Taking a critical look at marginalization in the Church

When I graduate in May, I hope to move on to a career marked by public service and advocacy, to a life dedicated to finding just solutions to our country’s most intimidating problems, with economic and social inequality chief among those problems. One of the most important lessons I will take with me into my career is the role that my faith can play in my work within the public sphere.

Our Jesuit theology at Saint Joseph’s University teaches us that our faith compels us to be active citizens, seeking justice in all venues of life, especially government and public affairs. Understanding this obligation, I have learned to let my resolve in my faith drive my efforts, letting my faith act as my motivation in achieving justice for even the most marginalized.

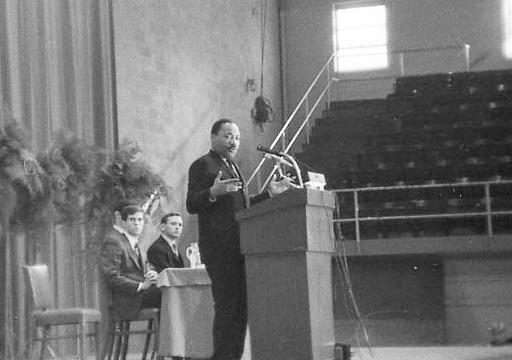

As our school celebrates the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr. visiting our campus, I was reminded of King’s words in “Strength to Love,” a 1963 collection of his sermons:

“The church must be reminded that it is not the master or the servant of the state, but rather the conscience of the state…It must be the guide and the critic of the state, and never its tool.” Here, King expresses the same obligation of the Church to work in perfecting the state that Jesuit theology teaches.

However, King’s quote has left me wondering: what sort of guide, what sort of conscience are we, the Catholic Church, being for the state?

In focusing so much on how our faith obliges us to work for justice in the public sphere, I fear that we forget that there’s still a lot of work to be done in truly achieving justice within the Church.

The Church, in both its history and teachings, has failed people of color, women and the LGBTQ community, among others. While the Church as a global institution is certainly not free from criticism, it is especially important for us in the United States to reckon with the Church’s history in America.

The Church’s relationship with people of color, especially black Americans, has been marred by the Church’s participation and consent in slavery and segregation. We know now that in 1838, Jesuit priests at Georgetown University saved the school from bankruptcy by selling 272 enslaved people who had previously been owned by Georgetown. Private Catholic schools and Catholic parishes were often segregated, according to NPR. These, among countless other examples, demonstrate the wrongdoings for which the Church must continue to atone.

In more recent history, the Church’s appalling mishandling of priests sexually abusing young children counts as another failing, and an especially tragic one. In its willful attempts to cover up these incidents, the Church failed to live out its own faith.

However, even our Catholic faith is imperfect in achieving justice for the marginalized, especially as the faith has been interpreted and distorted by human Church leaders. As King referenced in his address to our campus, Christian and Catholic leaders both ignored and reinterpreted Christianity to permit or even justify slavery.

In his recent work “Building a Bridge,” Father James Martin, S.J., has shown how Catholic teachings on sexuality continue to marginalize LGBTQ people, even LGBTQ Catholics in the Church. During a recent talk on our campus, Elizabeth Gandolfo, Ph.D., theologian, demonstrated how the Church’s teachings on sin and forgiveness place women in a particularly vulnerable state. In the association of sin with women and in that the sole authority to forgive sin lies with male priests who exercise power over their parishioners, Gandolfo argues, Church teaching both marginalizes women and subjects them to male authority in a particularly unjust way.

No institution is immune from creating injustice and inequity. Our Jesuit theology teaches us to look outward and work for justice in the world we observe, but it’s equally as important for us as a Church to reckon with our own missteps, both in our history and our faith. I hope that during our reflections on King’s message to us 50 years ago, we also take the time to look inward and address the scars in our own institution and history as a Church.