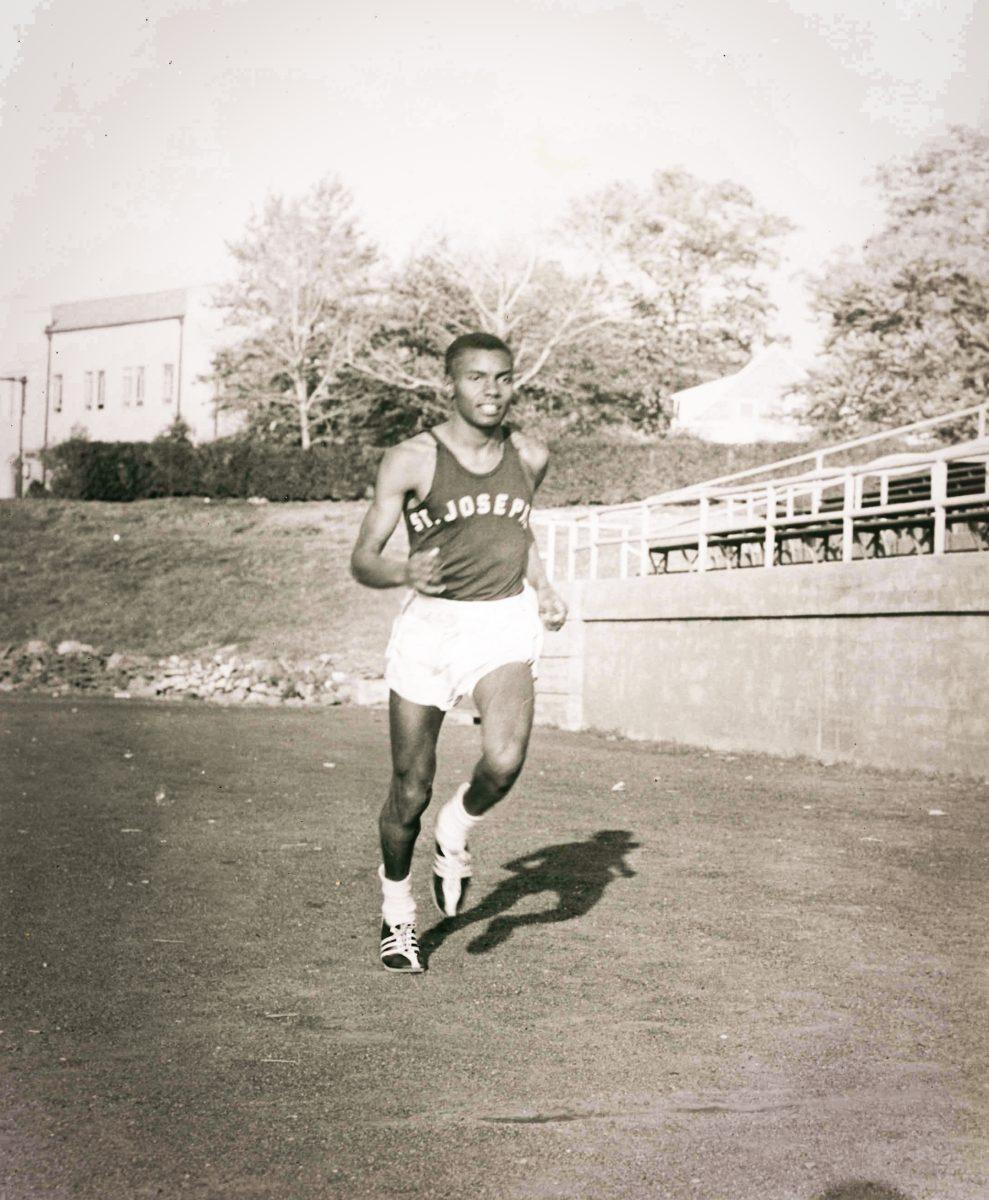

While St. Joe’s has fielded athletic teams since at least the early 20th century, not until the 1950s did the first athlete of color represent the university in an athletic competition.

