Is it constitutional?

This week began the second impeachment trial of former U.S. President Donald Trump. On Jan. 6, the country watched in horror as Trump supporters stormed the U.S. Capitol in an attempt to stop proceedings certifying U.S. President Joe Biden as the winner of the presidential election.

The mob that stormed the Capitol was incited by a speech that Trump made earlier in the day, in which he continued to make false claims of election fraud. The chaos that ensued afterwards threw the country into an unprecedented situation, in which Congress took steps to impeach Trump for a second time and remove him from office with only two weeks left in his term.

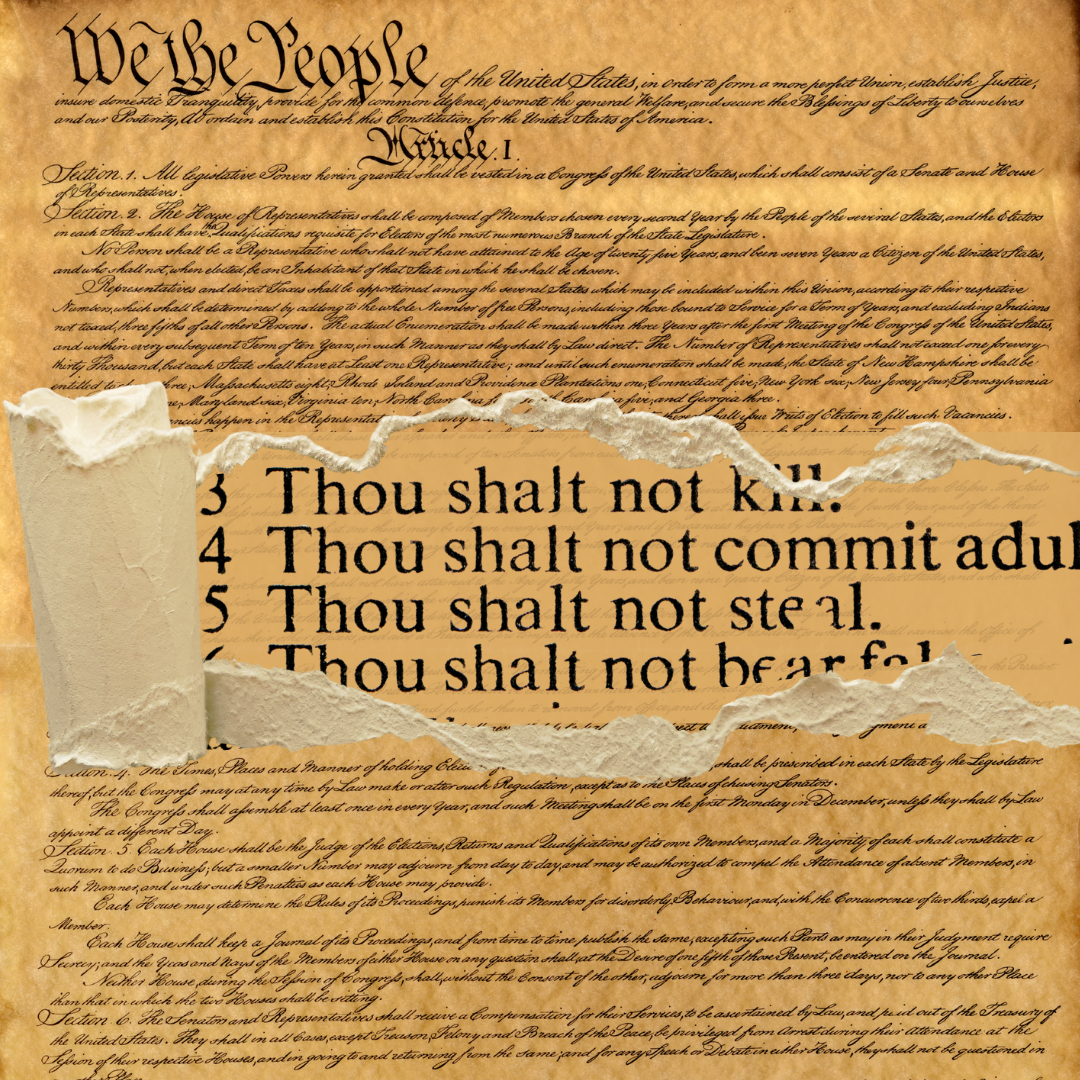

Now that Biden is in office and Trump is officially a private citizen, the question has become whether or not it is constitutional to convict a former president in an impeachment trial.

While the debate over this issue is far from settled, I would argue that it is constitutional to impeach and convict a former president. My conclusion is based on three important concepts: historical precedent, the words of the Constitution itself and the necessity of preventing lame-duck presidents from committing crimes during their last days in office.

The concept of post-term impeachment is not unique to our time. Twice in the Senate history has this question been brought up. The first was during the impeachment of Senator William Blount in 1797. The second was during the impeachment of Secretary of War William Belknap in 1876, a case which is more relevant to the current impeachment. In that case, Belknap was acquitted because the Senate did not reach the two-thirds majority necessary for conviction, but prior to the trial’s proceedings, the Senate convened and agreed that they were constitutionally empowered to preside over impeachment trials of former government officials.

While there are no examples of former officials being convicted during their impeachment trials, the Belknap case shows that the act of impeaching a former government official has never been off the table. However, historical precedent can only take us so far. Those against impeaching former officials would be valid in mentioning the fact that this question was just as controversial in the 1870s as it is today. Many senators who voted for acquittal in the Belknap case did so because they believed that the Senate did not have the power to convict a former official. That conclusion was not a definitive condemnation of the idea that a former government official could be impeached, especially considering that a majority of senators voted to convict Belknap.

This is why I believe that, in conjunction with historical examples, it is important to consider both the text of the Constitution and the intent of the framers of the Constitution in including the provision on impeachment in the Constitution.

In a letter written by an ideologically diverse group of 150 lawyers, the group argues that the Constitution allows for the impeachment of former government officeholders because of the two aspects of impeachment contained within the Constitution: removal from office and disqualification from running for office in the future. Both concepts, the scholars argue, are distinct from one another within the text, meaning that the latter aspect is not solely dependent on the former.

The scholars further assert that the text itself does not prevent the impeachment of former officials, as there is nothing written in the Constitution that advocates for or against this action. Obviously, the ambiguity of the Constitution on this issue is the reason why this debate has been prolonged for so many years, but the fact is that there is nothing within the text that prohibits this kind of impeachment.

More important to consider is the intention of the framers in crafting the impeachment section of the Constitution. As constitutional scholars point out, the framers based much of their understanding of impeachment on its use in British law at the time, which did allow for impeachment of former government officials.

The framers intended for impeachment to be the means by which Congress could prevent tyrannical abuses of power from harming the republic. Neither the tyrant nor his ability to disrupt are nullified after his removal from office, which is why the framers included the provision on disqualification from holding future office.

The question ultimately becomes that if the Constitution does not allow for former officials to be tried and convicted in an impeachment trial, then what is the recourse for punishment of politicians who use their office to commit crimes during their last moments in office?

It would be nonsensical to allow politicians the right to escape punishment for crimes because they waited until the right moment to commit them. Our Constitution is too strong to allow this kind of loophole to exist, which is why I believe that Trump’s impeachment trial is within the rights of constitutionality.