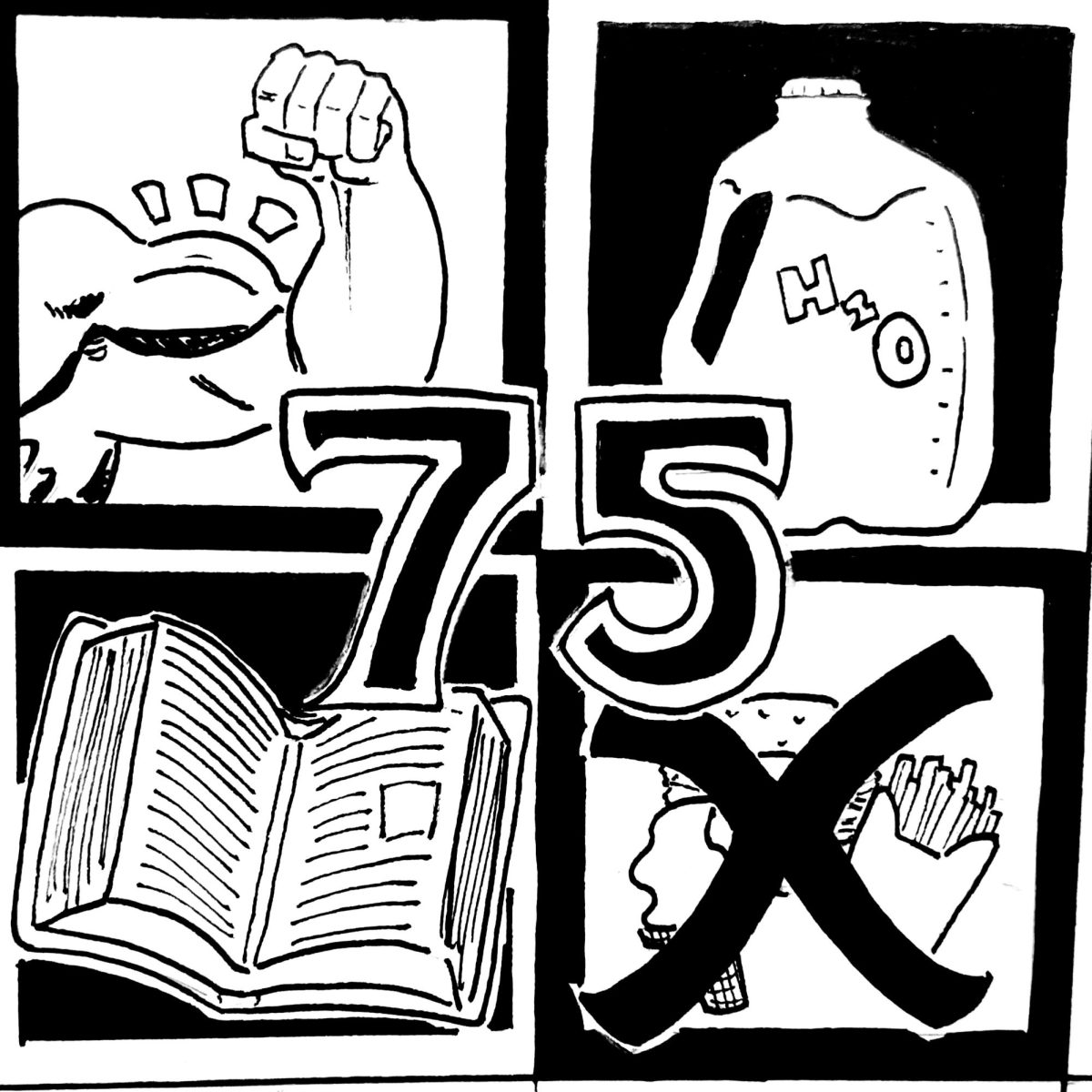

Reusable water bottles were supposed to solve a problem, not create a new one.

Once a symbol of sustainability, they’ve now become an accessory that consumers are quick to replace. As new styles and brands trend on social media, the push to own the latest model may be undermining their original eco-friendly purpose.

Around 60 million plastic water bottles are added to U.S. landfills and incinerators each day, according to the Container Recycling Institute, a non-profit organization dedicated to limiting packaging waste. Although reusable water bottles emerged as a solution to combat this massive waste, they’re now caught in their own cycle of disposability.

Clint Springer, Ph.D., associate professor of biology, director of the Institute for Environmental Stewardship and director of the Barnes Arboretum, said obsolescence — the idea that a product should be tossed when it becomes outdated — is engineered to encourage constant consumption.

“Marketers use this idea of obsolescence to their advantage in a very intentional way,” Springer said. “We’re bombarded with advertisements that are doing this all the time. ‘What’s the next best thing?’”

Led by brands like S’well, Hydro Flask, YETI, Stanley and, most recently, Owala, the U.S. reusable water bottle market is anticipated to expand at a compound annual growth rate of over 4% from 2023 to 2032, according to Allied Market Research. This growth is driven, in part, by increased awareness of sustainability, but also by the powerful influence of marketing that encourages consumers to upgrade unnecessarily.

Clare Joyce ’25, an environmental science major with a three-year-old Nalgene bottle, said most consumers overlook the full lifecycle of a reusable water bottle.

“I think it’s clear that we’re not thinking about everything that goes into a reusable water bottle when you can toss one to the side so easily,” Joyce said. “There’s so much energy and so many materials being used for a product to not be used to its full potential.”

Joyce’s observation points to a larger issue in sustainability: the disregard for the intended longevity of reusable products. Potential durability is rarely realized when bottles are replaced for reasons as superficial as new designs or trendy features, Springer said.

“Buying a stainless steel water bottle should last you, theoretically, for life,” Springer said.

To break free from the cycle of trend-driven consumption, consumers can focus on making thoughtful purchases that prioritize long-term value, said Alexandria Marro ’25, president of SJU Green Fund.

Marro chose their spout-lid Takeya bottle because it’s made of stainless steel, easy to clean and comes with a rubber bottom. They emphasized the importance of buying items that suit individual needs instead of mindlessly following trends.

“It’s very easy to have a habit of copying others’ personal tastes, and if you keep doing that, you’re going to keep going through the same cycle,” Marro said.