Johannesburg, South Africa – When browsing the young adult section of Book Circle Capital, readers won’t come across J.K. Rowling’s “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone” or Suzanne Collins’ “The Hunger Games.” Instead, they’ll find books like Loyiso Mkize’s “Kwezi,” a graphic novel about a South African teen superhero who saves a city resembling Johannesburg, and Refiloe Moahloli’s “You are Loved,” a picture book about an African family celebrating intergenerational love.

Sewela Langeni, owner of Book Circle Capital, located in Melville, a suburb in Johannesburg, is part of a push among independent bookstore owners to get South African literary works in South African bookstores.

Langeni said little attention is given to South African authors in major chain stores across the country, which sell largely Eurocentric and other international books. This lack of representation, Langeni said, is a result of the country’s history of racial marginalization, which attempted to repress South African voices.

“Our history with apartheid and colonialism, unfortunately, also determined the type of books that were being sold,” Langeni said. “It’s a pity that some chains are not following because there’s been a whole movement to decolonize content that people consume, even beyond South Africa.”

Apartheid is a system of racial segregation and marginalization that was implemented by South Africa’s National Party in 1948 and legally dismantled in 1994. Books, specifically those by South African authors and those with liberation messages, were banned and burned by the government during the apartheid era.

Book Circle Capital is one of 71 bookstores that Griffin Shea, a former international journalist from the U.S. now living and working in Johannesburg, is mapping in order to highlight Johannesburg’s thriving literary district.

Shea, owner of Bridge Books, which also features predominantly African and South African books, including children’s books written in South Africa’s indigenous languages, said he grew curious about the country’s publishing industry when looking to publish his young adult novel, “The Golden Rhino.” When he entered mainstream bookstores, Shea noticed only a few books by South African authors.

“Even in the general sections, the adult books and such, [there was] very little local representation, which is just such the opposite of what you would expect to get in an American bookstore,” Shea said. “You expect to see plenty of American authors, and plenty of other authors, too.”

Nkanyezi Tshabalala, an independent publisher focused on elevating South African works, said she has always been drawn to publishing stories “focused on South Africa, its history, its people or individuals who’ve done really remarkable things.”

Tshabalala said it’s important to read works by South African authors because they’re nuanced, culturally significant and come from a place of knowledge and understanding.

“Those parts of history, those parts of communities, those parts of cultures, survive the test of time and they’re carried on,” Tshabalala said. “It’s relatability. It’s preservation.”

Johannesburg has an extensive literary history that began shortly after the city’s founding in 1886. By 1890, Johannesburg had 11 documented bookstores. The first library opened the same year but functioned as a subscription library, meaning it was exclusive to white men who paid to join it.

This did not prevent Black readers from starting libraries of their own. The Bantu Men’s Social Centre founded a library for Black readers in 1924, which was the first known library for people of color in Johannesburg. By 1960, eight libraries had been built in Black townships. After pressure for integration grew, Johannesburg libraries were opened in 1974 to people of all racial classifications.

Shea is a walking encyclopedia of this history. In fact, he offers walking tours of central Johannesburg that highlight its literary history. The tour introduces participants to local booksellers, whose shops take various forms. Some have a row of books for sale in glass cases — books are in such demand that they are a high theft item — under shelves of bread or next to coats and handbags. Others have traditional storefronts, like Limbada and Company, founded in 1920 and now run by Imtiaz Limbada, grandson of the store’s founder.

Limbada said his books attempt to keep various cultures alive and present.

“Knowledge is power,” Limbada quipped as he leaned against the counter of his shop, lined with liberation literature and other books in a variety of languages.