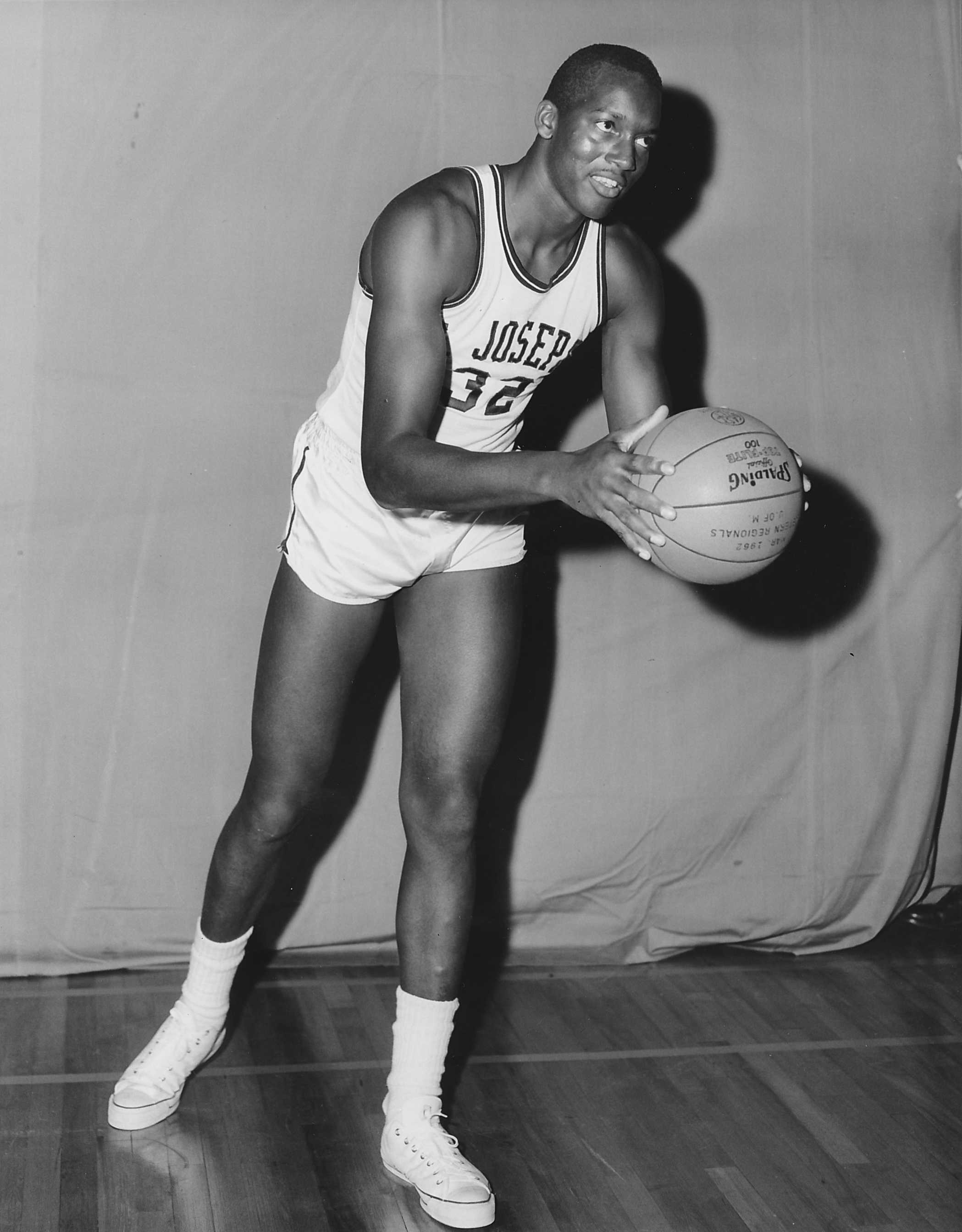

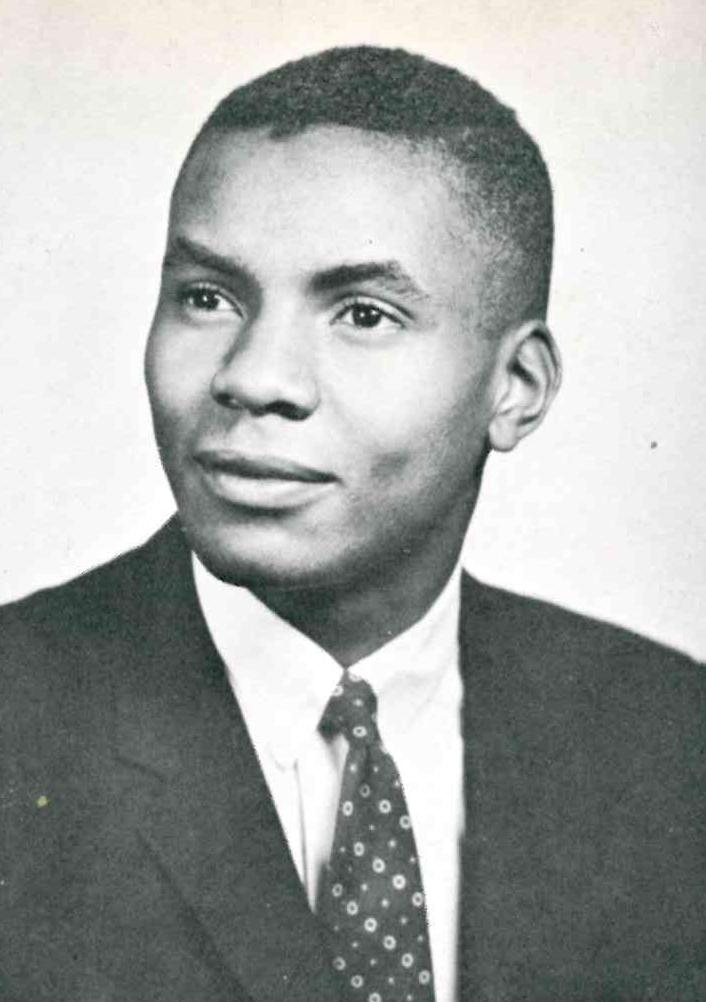

Dick Adams ’59, a long jumper, competed as a member of the St. Joe’s track and field team. Several years later, John Tiller ’64 became the first black basketball player on Hawk Hill, according to Don DiJulia ’67, former director of athletics and a teammate of Tiller.

Adams and Tiller played for St. Joe’s during two turbulent decades in U.S. history, according to Jamal Ratchford, Ph.D., an assistant professor of history at Colorado College who studies the role of black athletes in sports. Those decades also saw more interracial sports teams on college campuses.

“There was scientific racism nationwide during that era,” Ratchford said. “You need to put the role of the black athletes, at least intercollegiately, in that broader national context that was happening all over the country.”

The same year that Tiller graduated from St. Joe’s, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, with the intention of prohibiting segregation in public places and banning employment discrimination.

“Just because a law was passed didn’t mean people abided by that law,” Ratchford said. “This imaginary of the North that we think of as inclusive isn’t always true. You have to think in terms of lived experiences. Yes, you might have had X, Y, Z black athletes at St. Joe’s, but what were their lived experiences?”

Tiller and Adams are unable to share their firsthand accounts, however. Tiller died of cancer in 2012. Teammates and friends of Adams haven’t seen or heard from him since a team reunion about 10 years ago, according to Jim Gavaghan ’58, a track and field teammate who has kept in touch with a network of fellow classmates.

But Tiller and Adams’ teammates said they don’t remember any overt discrimination at St. Joe’s, at least from fellow teammates.

