Once considered the language of academia, Latin has diminished in higher education as more universities turn away from teaching the dead language.

“When we say dead language, it sounds so negative,” said Dominic Galante ’07. “But dead language really just means there’s no native speakers.”

In fact, scholars suspect the last native Latin speakers died around the seventh century .

Fourteen centuries later, Galante graduated from St. Joe’s with a degree in Latin. He now works at St. Joseph’s Preparatory School in Philadelphia, where he has taught Latin for the past four years. Students there are required to take at least two years of Latin.

But the university that helped launch Galante on his path is struggling to maintain enrollment in the Latin program. Prior to 2001, St. Joe’s offered a Latin minor, and the Latin major was created in 2001 by Maria Marsilio, Ph.D., professor emerita of classical studies, who also served as chair of the classical studies department.

In 2010, the Latin major was transformed into two different majors: a classical studies major and an ancient studies major. It was done to “prepare our students more thoroughly for graduate study in classics and for secondary teaching certification in Latin,” Marsilio said.

Both majors were discontinued as of 2022, and currently, two classic studies minors are offered: classical studies and ancient cultures. Official recruitment for the programs stopped after Marsilio’s retirement in May 2024. Only two remaining students are pursuing classic studies minors, and four are classical studies majors.

“SJU is experiencing precisely the same concerns about diminishing enrollments in Latin that many other colleges and universities are documenting at the national level,” Marsilio said.

Latin courses are still offered at St. Joe’s at the 101 and 102 levels through the department of language and linguistics for students looking to fulfill language requirements, but Marsilio said the implementation of a new core curriculum in fall 2025 that reduces the non-native language requirement from two courses to one makes Latin’s position even more tenuous.

“This will surely decrease all enrollments in the languages and will likely have the greatest negative impact on the smaller languages like Latin, German, Chinese,” Marsilio said.

Latin has been at the crossroads of changes in higher education for many decades now. The popularity of Latin in higher education started to fluctuate in the 1960s, when schools began removing the language as a requirement and the Catholic Church attempted to broaden its following by turning away from the traditional Latin mass.

In the 1970s, the back-to-basics movement brought about a revival of the language in the classroom. But, in recent decades, many colleges and universities have chosen to eliminate dead languages in favor of offering modern languages with a clear communication element.

