them the best way we can?’”

The SJU Athletics website uses the marked term when talking about women’s or men’s teams for every sport in which both are offered. Women’s soccer. Men’s soccer. Women’s golf. Men’s golf.

Training and language guidelines, such as the ones released by the NCAA, are important in shifting the conversation. Tryce said these guidelines should be implemented with deliberate and conscious choices in mind so that women don’t continue to be minimized through these changes.

“We’re not going to talk about ‘the Hawks’ when we’re talking about the men’s team, and then talking about ‘Lady Hawks’ when we’re talking about the women’s team because it’s a way to reinforce the normalization of men in sport,” Tryce said.

Most universities have moved toward dropping the “lady” marking for their women’s team, but not all. At the University of Tennessee, all teams are the Volunteers after the “lady” differentiation was dropped in 2015. Only the women’s basketball team remained the Lady Volunteers as a nod to their storied tradition. At St. Joe’s, both men’s teams and women’s teams are referred to as Hawks.

“There was probably a second back in the day when they refer to the women’s team as ‘Lady Hawks.’ I don’t think that took at all,” Shields said. “We’re basketball players. That’s who we are.”

In the early 1970s, issues of The Hawk refer to the women’s basketball team as “Hawkettes.” Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the term “Lady Hawks” was used off and on in The Hawk’s coverage.

But issues with language surrounding gender in sports go deeper than marked terms. It’s also about the way athletes of different genders are described.

Hannah Prince, head coach of the St. Joe’s field hockey team, said she intentionally uses specific diction when speaking to and about the players on her team.

“I constantly try to use words like ‘strong, physical, feisty, gritty,’ as a way to, one, remind them that that’s what I see in them, and then two, describe them in that way to give them confidence,” Prince said. “Also, I think we’re at our best when we are playing with those characteristics, so I’d say that’s something that I try to define them as.”

Prior to the 2024 Paris Olympics, the Olympic International Committee (IOC) issued the third edition of their Portrayal Guidelines for Gender-equal, fair and inclusive representation in sport. First issued in 2018 and created at the recommendations of the IOC Gender Equality Review Project, the guidelines inform media covering the Olympic Games how to do so in a way that fosters inclusive language and reporting while dismantling stereotypes in reporting. These guidelines include a list of rules from avoiding defaulting to male pronouns to not focusing on the appearance of a woman athlete.

“When commentators speak of the name of the rugby player, [Ilona Maher], instead of saying ‘She looks masculine’ or ‘She looks like a man,’ how about ‘That’s one way an athletic body looks,’” Tryce said. “If we could disabuse ourselves of this notion that muscle means masculinity or something that’s manly only, we can get a little bit further in how we are speaking about women in sports.”

This conversation extends to how achievements are described as well. Oftentimes in women’s sports, a woman athlete’s achievement is met with language of shock and surprise rather than celebration.

“I just think to Caitlin Clark and how even with her becoming so popular, some of the hype was constantly still talking about the fact that she’s a female and it’s women’s basketball,” Prince said.

Still, “women in sports” is a broad term.

“I don’t want to forget about the intersections,” Tryce said. “How do we talk about lesbian women in sports, and are they ignored more? How do we talk about women of color in sports? There’s a difference, and it goes back to these entrenched stereotypes.”

While the language surrounding gender in sports has begun to evolve over the years, there is still progress to be made. Shenk noted that the conversation will continue to shift as societal norms change and women’s sports gain momentum, as they have in recent years. It will also require intentionality.

For Shields, it shouldn’t take much effort.

“As far as the sport, I don’t look at differentiation at all,” Shields said. “I think it’s the same game. We all have the same goals, and we all compete as hard as we can.”