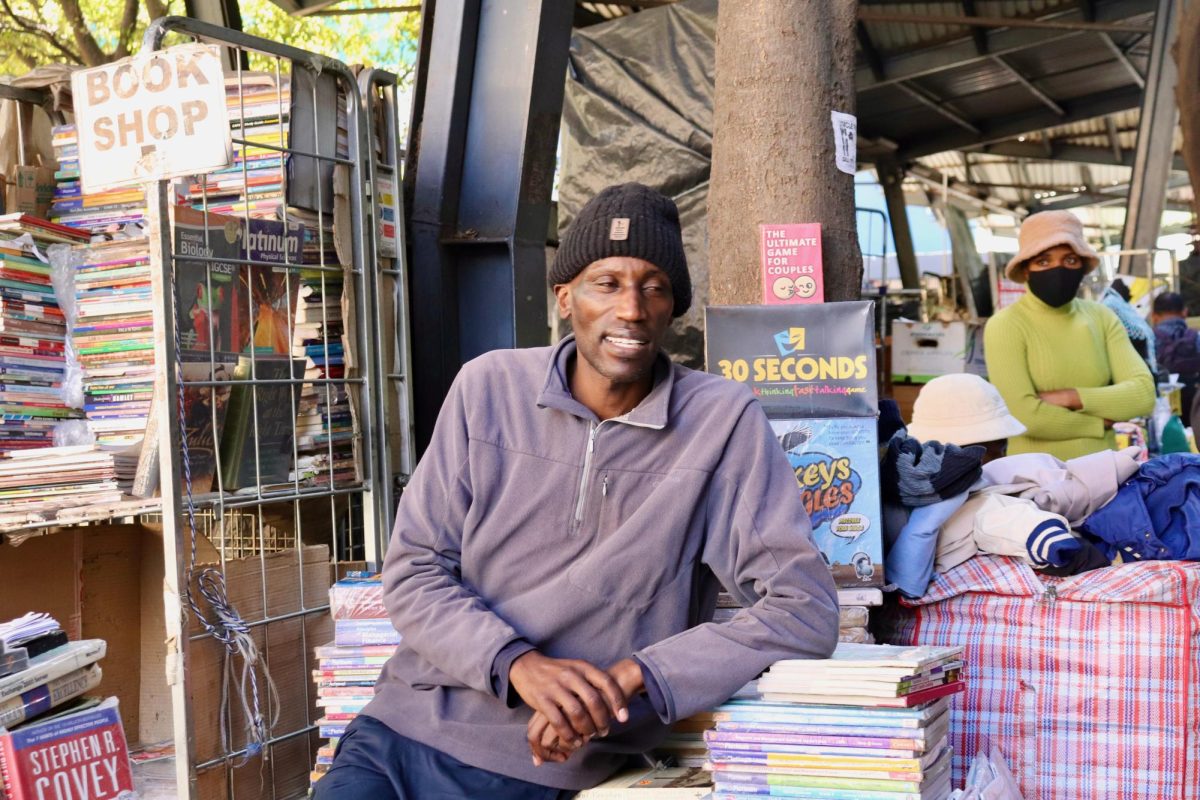

Other booksellers work from smaller outdoor stands, nestled between fruit vendors and technology booths in the center of Johannesburg. One owner, Henry Mugo, who sells books in a wide range of genres, said he loves being a bookseller because he gets to hear stories from customers and answer their questions about books.

Natasha France, Bridge Books’ store curator and publishing lead, said customers have told her that while they’ve been avid readers their whole lives, they’ve only picked up a South African book within the past few years. Now, South African books make up the majority of these readers’ collections.

“I think people think there isn’t much of a global audience for South African books,” France said. “[But] ‘Percy Jackson’ wasn’t read by the Greeks and ‘Harry Potter’ wasn’t read by witches and wizards. You don’t need to be from the same group of people to enjoy the stories.”

Bridge Books also runs the African Book Trust, a nonprofit focused on distributing African books to local schools and libraries. The African Book Trust is led by project program manager Thando Mavuso, who said South Africa’s education system isn’t doing enough to broaden the worldviews of children.

“That’s why it is important for us to distribute books; children’s books in local languages,” Mavuso said, “because they still get to experience the book. They still get to experience the story, but it’s in a language that they understand. And it helps them with the development of that language.”

Both Mavuso and Shea pointed out that books by South African authors are often more expensive than international books, even in the secondhand market. And access to books in general is a privilege, especially in schools where literary materials are limited.

“One of the biggest fights is ensuring that this goes into schools,” Langeni said. “Because of our economy and accessibility, [books are] not accessible to everyone. It’s a minority that has disposable income to spend.”

Langeni said it’s important to promote local stories because they offer representation, fight colonization and allow people to learn about the hard work of their predecessors.

“It’s that affirmation that our stories do matter, that good can come out of this continent,” Langeni said. “This ‘dark continent’ thing follows us around. Through literature, we can challenge that.”