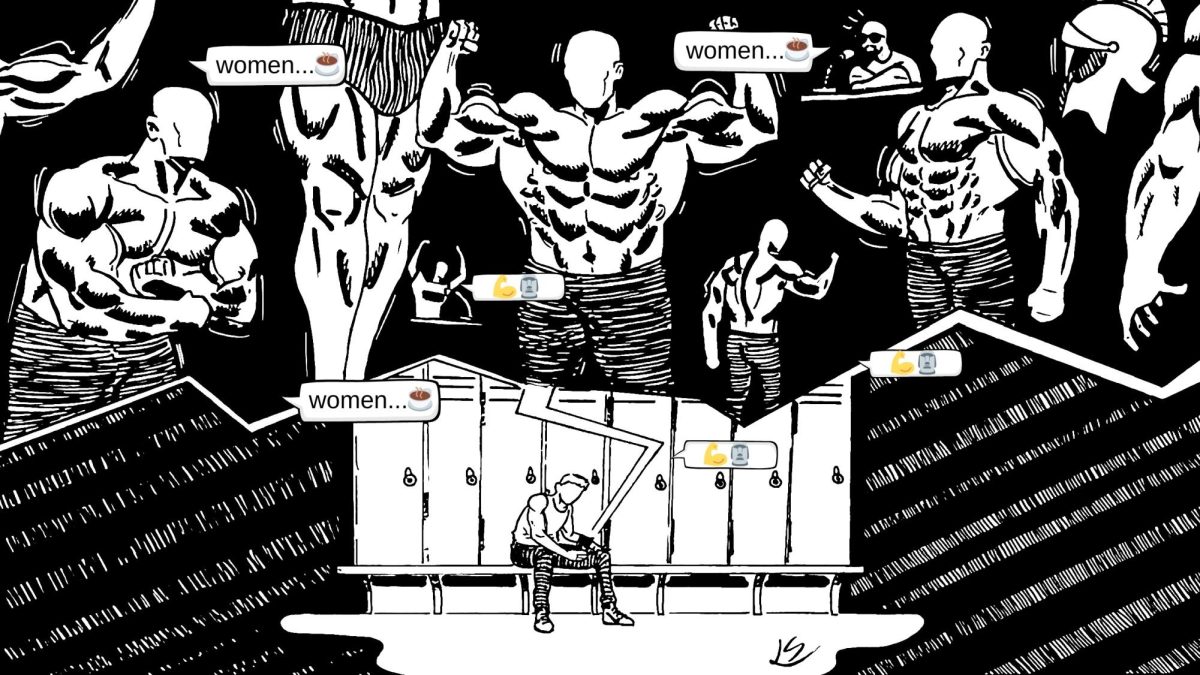

In the dark corners of the internet, the “gymcel” movement is having its heyday.

Gymcels are an offshoot of the incel (“involuntary celibate”) movement, an extreme misogynist subculture in which men blame women for their own lack of sexual intimacy.

Gymcels, who emphasize cultivating a bulky, muscular body, offer a glimpse into the larger “manosphere,” a primarily online misogynistic community known for its controversial figureheads like Andrew Tate, Joe Rogan and Jordan Peterson. Online gymcels flex their hard-won physiques to show them off, veins popping from their skin.

But gymcel content isn’t purely about fitness. It’s also about enduring tough times, providing for family or finding a woman who dresses only for God.

The manosphere

Annie Dabb, a U.K.-based freelance writer who writes about gymcels, said many men embrace the gymcel movement’s traditional form of masculinity as a way to counter what they see as an overly negative focus on “toxic” masculinity.

“There is this rhetoric, this discourse, of lots of men saying, ‘I’m part of this manosphere because women are so empowered, and women are all of these things, but there’s nothing to celebrate about masculinity. It’s just seen as toxic, and we’re talked down,’” Dabb said.

The reality, Dabbs said, is that “men have been reaping the rewards of this patriarchal society for so long.”

John Giovinco ’25, who goes to the gym every other day, said gymcel content creates an image of masculinity centered on muscle size and a “loner mentality.”

While Giovinco doesn’t agree with the gymcels’ views, he thinks many men feel cheated in society, which makes gymcel content and its problematic messages more appealing.