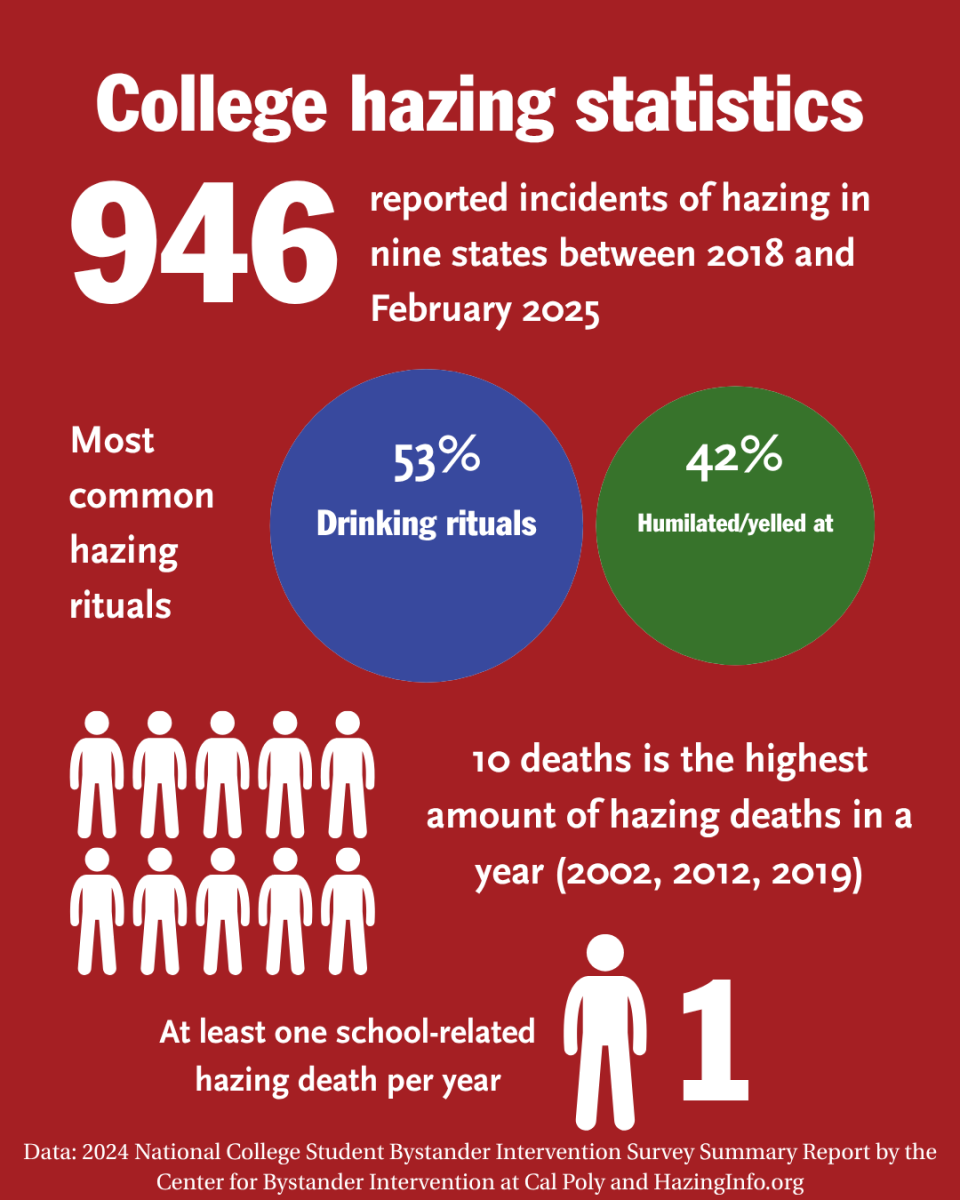

Recent data from the Modern Language Association indicates that there has been a gradual decline in Latin enrollment at the higher education level since the early 2000s. The most significant change occurred between 2016 and 2021, when Latin enrollment dropped 21.5% in the United States.

