The Frances M. Maguire Art Museum welcomed over 30 paintings, sculptures and other artistic works as part of the “Queens, Gods and Devotees” exhibition Sept. 26. The exhibition, featuring works from the Petrucci Family Foundation Collection of African American Art, was centered around the intersection of African American experiences and spirituality.

“Queens, Gods and Devotees” was curated by Susanna Gold, Ph.D., a Philadelphia-based curator and art advisor. Gold said the Maguire Museum stood out as a potential place to host the exhibit because it hosts other spirituality-based works.

“They have a lot of pieces that have to do with religion, with spirituality, and it seemed that it would be an interesting pairing to have this particular show complement some of the themes that they already have represented in the museum,” Gold said.

Some pieces, like Claes Gabriel’s “Queen of Time,” are more abstract, utilizing a wide variety of colors, designs and shapes. Others, like Tyler Ballon’s “This Too Shall Pass,” recontextualize biblical scenes with the members of the Black community.

Claudia Volpe, director of the Petrucci Family Foundation, said when picking pieces to feature, she considers quality and technicality, but also what voices are represented.

“We want to show the comprehensive story of African American art and the way that it’s evolved and practiced in the States,” Volpe said.

Volpe said the exhibition’s location in the Maguire Museum is especially relevant given the museum was previously the Barnes Foundation, which primarily featured modern European classical works.

“I think there is a little bit of confrontation of what this museum used to be and what the institution is looking to do in the future,” Volpe said. “So I’m glad we’re getting to pave that way.”

One particularly noteworthy aspect of the exhibition, Gold said, was that it features “so many Black artists in one place,” with the years of chosen works ranging from 1900 to 2023.

“This is a huge range in time over chronology,” Gold said. “To be able to see so many different artists of African descent that have been working in the American art history tradition for over a century, that’s really impressive.”

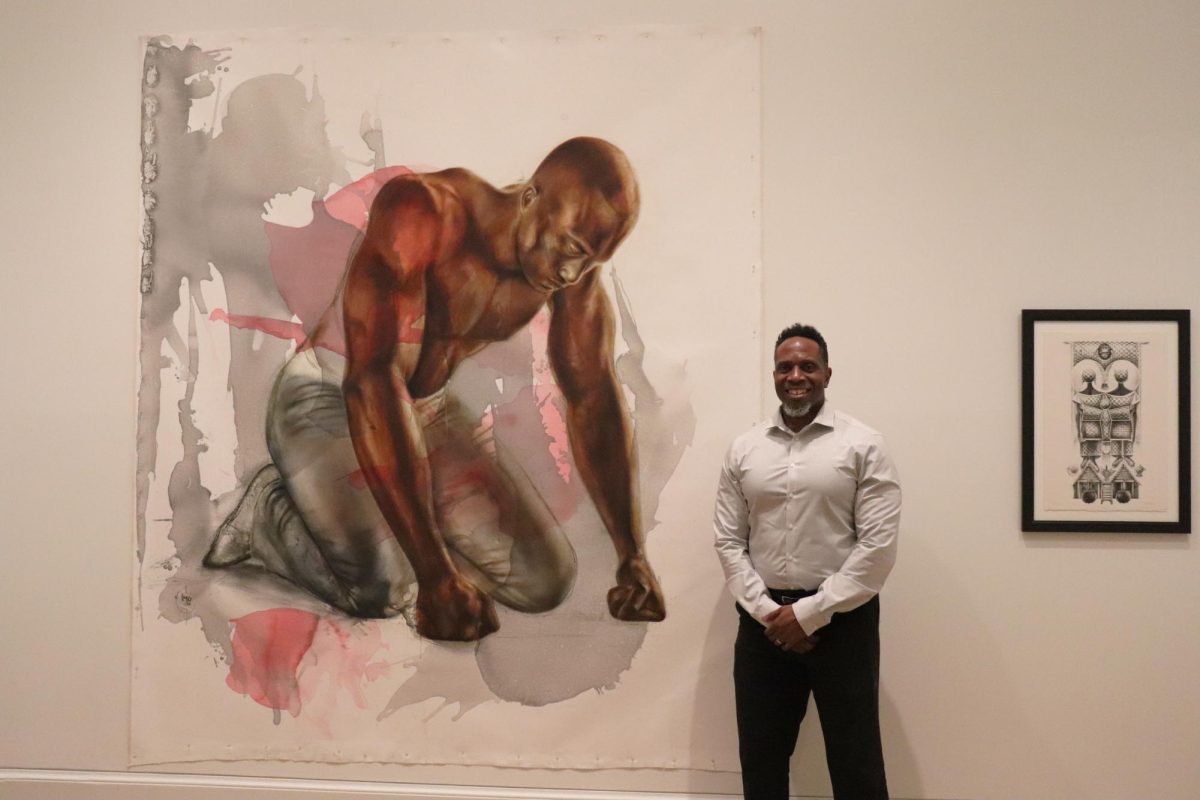

One of these artists is Imo Nse Imeh, Ph.D., whose painting “Feeding the Veins of the Earth (Grounded Angel),” is part of “Queens, Gods and Devotees.” Imeh, who is of Nigerian descent, said his identity, along with current events, inspires much of his artwork.

“I have been unable to separate what I do as an artist from the things that I see in the world around me,” Imeh said.

“Feeding the Veins of the Earth (Grounded Angel)” was created in 2020 during the covid-19 pandemic as commentary on the police brutality Black men face. The large-scale painting, utilizing red, brown and gray colors, depicts a Black man, who is an angel, kneeling and suspended in an “amorphous space,” as described by Imeh.

“I started creating them out of a kind of despair,” Imeh said. “The despair was fueled by what I was seeing, not just with the death of people because of the virus, but the hypervisibility of what Black communities were going through, especially with violence against Blacks and social injustice. I decided to construct a series of angels that would behave as witnesses for what Black people were experiencing here on Earth.”

Imeh said bearing witness in the face of injustice is a significant theme of his painting, which is part of a series of works he considers prayers. The idea of bearing witness was made especially clear to Imeh during the pandemic, as the lockdown accentuated the visibility of racial violence.

“The pandemic, for me, demonstrated that the world really can watch,” Imeh said. “They can watch some of the worst things happening to a community, because there was nothing else to do but watch. We were all on lockdown. We were all glued to our phones, and we all watched a man suffocate to death in nine minutes, an agonizing death.

“We also watched the world stand up and say, ‘This is wrong.’ And so, this piece really summons the idea of these angels as witnesses, but [also] this kind of collective body of witnesses to what it is we’re seeing. And then [it] begs the question, ‘What can we do?’”

Imeh’s work, which functions as a historical record, reminds viewers to take action and use their voices to incite change.

“In the image, there is this divine figure that is behaving as a witness for a group of people who I deem to be voiceless in a lot of ways,” Imeh said. “The call here is for us to recognize those who are voiceless, especially if we are able to offer voice and strength on their behalf.”