“They hear a lot of things like, ‘Oh, women want this, women want that,’ or things around those lines,” Giovinvo said. “And they start thinking like, ‘Oh, I’m not good enough.’”

Marble, muscles and masculinity

Richard Gioioso, Ph.D., associate professor of political science and an avid exerciser for 20 years, said male-centric gym content on Instagram celebrates hypermuscular physiques in a way that borders on “voyeurism.”

While Gioioso said he has noticed an increase in this kind of celebration of hypermuscular, “chiseled” male bodies in the past five to 10 years, it’s not necessarily a new phenomenon. Gioioso cited the statue of David by Italian renaissance artist Michelangelo as one example of the celebration of male muscles in history.

“Ancient Greece, ancient Rome, there was so much of a cult, or an admiration of masculinity. And I think that it continues,” Gioioso said.

Dabb said the hypermuscular ideal presented to men online is damaging, as it gives men an ideal they must aspire to rather than the opportunity to explore masculinity for themselves.

“There is a category presented to you online, and you are told that you can fit into it,” Dabb said. “And you are told that if you have this much protein and go to the gym and buy this subscription, sign up to this diet plan, then you can also be that.”

Harry Kearns ’25, another avid gym-goer, said while there is positive gym content online geared toward men, there is also a large section of content oriented toward men meant to sell them a product or a lifestyle, often marketed as a solution to their problems.

“It’s this very toxic mindset that a lot of these people have, where a lot of people don’t necessarily want you to be better,” Kearns said. “They just want you to keep buying whatever they’re selling, whether it’s a supplement or a program.”

Loneliness and the alt-right pipeline

Manosphere icons like Tate or Peterson are well known for their misogyny and conservative views on gender expression, but that has not hindered their popularity with young men. These views, perhaps by association, have trickled into gymcel content.

Giovinco acknowledged gymcel content is a step along the alt-right pipeline, the process by which people (particularly young men) are radicalized to believe in extremely conservative and potentially dangerous views.

“People fall into that [trap], and they start hearing, ‘Oh, it’s these people’s fault.’ And then they start to see, ‘Oh, you gotta beef yourself up if you want to get girls,’” Giovinco said.

Dabb said male-oriented gym content also holds appeal for men because it reinforces traditional gender roles where men serve as protectors. By bonding over gymcel ideas online, men protect the patriarchal privileges afforded to them in the gym.

“It’s almost reverting back to this idea that you need, in a very heteronormative sense, to win a woman, right? You need to present yourself as the ‘dominant, strong leader of the pack’ mentality,” Dabb said. “You are able to mate with the most women, you’re able to protect your space in that way.”

Kearns said online creators may not mean to perpetuate problematic rhetoric, but people who are “on the fence” may interpret their content in a problematic way. Kearns said this leads to an echo chamber.

“It becomes a tribal mindset of ‘us versus them,’ and that is just a problem with having stuff like that,” Kearns said. “Especially when you don’t have other relationships outside of it.”

Kearns said he thinks part of the reason gymcel content is so effective with young men is not only because of their youth but because the covid-19 pandemic took away formative years young people need for social development.

“When you’re younger, you’re a lot easier to be manipulated because you don’t have the wisdom and experience,” Kearns said. “Because of the lack of experience that you get from covid, you’re more likely to get invested into these hive minds, these red pill communities.”

Dabb said when men are lonely or in poor mental health, they’re more likely to believe in anything that might provide relief. But Dabb said gymcel content or masculine ideals are just as destructive.

“When you’re in the depths of poor mental health, or when you’re in the depths of loneliness, you’re going to grip onto whatever it feels like is going to get you out,” Dabb said. “So, you’re not going to necessarily realize that actually part of the problem may be part of the reason why you feel lonely and part of why you don’t feel good, because they are still holding this version of masculinity.”

Giovinco said one way he discerns potentially positive gym content from potentially gymcel content is whether it prioritizes overall physical and mental health over pure aesthetics.

“It’s being seen more as ‘You’re not working on yourself, you’re working so that others can see you,’” Giovinco said. “And I think that’s the kind of mindset that a lot of people have.”

Dabb stressed working out isn’t the problem for young men, but rather holding each other to inflexible standards for masculinity.

“If you work on yourself, that is great, but it shouldn’t feel like that you need to in order to be a man, right?” Dabb said. “There is no correct way to live your gender identity.”