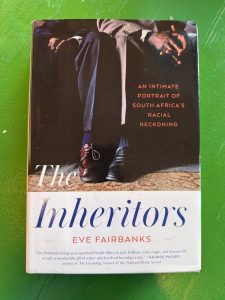

Eve Fairbanks, 42, is an American journalist and author based in Johannesburg, South Africa. Originally from Virginia, Fairbanks moved to South Africa in 2009 after working as a political writer for The New Republic in Washington, D.C. Her first book, “The Inheritors: An Intimate Portrait of South Africa’s Racial Reckoning,” published in 2022, draws from years of interviews and on-the-ground reporting to explore how ordinary South Africans live with the legacies of apartheid.

The Hawk sat down with Fairbanks in Johannesburg to learn more about her life abroad and the stories behind “The Inheritors,” which traces the lives of three South Africans over five decades: Malaika, a Black university student; Dipuo, Malaika’s mother, a Black former activist; and Christo, a white Afrikaner lawyer.

What drew you to move to South Africa? I just felt like I needed to get out of Washington and that there were too many reporters there, too much of a race for access, which compromised us. You had to not publish stories that were important in order to maintain your relationships with sources, to try to beat people for tiny scoops. So, I made up my mind to leave, and then I found an international journalism grant. I had to propose where I would go, and to be honest, it was going to be the World Cup in South Africa.

The introduction to the “The Inheritors” mentions your being surrounded by Civil War battlefields as you were growing up. Did that background also influence your decision to relocate to South Africa? My father’s from the South, the deep South, grew up in Northern Virginia, but it had a more Southern character, surrounded by those battlefields. To look at how another country navigated segregation, desegregation, radical changes in who held power in society, I came here and was like, ‘Oh, there was a deeper reason I was drawn.’ That’s probably why I stayed, which was not that it’s a mirror on my own upbringing or on the United States, but it has a lot of lessons.

Your work draws parallels between South Africa’s post-apartheid transition and America’s racial history. What parallels do you see between post-apartheid South Africa and current racial reckonings in the U.S.? I find in the narrative right now of South Africa in the U.S. that maybe apartheid was immoral, but white people were safe and secure, and now they’re unsafe. They were not safe. They were drafted into this horrific army. They lived in terror of it. Every white person interacted with Black people, as kitchen staff or gas pump operators or maids, and relationships were so policed and constrained. It was very painful for a lot of people. There’s this hesitance to talk about that because it’s not like [white people] suffered that badly comparatively, but it wasn’t good for these communities …

There’s a way in which the kind of country that some Americans believe they want on racial lines, but even in terms of the way history is talked about, the types of speech that are OK, the way history is taught in schools, the masculinity, the Christian values, really resembles the apartheid state … A component of people [in the U.S.] want to go back into something that I think the vast majority of South Africans, including white South Africans, will say, ‘Zero out of 10, wouldn’t do it again.’

What do you do in South Africa now? I do two things. I write, still. I’m working on a book that is not set here. I travel a lot. I do pieces set in the United States now. And then I edit a magazine called Foreign Affairs, which is based out of New York. But I’m still doing work here. I’m contributing to a chapter of a book called “The White South African Experience of Apartheid” and the negative components of that.

How does your background as an American writing about a post-apartheid society influence your perspective? I think it was very important that I was not here in the ’90s because there was a particular vision of the country that was never going to be possible — this is what I write a lot about — but that people were very invested in, and so much so that they feel a great sense of loss and a sense that somehow the country didn’t live up to expectations. I find [if] writers and reporters, either South Africans or foreign correspondents, were here in ’94, they will come back after 30 years, and there’s a pervasive sense of letdown, like [the vision] didn’t turn out. I would’ve been 10 in April ’94, and [apartheid falling] wasn’t on my parents’ radar … So I think that let me come in with a blank slate of like, ‘Actually, it’s quite incredible what people have managed to do with the history they inherited.’

As a white woman who moved to South Africa after apartheid ended, what was it like to tell a story you didn’t experience? The amount of privilege that white people have here is unbelievable, and it’s very pervasive. I would experience a level of respect and a belief in my good intentions that I think a Black journalist, and a Black South African journalist, would struggle [to], including within Black communities, because of this very, very deep and historical political degradation of the sense of the capacity of that community. I think that there were a lot of people who spoke to me who might not have spoken to a non-white journalist … I tried to encourage the Black people I was speaking with to be frank with me if they thought that my question was misinformed or hurtful or just dumb.

What did you hope the stories of Malaika, Dipuo and Christo would illuminate about post-apartheid South Africa? I have trouble thinking about how much I wanted to pitch this book to Americans, but in a way, I felt when I was writing it, maybe part of the sense of urgency came from like, ‘We have to learn lessons from this.’ Which, if I had to summarize them, was that these figures in the book were engaged in a deeply human project in their adulthood of trying to edit history, either of their own teenagerdom or even their communities deep past … These particular people ended up feeling, at times, like they had spent too much of their real, present lives struggling to edit and curate a version of their past. That, to me, felt like a lesson for countries and societies, as well as individual human beings — that this is a real risk, and you can fail to see the actual country that you’re living in. Also a thing that a lot of these people experienced was almost an inability to dwell in the real world that had emerged around them and that was still emerging.

What do you hope readers — especially those unfamiliar with South Africa — take away from “The Inheritors?” I ultimately wanted people to have an almost novelistic experience of some of these figures and see themselves in them and ask themselves whether they would have done the same thing, and if they wouldn’t have wanted to, what might have allowed them not to.

A big story in the U.S. right now is about so-called white genocide in South Africa. Why do you think certain politicians in the U.S. push this narrative? I think there’s a range of motives, but I think a really big one is there are people whose components of their politics are built on the premise that if they seed any power to people they know very well they have not treated as they ought to have … revenge will be sought on you, and it’ll be double. To the very fact that that did not happen in South Africa, and the fact that it isn’t happening, they’re not angry about the white genocide, they’re angry about the lack of it.

What do you wish Americans understood about this false narrative? I wish they would understand how much contempt the majority of white South Africans feel for the spokespeople that are making themselves omnipresent on American TV — that they’re actually very marginal figures here … [South Africa’s] got a very rich political life, very vibrant, very contested, very, very dedicated to democracy.