At the Museum for Art in Wood in the Old City neighborhood of Philadelphia, people enter through glass, and the art enters through wood.

The wooden doors to the left of the glass entrance are made of reclaimed barn wood and stand more than 11 feet tall. The purpose of these wooden doors is to allow easy transport of large art structures into the museum for exhibitions or galleries. They are what first drew me to the museum, which I passed frequently while window shopping in Old City.

Katie Sorenson, director of outreach and communications for the Museum for Art in Wood, started volunteering 10 years ago and now coordinates exhibitions and programs. Sorenson took me to a staircase in the back room, leading up to nearly 1,100 objects on display.

“We do house a few historical pieces,” Sorenson said. “The majority of the collection is wood-turned objects because that’s how we began.”

Co-founded by brothers Alan LeCoff and Albert LeCoff in 1986, the museum began as the Wood Turning Center, offering symposiums and workshops. It was later called the Center for Art in Wood before being renamed the Museum for Art in Wood in 2022.

Amrut Mishra, assistant curator of the museum, said despite its many names, the museum’s goal has always been to serve as an accessible space and resource for education about wood in art. Admission to the museum is free.

“We believe everyone should be able to experience the artistic expression that we showcase at the museum, and free admission enables [us] to reach a wide range of audiences that might not have entered our space otherwise,” Mishra said.

The museum offers programs for artists, including the Windgate Arts Residency Program in Wood that takes place from early June to early August. Under the program, artists of all levels have the opportunity to live and work together to produce a group exhibition.

The people’s entrance to the museum immediately drops guests into a gift shop, with wooden earrings, cutting boards of various shapes and sizes, patterned rolling pins with blends of black walnut and white oak wood, sculptures and small furniture for sale.

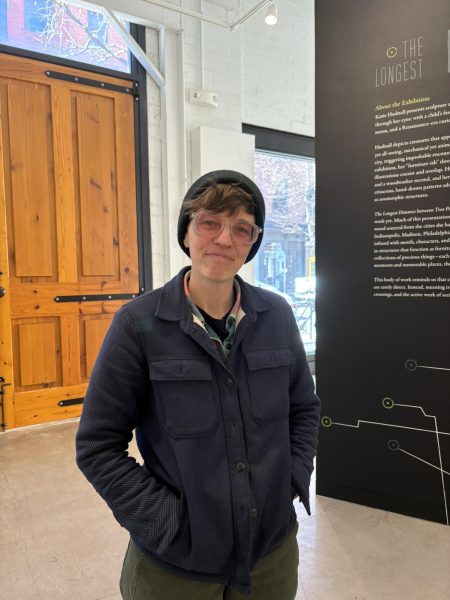

After making my way around the gift shop, I entered the exhibition space. The stairs to the gallery were to the left of the room. Coincidentally, I visited when artist Katie Hudnall, MFA, was setting up her exhibition. Hudnall runs the woodworking and furniture program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“When people hear woodworking, they think carpentry,” Hudnall said. “Even if they think furniture, they don’t necessarily think that’s an art form.”

I’m guilty of that. But that’s why I was there — to learn about wood in art and discover the motive for using this specific material.

After working in an industrial wood shop and developing wood carving skills later on, Hudnall said she likes using wood because it is ubiquitous.

“You find it everywhere,” Hudnall said. “Everybody has a connection to wooden objects, whether it’s a pencil or a wooden spoon or the floors in your house or furniture. Wood is a material that when people come to it, I think they associate it with something warm, they associate it with home, they have a relationship with it already.”

Everything Hudnall acquired to create her exhibition, “Longest Distance Between Two Points,” was either picked up from her daily four to five mile walks on the side of the street or found in a dumpster.

In one of Hudnall’s pieces, “A Cabinet for Lost and Found Things,” Hudnall shares the treasures she has found in different cities, ranging from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, to Philadelphia. In Hudnall’s handcrafted wooden drawers are sunglasses, washers, leaves and pedicure toe separators. These treasures connect Hudnall to the city and the people moving within it.

Hudnall said wood is attracting more young artists these days.

kitchen objects. PHOTOS: MONICA SOWINSKI ’26/THE HAWK

“I know a lot of young people who are trying to learn how to do woodwork, whereas when I was coming along, woodworking was seen as something your grandpa did,” Hudnall said.

Steve Rossi, assistant professor of art, teaches Sculpture and the Environment, a class that ties environmental art and socially engaged public art with woodworking.

“I find that the students’ mastery of techniques happens extremely quickly,” Rossi said. “In just a couple class sessions, students are confidently using wood cutting and joinery techniques that they previously had been entirely unfamiliar with to build complex sculptural forms.”

Sorenson said the museum pushes the boundary of what wood can do.

“There’s some really fine craftsmanship and beautiful artwork that can be created,” Soreson said.

My trip to the museum helped me understand that.