Tiller was looked at with the same respect as other players on the team, according to DiJulia, partially because the vast majority of athletes and students at St. Joe’s were from the Philadelphia area. Many of Tiller’s basketball teammates were already familiar with him from his time at La Salle College High School, DiJulia said.

“Philadelphia being so neighborhoodish, everybody knew each other, so people who came here in the freshman class, they knew who John Tiller was,” DiJulia said. “We never felt any tension here.”

Adams also hailed from Philadelphia and attended West Catholic High School, which produced three other athletes on the St. Joe’s track and field team during Adams’ tenure.

Road games were a different story, though, according to DiJulia. The team once had to switch hotels when playing Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina because of the hostility still present in the South towards black people.

Kevin Quinn ’62, who coached the men’s and women’s track and field teams for a total of 49 years and was a teammate of Adams, said he doesn’t recall any discrimination or controversy towards Adams.

“I don’t think anyone else on the team saw him as any different than any of our other teammates,” Quinn said. “He was just a member of the team.”

Quinn acknowledged, though, that the team didn’t discuss Adams’ experiences as a person of color.

“It wasn’t something really that we talked about particularly,” he said.

Adams also was one of only a handful of black athletes on the track and field team during the 1970s.

“It was for no particular reason other than we just didn’t have them,” Quinn said. “It certainly wasn’t a conscious attempt not to have them.”

Gavaghan also recalled a welcoming atmosphere within the track and field team. However, he remembered Adams recounting a discriminatory incident away from the track during his senior year at West Catholic.

“The only controversy he had [was] when he was in high school at a track meet,” Gavaghan said. “The guys went to play miniature golf, and the guy that was there would not let him play because he was African American.”

Quinn and Gavaghan, two Philadelphia area natives themselves, also echoed DiJulia’s sentiment about the tight-knit Philadelphia high school athletic community factoring into the two athletes’ general acceptance at St. Joe’s. Adams was also known on campus for more than his contributions to the track team.

“He was just a congenial, wonderful fellow, quite an athlete and a great teammate,” Gavaghan said. “Dick was a number of other things other than just track. He was involved in a lot of activities on campus and was respected by everyone that was in them. He was a talented young man.”

Not only were Adams and Tiller both Philadelphia-area natives before college, but their paths after St. Joe’s were similar as well, both serving their country in different ways. Adams was a member of the Air Force ROTC in college. Tiller became a close aide to former President Ronald Reagan as a deputy special assistant to the president and associate director of the Office of Public Liaison.

“He was a salt of the earth guy,” DiJulia said of Tiller. “Quiet demeanor, really sharp and just a wonderful man.”

There is no mention of Adams and Tiller’s status as two of the university’s first black athletes in the university archives, according to Chris Dixon, archival research librarian. One reason for this, he suggested, may be due in part to the lack of controversy surrounding interracial teams at St. Joe’s, as Adams and Tiller’s teammates alluded to.

“It may not necessarily have been recognized as a big deal at the time,” Dixon said. “We have to look at it in terms of what was captured, not necessarily what was actually happening at the time. There have been team photos, but it’s not necessarily something that has been researched, and it’s not part of something that we’ve traditionally seen.”

That was the experience for Mike Thomas ’78, a black athlete on the basketball team between 1974 and 1978. Thomas said he wasn’t subjected to any race-based prejudice during his time at St. Joe’s.

“During my college years at Saint Joseph’s, I didn’t experience any form of racism in the dorms, in class or on the court,” Thomas said.

For Ratchford, though, discrimination in sports is an ongoing issue. He is hesitant to use the term integration because he does not think sports are completely integrated to this day.

“I’m hesitant to use a word that I don’t think we understand,” Ratchford said. “We like these assumptions, and we like these neat packaged stories as Americans, and I don’t think we investigate the ugly side of the story.”

Ratchford said he holds out hope that the actions of men like Tiller and Adams will ultimately be looked at the beginnings of true integration.

“I’m an optimist, and I have some of that American optimism too, and I think we can still be better than what we are,” Ratchford said.