Race and gender in the confirmation hearings of Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson

Last week’s raucous Senate spectacle centered on Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson’s identity, the first Black American woman to be nominated by an American president to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In all other ways, Judge Jackson is the typical presidential nominee for the Supreme Court. She is a graduate of an elite college and law school (Harvard) who worked as a corporate attorney before serving as a federal judge. A moderate who supports considering the “original” meaning of the Constitutional text, she has more experience than most members of the current Court. Her appointment leaves a 6-3 conservative majority intact. She looks like the typical candidate except for — the way she looks.

W.E.B. Du Bois wrote in 1903 that the “problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color line” and, in 2022, the issue of race is key to understanding the volume and content of these hearings.

We might be distracted by the political theater. Senators create a soundbite for their Instagram or national cable news. Parties build brands for the midterms and 2024 presidential elections. Republicans position themselves as law and order, pro-life defenders of the Constitution. Democrats model their commitment to a multi-racial democracy, the rule of law and traditional decorum threatened by Trumpism.

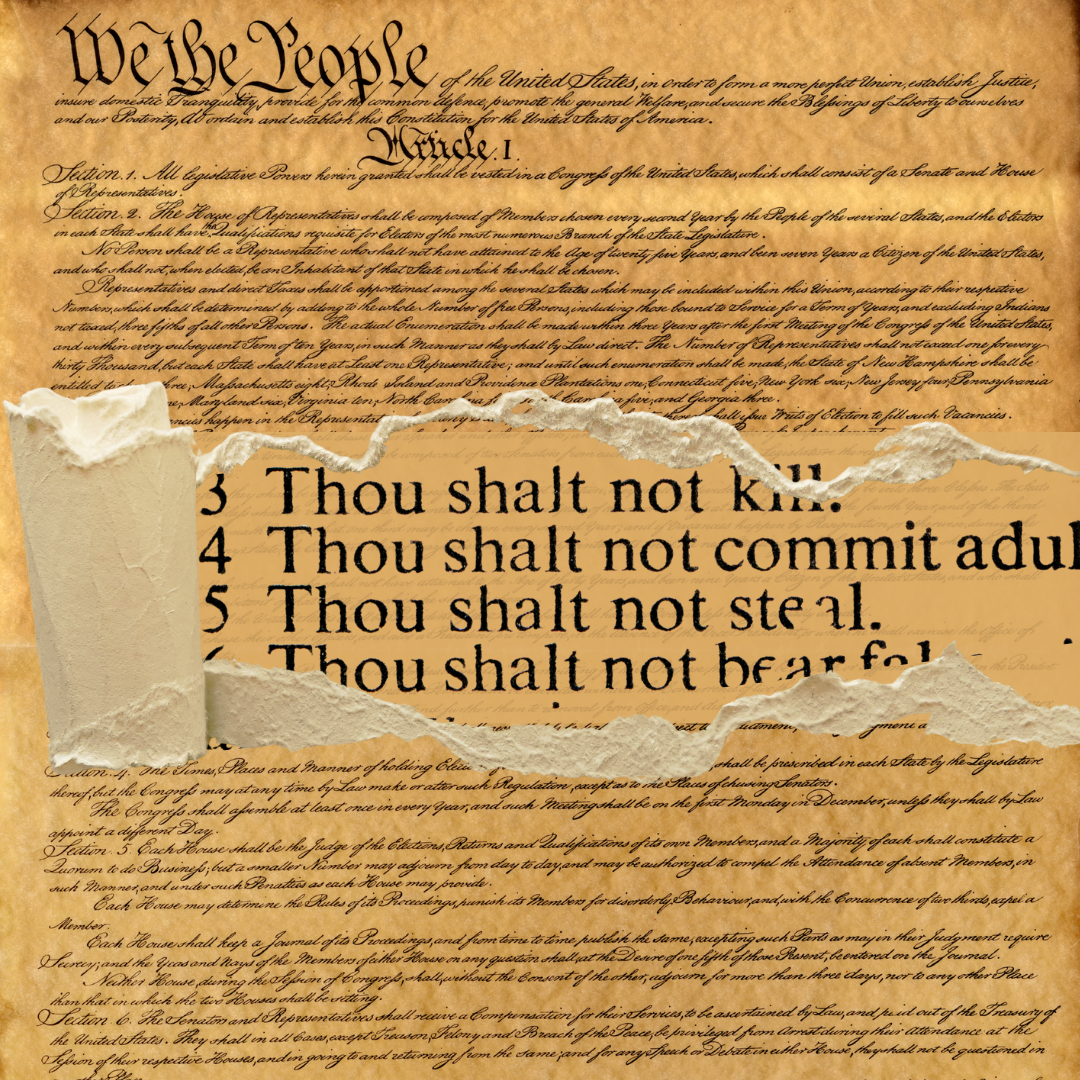

But a little history reveals how identity politics and racism motivate the most pointed questions from Republicans. Article 2, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution gives the Senate the power to “advise and consent” to the president’s nomination of justices of the Supreme Court. Until 1916, the Senate held (mostly) voice votes that approved the president’s pick. They never held hearings.

Most justices came from the East. Three Catholics had served, among them the notorious Roger B. Taney of the “Dred Scott” decision and Joseph McKenna, who attended Saint Joseph’s College. The President (white, male and Protestant) submitted a name (white, male and mostly Protestant). Hearings were unnecessary because senators assumed that a white, Christian identity equaled merit.

The practice of exclusively considering Christian, white men was broken when Woodrow Wilson nominated Louis Brandeis: a Jewish corporate lawyer who had transformed himself into the nation’s first public interest attorney, suing the corporations he once served. Open anti-semitism led to a hearing with witnesses (though Brandeis did not appear). When another Jewish American was nominated in 1939, the FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover called Felix Frankfurter a dangerous communist based on his defense of Sacco and Vanzetti (Italian immigrant anarchists who were later executed) in the “Atlantic.” Frankfurter appeared but always responded that his public record spoke for itself. He would add nothing.

In the case of Brandeis and Frankfurter, Jewish identity implied radical left ideology. Brandeis had worked on behalf of workers’ rights. Frankfurter had defended supposed traitors and founded the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

In a televised 21st century hearing, Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson endured days of questioning and Republican racial dog whistles that implied that Black Americans are criminals, soft on crime, unpatriotic and their qualifications are not earned through merit. Like Brandeis and Frankfurter, Jackson had to defend against racist stereotypes and the assumption that her race radically interrupts the ideological status quo.

The mention of the famous Willie Horton ad folded into all the questions about critical race theory and education. Rather than assume her neutrality, patriotism and merit, Judge Jackson had to prove it to the Senate Republicans. Her short service in public defense (two and a half years versus seven years of corporate law) led to pointed questions about her sentencing of consumers of child pornography and defense of detainees in Guantánamo Bay.

She patiently explained the facts over and over. Interrupted and mansplained, she remained poised and polite. She had to. Unlike Justice Kavanaugh, whose expression of anger and raised voice was coded as a spirited defense of his good name, Judge Jackson navigated between sexism (a raised voice is “shrill”) and racism (anger signals violence or “unearned superiority”). Political scientists call the latter an “anger gap.”

The hearings demonstrated the unspoken codes that privilege hegemonic groups — that transform “the judge” into “she,” as Senator Cruz said over and over while arguing for more time.

The name-calling, misinformation and stereotyping reflected our toxic politics — and the centrality of race. Despite the national self-analysis triggered by #BLM, a color (and gender) line remains.

Susan Liebell Ph.D. is the Dirk Warren ’50 Sesquicentennial Chair and a professor of political science.