Opioids claim life of 25-year-old Philadelphian

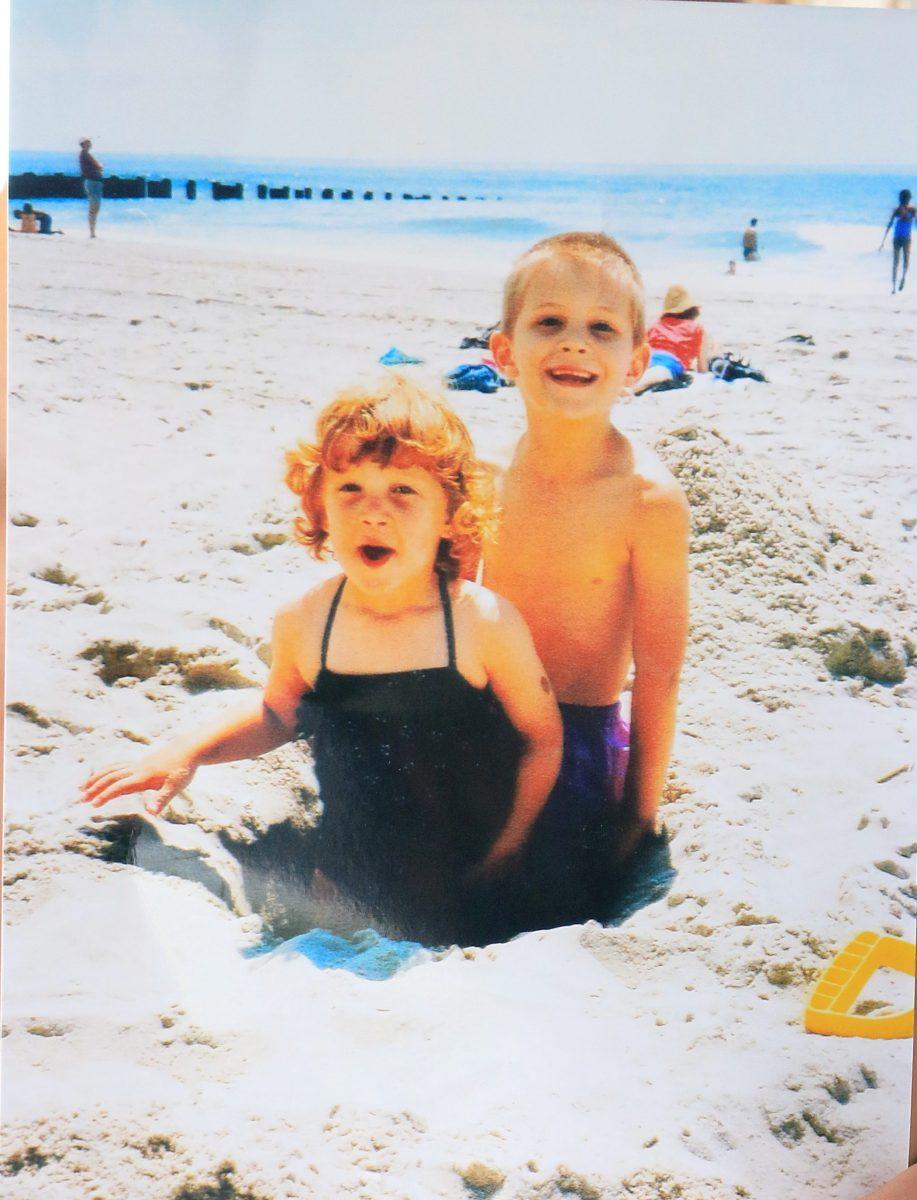

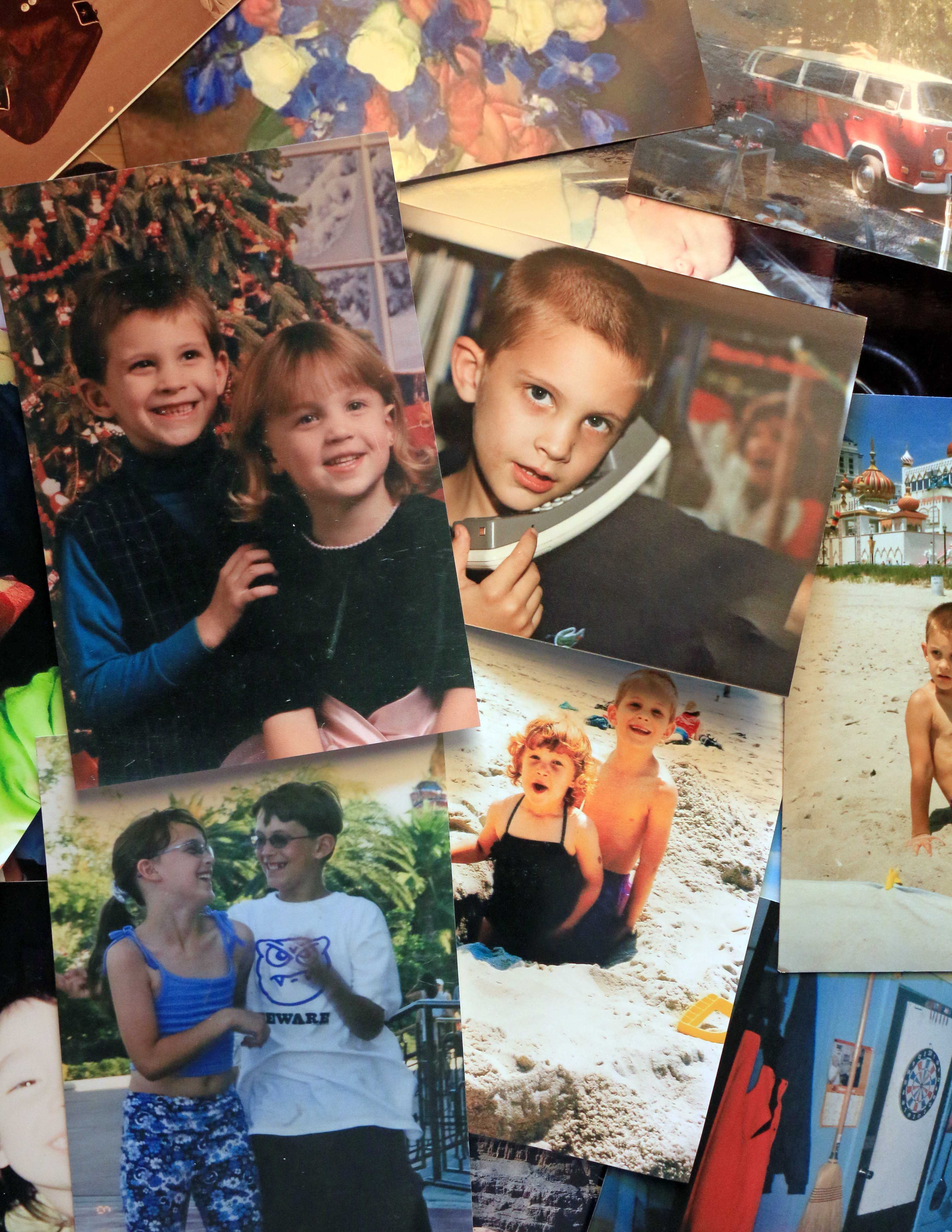

Jena Peters lives in the hills of Roxborough, a neighborhood northwest of Center City that runs along the Schuylkill in Philadelphia. The 24-year-old, who enjoys hiking, kayaking and venturing off into the nearby woods with her dog Zoey, grew up in Roxborough with her brother Zachary Peters.

It’s hard for Jena Peters to describe the kind of kid Zack was growing up, or even what he was like as a teenager. Mostly she remembers him getting high from the time he turned 13. Two years younger than Zack, Peters never considered her big brother a bad kid, but she didn’t consider him a good one, either.

As a teenager, Zack’s first run-in with drugs came in the form of marijuana. As he grew older, Zack began to struggle in school, where he simply “fell into the wrong crowd,” Peters said. Eventually Zack dropped out of high school. That’s when, according to Peters, “shit went south real fast.” He began distancing himself from his sister. When the siblings did talk, Zack shared fun stories from his drug-fueled escapades, without mentioning the drugs.

Before his death from a heroin overdose in 2017 at the age of 25, Zack sought treatment for his substance abuse disorder. With aid from his sister and mother, Zack entered nine different recovery programs across the nation between the years 2012 and 2017.

Zack’s cross-country rehab road trip over the years became the butt of many jokes between Peters and their mother.

