Taking a closer look at St. Joe’s Clery Act sexual assault statistics

According to the Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network (RAINN), 23.1 percent of female college students and 5.4 percent of male college students will experience sexual assault during their four years of undergraduate education.

The Clery Act, a national law to prevent campus crime, mandates that all colleges and universities report the statistics of campus crime, including sexual assault and rape. The report is released annually on Oct. 1 of the following year by colleges and universities nationwide.

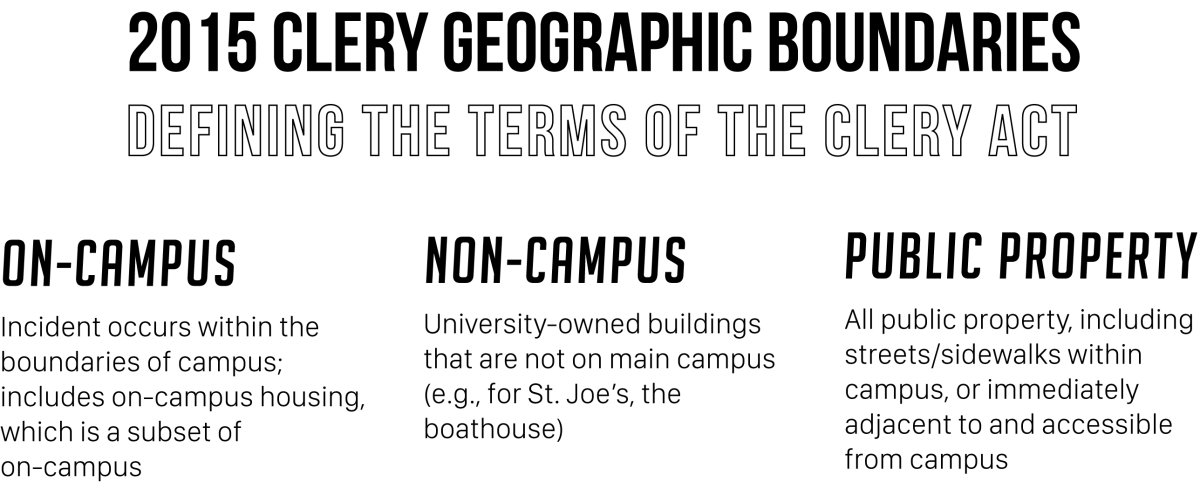

According to Kiersten White, Ph.D., assistant vice president for Student Life, the Clery Act consists of three locations universities must report.

“The Clery Act focuses on reporting of campus crime statistics in very specific geographic categories,” White said. “There are four categories, one is a subset of another: On-campus (a subset of that is residence halls), non-campus [university-owned buildings that are not on main campus], and public property. So there are four very specific geographic locations defined by the Clery Act; institutions then look at the definitions of those geographic locations, and apply it to their own campuses.”

Saint Joseph’s University’s Annual Security Report and Annual Fire Safety Report (the university’s annual report of its Clery statistics) states that, during the 2015 calendar year, two instances of rape occurred in on-campus housing, one instance of fondling occurred on-campus, one instance of dating violence occurred in on-campus housing, and four incidents of stalking occurred on-campus (three occurred on-campus, and one in on-campus housing).

The Clery Handbook, available through the Clery Center to aid universities in figuring out their geographic boundaries for reporting, defines public property as, “all public property, including thoroughfares, streets, sidewalks, and parking facilities, that is within the campus, or immediately adjacent to and accessible from the campus.”

The Handbook requires campuses to report crimes committed on the road that is immediately adjacent to campus, as well as the sidewalk on the opposite side of the road.

“What that leaves out is our typical off-campus houses and apartments where students reside,” White said. “So that off-campus geographic location is not always captured in the Clery Act statistics. So, public property captures some of that, but that’s really talking about what’s around campus, not necessarily Manayunk or Roxborough or 63rd St.”

The geographic parameters of the Clery Act mean that incidents that occur in areas where students typically live – for example, on 63rd Street, in Manayunk, or even just a few blocks from campus – are not included in the annual report.