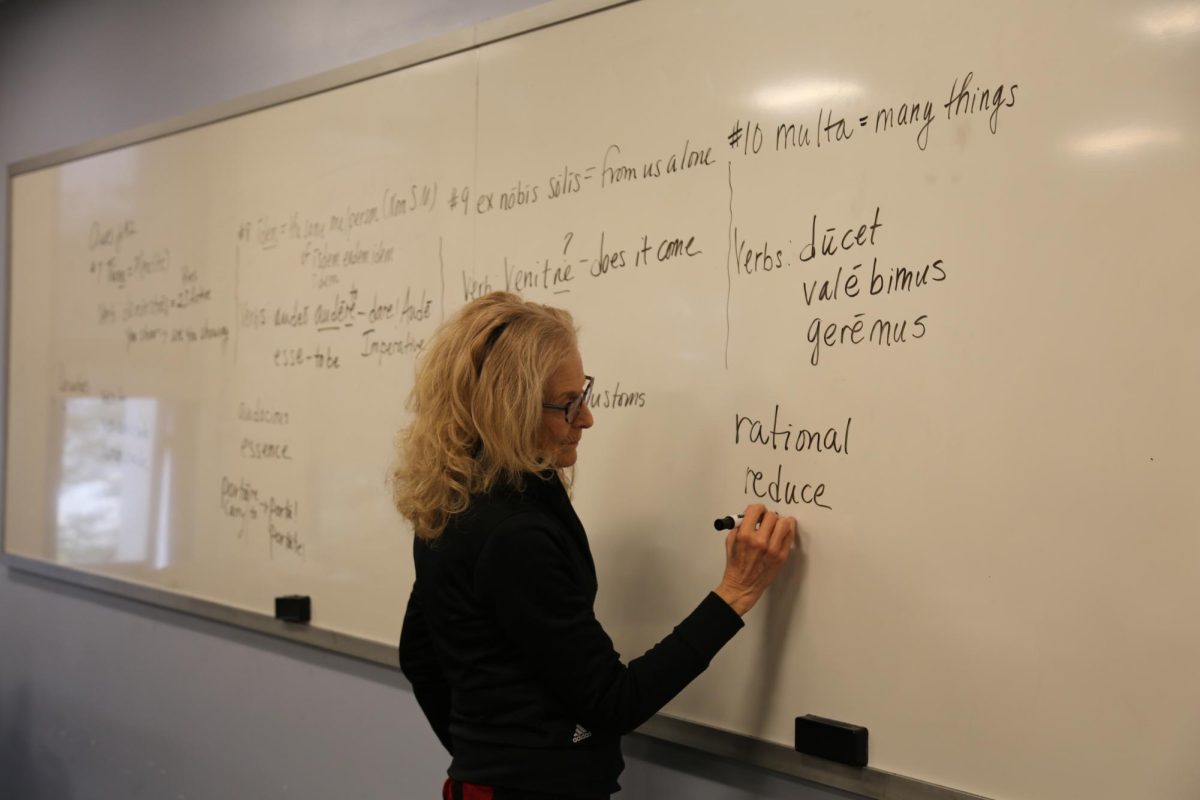

Mary Brown, adjunct professor of Latin, has taught Latin at St. Joe’s since 2017 and remains passionate about what Latin offers students, especially at a Jesuit university like St. Joe’s.

PHOTO: MADELINE WILLIAMS ’26/THE HAWK

“Latin and Greek might not sit in the administrative mission, but the Jesuit schools tend to be strong in maintaining Latin, and possibly Greek, because St. Ignatius used New Latin, and a lot of the typical Ignatian spirituality phrases are Latin phrases, like cura personalis and the magis,” Brown said.

But Brown, who has taught Latin in high schools and colleges for over 50 years, is working against a tidal wave.

Since 1995, the university has not offered more than two sections of Latin 101 and Latin 102 in any given semester, Marsilio said. That has been the case for 200-level Latin courses as well.

“In short, the Latin enrollments are not growing,” Marsilio said. “To the contrary, they leveled off many years ago, then began to diminish as more and more students selected other languages.”

In many cases, arguments against taking Latin stem from larger trends in higher education in which an emphasis is placed on prioritizing skills that will lead to a career after graduation.

“Latin is in this category of ‘not useful things,’ and so, therefore, it must justify its existence in our curriculum, which is a hard place to be in,” Galante said.

Chase Davis ’24, a classical studies major who studied Latin at St. Joe’s and is now a Latin teacher at Cristo Rey High School in Philadelphia, said he is disappointed that people dismiss the wide range of benefits from learning Latin.

“It not only enhances English speakers’ aptitude for grammar and understanding, but also provides that necessary introduction to linguistics,” Davis said.

Felipe Utreras-Castro ’25, one of the last four students who will graduate with a classical studies major from St. Joe’s following the university’s termination of the major, began studying Latin as a student at St. Joe’s Prep. To Utreras-Castro, studying Latin also brings about a connection to a larger culture.

“The desire when you read Latin is not just to learn a language. It’s to learn a culture, to learn a people,” Utreras-Castro said. “It’s like any language. You want to understand what those people thought, what those people felt, and how that still affects you in the real world.”

Davis noted that while Latin as a language may be “dead,” the world of academia has a larger role in its preservation.

“While it technically is already dead, you want to keep it alive,” Davis said. “If you were to 100% let it die, let it utterly fade away, you would be all the lesser for it.”