“‘I should just become a drug user just so I can travel,’” Peters remembered joking.

Peters believes a lot of Zack’s problems stemmed from their rough upbringing, particularly alleged abuse at the hands of their father. Their mother Vicky Peters played an active role in her children’s lives, Peters said. The siblings also relied on their mother’s father, whom they called “Dziadziu,” the Polish word for grandfather. Dziadziu died when Jena Peters was 8 and Zack 10. Who is to say, Peters wondered, what their lives would have been like if Dziadziu lived longer to see Zack and Peters grow up? Perhaps he could have been there to keep Zack from going down the road that would ultimately lead to his death.

As Zack shifted from marijuana to pills to cheaper heroin, he became secretive and aggressive, “more of a dick,” really, Peters recalled. One time, in the early stages of his drug use, Peters discovered her brother had begun smoking cigarettes. This was before Peters herself began smoking, so she was concerned for her brother. When Zack left the house one day, she grabbed his pack of cigarettes and glued them all together. Peters then placed the cigarettes back in the pack and waited to see Zack’s reaction when he returned home.

“He beat the fuck out of me,” Peters recalled.

In addition to his mood swings, Zack also began taking part in criminal activity in the neighborhood. At first, he committed small offenses, such as defacing public property with graffiti, but he eventually moved on to more serious crimes with harsher punishments. He was arrested, locked up, and charged with possession of narcotics and drug paraphernalia on a few occasions. The cost of these crimes varied from fines to community service, and some jail time once he was a repeat offender. Zack also began stealing to fuel his substance abuse disorder. At first, he started small. He stole money from his girlfriend, as well as from his mother. He also stole from Peters, pawning her high school class ring and her iPad. He stole several jerseys worth about $10,000 from his father’s sports memorabilia collection. Another time he teamed up with a buddy to rob his neighbors’ house when the neighbors were away for the weekend.

When Zack stole Peters’ jewelry and iPad, she demanded he return them. She did not care how he

did it or why. She just wanted her things back. At first Zack said he had “no idea” what had happened to them. Then he blamed the theft on a friend. Then he confessed but said he would get the items back.

“It was a lie on top of lie on top of lie,” Peters said.

With every lie Zack told and every crime he committed, Peters found her brother was turning into someone she no longer recognized. One evening, while Peters was lying on the couch and her parents were asleep upstairs, Zack came home high.

“He was all types of fucked up. I don’t even know what the hell he was on,” Peters remembered.

Zachary stood in the family room in a daze, Peters recalled. It was like a different person had taken control of him. Peters attempted to speak to Zack to see what was wrong with him, but, like a phone ringing off the hook, there was no response on the other end.

Another night, after being out late, Zack came home, went straight up the stairs to the second floor of the Peters’ home, and headed for their parents’ room. Without saying a word, he opened the door, walked up to the bed and placed a knife to his father’s neck. This action threw the house into a panic, and Vicky Peters called the police. Burned into Peters’s memory is her brother screaming, “I will straight up fucking kill you,” while holding the knife to their father’s neck. The police arrived shortly after and, as Peters put it, “302’d his ass on the spot.” A code 302 is issued when a person is a danger to themselves or to others and is in need of medical or psychiatric help.

Shortly after that incident, Zack moved out. Once he was out of the house, Zack’s drug use worsened—although it was hard for Peters and her mother to monitor just how bad the problem was. During these years Zack spent living at his girlfriend’s house, he occasionally stopped by his childhood home to bum some money off his mother, telling her that it was for food, for the bus to get to work, for a promising job interview or just a pack of cigarettes. Their mother, feeling guilty, coughed up a few dollars for him, Peters said. From time to time, Zack would ask Peters for money, too, or for a ride somewhere, usually to his dealer’s house. She always refused. Peters knew if she gave into his begging, she would only be enabling his drug abuse.

Still, at times, there were glimmers of hope. When he was not getting high or landing in jail, Zack would reach out to his mother for help, realizing his substance abuse disorder was getting the best of him. His mother would agree to help and send him off to a recovery center or help him join a 12-step program. After treatment, Zack would come out clean and attempt to rebuild his life. But soon, he would be back on the streets, looking to score some dope.

Peters grew up in the same household as Zack and said she understands why he would want to numb his demons. The “shit from childhood” was the main source of Zack’s problems, she believes. Peters attempted on many occasions to persuade Zack to see these problems as she did and deal with them in a different way, but he couldn’t, or wouldn’t or just didn’t.