The Clery Act, signed in 1990, is named for Jeanne Clery, a student of Lehigh University who was raped and murdered in 1986 by a fellow student who she didn’t know. The act, which resulted from efforts by her family, is enforced by the Department of Education, and covers campus crimes, including liquor law violations and more violent crimes like murder, domestic violence, and sexual assault.

However, since the geographic locations are so strictly defined by the law that means that, as a result of the strict definitions of the Clery Act, some instances of assault or rape that do occur are not listed in the report.

“You see the [statistics], and say, ‘Wait, there must be more [incidents],’ and there are, typically, because it’s not in that area that Clery defines,” White said. “There are more reports; we may receive a report of a sexual assault that happens in an off-campus house or somewhere not defined by Clery.”

Mary-Elaine Perry, Ph.D., Title IX coordinator and assistant vice president for Student Development, echoed White’s statement, saying that instances of sexual assault or rape occur off-campus, and are, therefore, not covered under the parameters of the Clery Act.

“The other piece of it is, a lot of students don’t report,” Perry said. “Maybe they don’t know who the person is that assaulted them, or maybe they do know, and they don’t want to get that person in trouble, and I’ve heard that many times, ‘I don’t want to get him in trouble.’ More often than not, it will be a male perpetrator.”

According to RAINN, only 20 percent of female student survivors of sexual assault report incidents of assault to law enforcement. The organization states that the remaining 80 percent of women do not report sexual assault for several reasons, including the belief that police would not or could not help, the belief that the incident was “not important enough” to report, or, as Perry said, the desire not to get the perpetrator in trouble.

White also stated that the United States Department of Education, in conjunction with the Clery Act, is very clear about what should and shouldn’t be included in colleges’ and universities’ annual reports.

“They’re clear about not adding those numbers [of off-campus incidents] into your Clery report, because that’s not how the law is defined,” White said. “Adding different reports into those numbers can confuse people. And so, really, the annual security report is in place to help people become aware. It’s an educational opportunity, and the last thing we want to do is conflate some of that information.”

Abigail Boyer, M.S., is the associate director of programs at the Clery Center, located in Wayne, Pa. She said that the Clery Center trains institutions in order to avoid mis-reporting data, and that one of the organization’s primary goals is to help institutions create environments in which people would feel comfortable reporting incidents. She said that some of the challenges that may lead to misreporting include a lack of training for responsible employees, or a misunderstanding of what incidents must be reported.

“The Department of Education enforces the Clery Act,” Boyer said. “If the Department finds an institution to be out of compliance, there can be fines of up to $35,000 per violation.”

Boyer said that as a result of the Clery Center’s training, it is less likely that institutions will misreport data. According to Boyer, it is the Clery Center’s hope that this training will help survivors feel more comfortable reporting incidents to campus authorities. The training includes discussion of the restrictions of the Clery Act, and provides institutions with resources to help survivors.

“A survivor may not want others to know about their experience, or have concerns or confusion about what to expect when reporting to police or to a campus official,” Boyer said. “Sometimes they may not know that certain reporting options even exist, so it’s important for institutions to proactively communicate about the resources and reporting options available to survivors on campus.”

Perry stated that there are still options for survivors who choose not to report the incidents to authorities. Aid can still be provided to survivors by several campus organizations, including the Rape Education and Prevention Program (REPP) and Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS).

“The counseling center is completely confidential,” Perry said. “They can certainly take advantage of what we offer to all students; they can contact REPP and get assistance through REPP by working with Dr. Bergen [Raquel Kennedy Bergen, Ph.D., sociology professor and director of gender studies], they can certainly work with the counseling center, and there are community resources as well.”

Perry listed the benefits to reporting an incident, many of which include support from the university. She said that, if there is knowledge of the incident, accommodations can be made to ensure that the survivor does not have to interact with the perpetrator, whether that includes having someone switch classes or residence halls, or placing contact restrictions.

These accommodations are available to all students who report incidents, regardless of whether or not the student decides to pursue a case against the offender.