As efforts to ban books in schools spread across the U.S., current and former education students at St. Joe’s are considering how these challenges impact their choices in the classroom.

“People dream about being teachers and being able to influence students and their education, even on a small scale,” said Ally Craskey ’23, an English and secondary education major with an educational studies minor. “It’s really upsetting to not be able to do that or to have a fear around doing that.”

The American Library Association (ALA) tracks books that have been challenged or banned. According to the ALA, challenging a book is an “attempt to remove or restrict materials, based upon the objections of a person or group” while a ban is the formal “removal of those materials.”

As listed on the ALA website, the top three reasons for challenged books are due to “sexually explicit” material, “offensive language,” or material “unsuited to any age group.” Many of these books contain content related to race, gender and antisemitism, and many are written by Black authors.

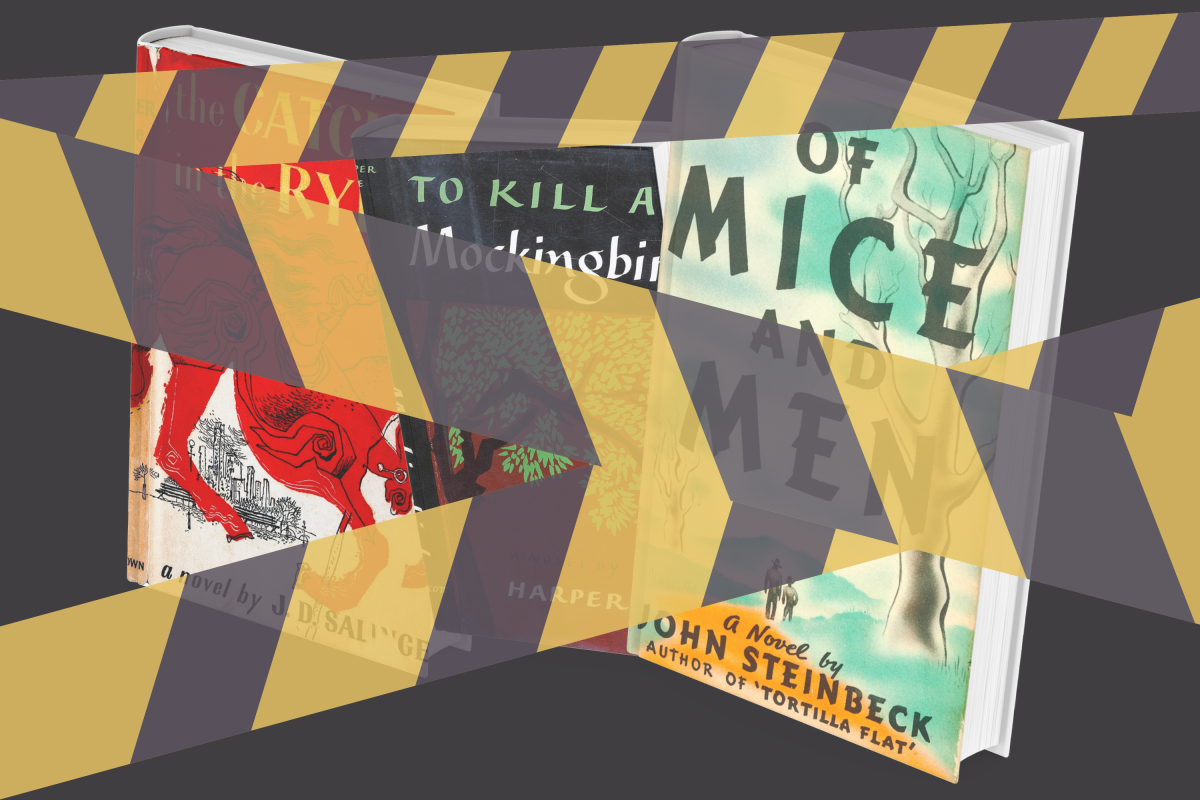

The list includes books such as “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee, “Of Mice and Men” by John Steinbeck, “The Catcher in the Rye” by J.D. Salinger, “Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out” by Susan Kuklin and “George” by Alex Gino.

Jaulie Cantave ’22, a student teacher in the English department at Belmont Charter High School in Philadelphia, said banning books encroaches on First Amendment rights.

“If we’re banning books, then we’re limiting the students’ ability to make their own decisions, and their ability to be critical thinkers. And we’re also limiting their worldview,” Cantave said.

Moreover, book bans hurt students from marginalized groups the most, Craskey said.

“Words have power, and telling stories has power,” Craskey said. “So censoring those stories and taking power away just re-centers it to the dominant narrative.”

It is important for students to see themselves in the books they read, Craskey said.

“Representation is so important, and there’s already so many books about white people and men,” Craskey said. “And it’s not to say that those students don’t deserve to feel represented, but it’s about equity.”

One of the books that is on the ALA’s list is “Giovanni’s Room” by James Baldwin. The book focuses on a complex exploration of one’s sexuality and gender identity. Thomas Brennan, S.J., associate professor and chair of the English department, said he does not understand objections to the book.

“It’s stupid even to say it has a ‘graphic description,’” Brennan said. “And so what if it does? I think that’s secondary to the fact that the book is talking about a very, very human reality both of understanding one’s identity as gay and also being closeted and recognizing that. Never mind that Baldwin is an author of color, writing this from the perspective of somebody at the time living outside of the United States.”

Christina Photiades ’20, a middle school English teacher in the greater Philadelphia area, said censoring children from real-world problems is a disservice to them.

“The very ironic thing about banned books is that it actually draws more attention to specific books,” Photiades said. “We all know that when you tell a little kid not to take a piece of candy, they’re going to want that piece of candy even more than they did before.”

Photiades said nobody has yet objected to her curriculum, and that these efforts to ban books often depend on where someone teaches and whether their place of employment is a public, private or charter school.

Nick Mandarano ’18, who taught at a Lansdale Catholic High School before leaving to pursue a Ph.D., said teachers are frustrated and divided over these book bans and challenges.

“We’re always told, if you can’t change the world, change what’s around you, and now they can’t even change the 30 students in front of them or at least open their mind,” Mandarano said. “It’s frustrating, and I think a lot of teachers are forced to teach things they don’t necessarily believe, or forced not to teach things that they do believe.”

When it comes to helping future teachers navigate these issues, Althier Lazar, Ph.D., professor of teacher education, said teachers, administrators and parents need to band together to take a stand in defense of challenged books.

“If children and youth are denied access to these books, then we risk the possibility that they will remain ignorant about racism and will not be willing or able to challenge racial injustice,” Lazar said. “Not only should educational stakeholders take a stand on this issue, we also need to challenge bills like the Teaching Racial and Universal Equality Act, which will curb teachers’ use of literature and informational books that address systemic racism in the U.S., as well as how teachers can talk about issues of race.”

Photiades said it is also important for teachers to find staff in their school who support what they want to teach.

“I’m lucky enough to work closely with an incredible librarian who is so in tune with the students and what they are interested in reading, no matter the nature of the book,” Photiades said. “Finding administrators that will support you and your goals is huge, but finding ones that will have your back is even more important.”