In the last year of Zack’s life, the siblings began to reconnect. Zack was once more in recovery and taking Suboxone, a drug used to help users fight their dependency on other narcotics. The two talked on the phone more frequently and met occasionally for lunch or dinner to catch up.

In March of 2017, Zack had just gotten out of another recovery center. Once again, he was staying clean and healthy and trying to get his life back in order. Peters began to see a difference in her brother. All the treatments seemed to be working on Zack, who frequently mentioned he had a few promising job interviews the upcoming week, ones he was both excited and a bit nervous about. Maybe the hard work he had put into his recovery was paying off, Peters hoped.

“He just seemed like he was in good spirits,” Peters said.

On April 8, 2017, Peters called her brother while out walking Zoey. She called him twice with no answer, then called her mother to no avail either. As Peters continued into the woods with Zoey, her phone rang. It was Zack. Peters filled him in on a terrible argument she had just had with their father. Zack didn’t say much but told Peters to meet him outside the house. He said he would be over shortly.

When Peters arrived at the house, Zack was outside waiting for her. The two walked up the stairs to the porch, swung open the front door and went inside. As they entered, their father was coming up the basement stairs. Zack began screaming at his father, telling him to never speak to Peters nor acknowledge her presence ever again. As Zack continued to argue with their father, Peters went outside. Moments later, the shouting ended, and Zack exited the house. As Zack walked off the porch and down the steps, he looked at Peters and said, “He won’t bother you again.” The siblings hugged, said their goodbyes and parted ways.

Around 10 p.m. Peters had just settled in for the night and started to watch a movie on Netflix. Suddenly, her bedroom door swung open. It was her mother. Tears rolled down Vicky Peters’ face as she broke the news that Zack had overdosed. The two threw shoes on, and, in a matter of seconds, were in the car speeding to Zack’s girlfriend’s house.

When they arrived at the house, the police and paramedics were already there. Walking up to the front door, Peters thought to herself, “They are going to bring my brother out in a fucking body bag.” Her mother informed an officer who they were, and the officer escorted them inside the house. They entered the kitchen and sat down at the table as the officer relayed what had happened.

Zack and his girlfriend had tucked in for the night to watch a movie, Peters remembered the officer told them. After making popcorn and grabbing a few extra blankets, Zack told his girlfriend he had to use the bathroom and would be right back. He was in the bathroom for an unusually long time, so his girlfriend called up to him. There was no response. She paused the movie and went upstairs to check on him. She knocked on the door. There was no response. Fearing that something was wrong, his girlfriend opened the bathroom door and found him lying on his back, naked, in the bathroom. A needle was still in his arm. His girlfriend called Zack’s mother, then dialed 911. Although the paramedics attempted to revive Zack with several doses of Narcan, Zack was pronounced dead at the scene. Cause of death: heroin overdose. Zachary Peters, boyfriend, son, brother, had become a statistic, one of 1,200 deaths from drug overdoses in Philadelphia in 2017, according to estimates from the Mayor’s Opioid Task Force.

At some point earlier on the day he died, Zack had sent a text to his dealer to negotiate the purchase of three bags of heroin, Peters later learned. There might have been a multitude of reasons why Zack felt the need to get high that night. The fight with his father might have sent him over the edge. Or maybe his depression had resurfaced. Perhaps the pull of his disorder had just been too strong. Not knowing the answer is the hardest part for her, Peters said.

“We’ll never know if it was an accident or if it was on purpose,” she said. “I think that’s the part that kills me the most.”

When Zack was younger, he had a dog named Moose, an Akita Mix that he came home with one day. Zack probably stole him, Peters said, but what was clear was how much Zack loved that dog. As Moose grew older, his eyesight began to deteriorate, and he had trouble walking around the house. Eventually Moose died, devastating the Peters siblings. Shortly after Moose’s death, the dog appeared to Peters in a dream. In the dream, Moose ran around an open field, jumping, barking, rolling around in the grass. The dog seemed happy and healthy, a sign to Peters that Moose was in a better place.

“In my head, that was his way of telling me he was okay,” Peters said. “What happened was supposed to happen. Now, I keep waiting for Zack to come to me in a dream.”

So far, that hasn’t happened. But when he does, Peters said, she will know her brother is in a better place and everything will be okay again.