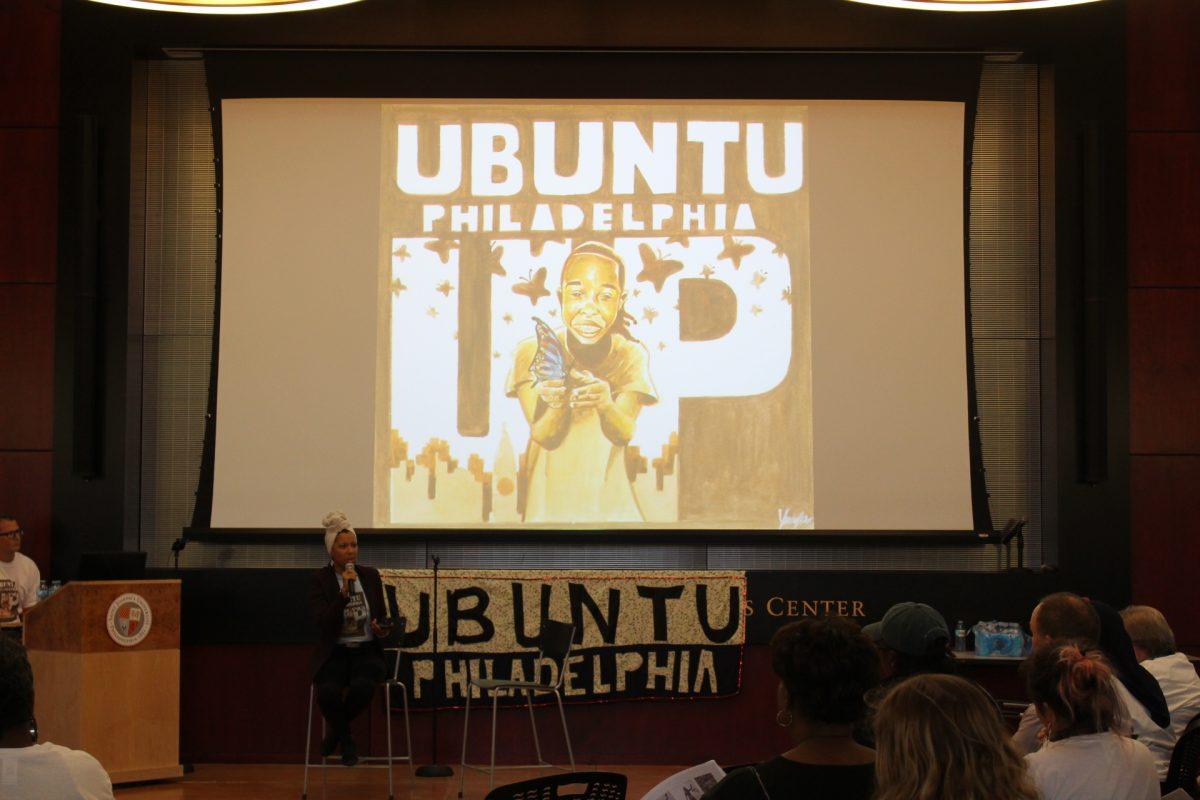

Ubuntu Philadelphia returns to St. Joe’s

Ubuntu Philadelphia hosted its second public forum on community violence in the Cardinal Foley Center on Sept. 8.

The event, founded by Rosalind Pichardo, founder of Operation Save Our City and Kempis “Ghani” Songster, a recently released “juvenile-lifer,” was organized by J. Michael Lyons, Ph.D. and Susan Clampet-Lundquist, Ph.D., to promote the message of healing from violence through community and love.

“To be able to partner up is something that’s about finding common cause and building community,” Songster said. “That’s something that you don’t see too often in this society and I think that kind of relationship, this kind of conversation we had today, is what’s going to be important to our society moving forward.”

Although it cannot be completely translated into English, the Bantu word “ubuntu” essentially means “humanity” or “I am because you are.”

This word is reflected in the forum’s mission: to change a culture which breeds violence by creating a space for open discussion, Songster said.

“The reason why this conversation is important to me is that I don’t think it’s a conversation that’s being had,” Songster said.

Throughout the event, volunteers called “Care Bears” were stationed around the edges of the room in order to provide emotional support and resources for people who might be affected by the material being discussed.

The name “Care Bear” was chosen to convey openness and comfort, according to Fernando Sterling, a Care Bear and victim advocate for the city of Philadelphia.

“It’s just something we agreed on,” Sterling said. “It exemplifies what we’re here for, we’re here to care for anybody that needs any type of help or emotional support.”

The forum, which began at 12:30 p.m. and ran until 6:00 p.m., opened with a brief skit performed by the T.U.F.F. Girls and El Centro High School. After a reflection on the popular image of Lady Justice, Songster held a panel discussion with radio producer Samantha Broun on her podcast “Living With Murder.”

Broun, whose mother survived a horrific attack by a man who had been released from a life sentence he had received as a juvenile, explained that she “was full of anger and fear” afterward.

After seeing the perpetrator, Reginald McFadden, in court, Broun considered her intense feelings of anger.

“I have that violence and fear in me, too,” Broun said during the panel. “If I could feel those feelings of violence, could he come away from those feelings of violence?”

During the discussion, Songster said that one of the reasons he believes young people commit such horrific crimes is their poor self-image.

“The majority of people that [are] overly represented in prison systems are people of color,” Songster said. “I’ve met so many people of color that just don’t feel good about themselves because they’ve never been taught in schools to feel proud of themselves. They’re referred to in society as thugs, as super-predators, all kinds of things that are so debasing.”

Mari Morales-Williams, who mediated the panel, said the belief and investment in restorative justice she shares with Songster has been a significant part of her own healing.

“It’s been my commitment to more fully realize what that can look like in our society where there’s a dominant narrative that the only way we can arrive at justice is through police and prisons,” Morales-Williams said.

Following the panel, Songster and a group of other “juvenile-lifers” delivered a public apology, with each man stating his crime and his remorse.

Harry King, one of the men giving an apology, said that the aftereffects of violent crime were like a crumpled piece of paper.

“No matter how long you smooth that paper out,” King said, “it will never be the same.”

To Pichardo, the forum was “perfect.”

“It was perfect in a sense that I finally got to hear what I needed to hear from people who’ve committed the ultimate crime,” Pichardo said

Joshua Glenn, co-founder of the Youth Art and Self-Empowerment Project, attended the event to learn about different ways to heal from violence.

“I think that we rely on our oppressor to change our conditions,” Glenn said. “And so, for me, learning how to heal and how to heal our communities, that’s key to making change.”