Meek Mill’s case sheds light on racial inequality.

Who is Meek Mill?

Meek Mill, born Robert Rihmeek Williams, is a Philadelphia rapper who rose to stardom after the release of his debut album “Dreams and Nightmares” in 2012. In the years prior to the release of his debut album, Mill resorted to selling drugs in North Philadelphia in order to make extra money, while simultaneously becoming a prolific figure in the underground hip-hop scene in Philadelphia. Before releasing “Dreams and Nightmares” Mill released a number of critically acclaimed mixtapes, including the influential “Dreamchaser” mixtapes. Mill has gone on to release another two full length albums, and has been a consistent presence on the billboard charts for nearly a decade.

Why is he in prison?

Mill has dealt with the legal system since 2008, when he was arrested on charges that included drug possession and illegal possession of a firearm. Mill was sentenced to 11-23 months in prison, although there were conflicting reports which claimed Mill was beaten by the police and sustained a concussion. Mill would spend the next decade under the critical eye of the criminal justice system, which included multiple stints in prison and 90 days of house arrest, mostly due to violating his parole by traveling out of the state of Pennsylvania without alerting his parole officer. In 2017, Mill allegedly assaulted an employee in a St. Louis airport. The charges were later dropped when a video of the altercation surfaced on social media. Later that year an instagram video showed Mill performing wheelies on a dirt bike in Manhattan while on a music video set, resulting in a charge of reckless endangerment, which was later dropped. Mill was sentenced by Philadelphia judge Genece E. Brinkley on Nov. 7, 2017 to a 2-4 year prison sentence for violating probation. The sentence was contrary to the recommendation of the assistant district attorney and Mill’s probation officer, who both agreed prison time was not necessary.

Who is the judge?

Genece E. Brinkley has been presiding over Mill’s legal proceedings for almost a decade. Brinkley has recently been criticized by the general public and celebrities such as Jay-Z and Kevin Hart, due to the possible correlation of her harsh sentence, and her relationship with Mill. Meek Mill’s attorney, Joe Tacopina, claimed the judge had a personal vendetta against Mill. Tacopina claimed Brinkley requested Mill to remix Boyz II Men’s “On Bended Knee” and give her a shout out on the song. Mill refused the request. Tacopina also claimed Brinkley wanted Mill to leave Jay-Z’s Roc Nation label, and sign instead with her friend Charlie Mack’s label. Again, Mill refused. The Meek Mill legal team has since filed a motion to have Brinkley removed from the case.

Why should we care?

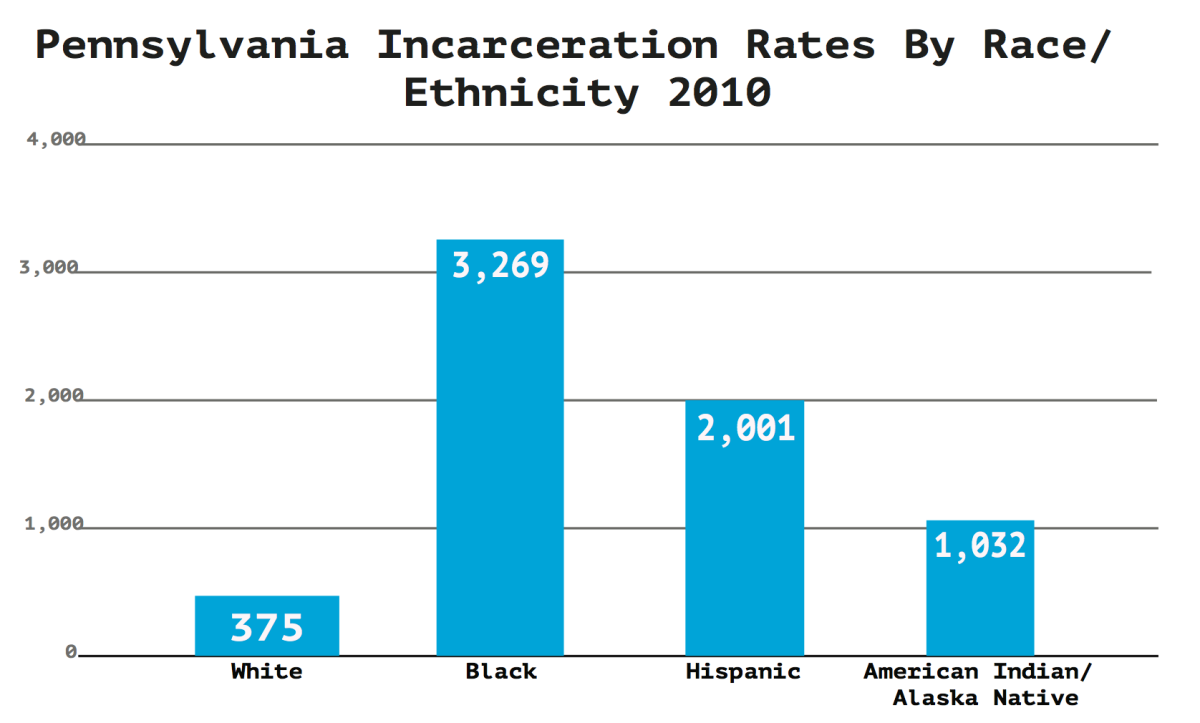

This particular high profile case reflects the differential treatment meted by the criminal justice system to African American men and white men in the United States. Between 2012-2016, the United States Sentencing Commission report found African American male offenders received sentences on average 19.1 percent longer than similarly situated white male offenders. Black men face unfair challenges and unequal treatment in the U.S. criminal justice system. Studies by Stanford’s Open Policing Project found African American drivers are pulled over and searched at a higher rate than white or Hispanic drivers. The study “found that police require less suspicion to search black and Hispanic drivers than whites. This double standard is evidence of discrimination.”

The vast expanse of discrimination, which Meek Mill represents, that shackles thousands of African American men every year, is summarized by Brooklyn rapper Jay-Z, born Shawn Carter, in a piece he recently wrote for the New York Times.

“For about a decade, he’s [Meek Mill] been stalked by a system that considers the slightest infraction a justification for locking him back inside,” Jay-Z wrote. “What’s happening to Meek Mill is just one example of how our criminal justice system entraps and harasses hundreds of thousands of black people every day. I saw this up close when I was growing up in Brooklyn during the 1970s and 1980s. Instead of a second chance, probation ends up being a land mine, with a random misstep bringing consequences greater than the crime.”