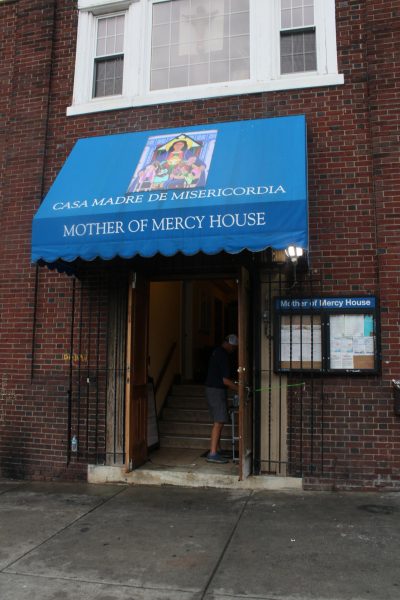

Located alongside rowhomes and businesses in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Mother of Mercy House may pass for an ordinary red brick building. But to community members battling life-threatening substance abuse disorder in the center of Philadelphia’s decades-long opioid crisis, the humble clinic is a critical lifeline and a beacon of hope.

Behind the doors of Mother of Mercy House, members of St. Joe’s Institute of Clinical Bioethics confront this public health crisis head on, administering free wound care to individuals who have acquired wounds from injecting xylazine and medetomidine. Both these substances, which are veterinary tranquilizers, are often combined with other opioids like fentanyl. Resulting wounds can run deep to the bone, requiring hospitalization or amputation, and, in severe cases, leading to death.

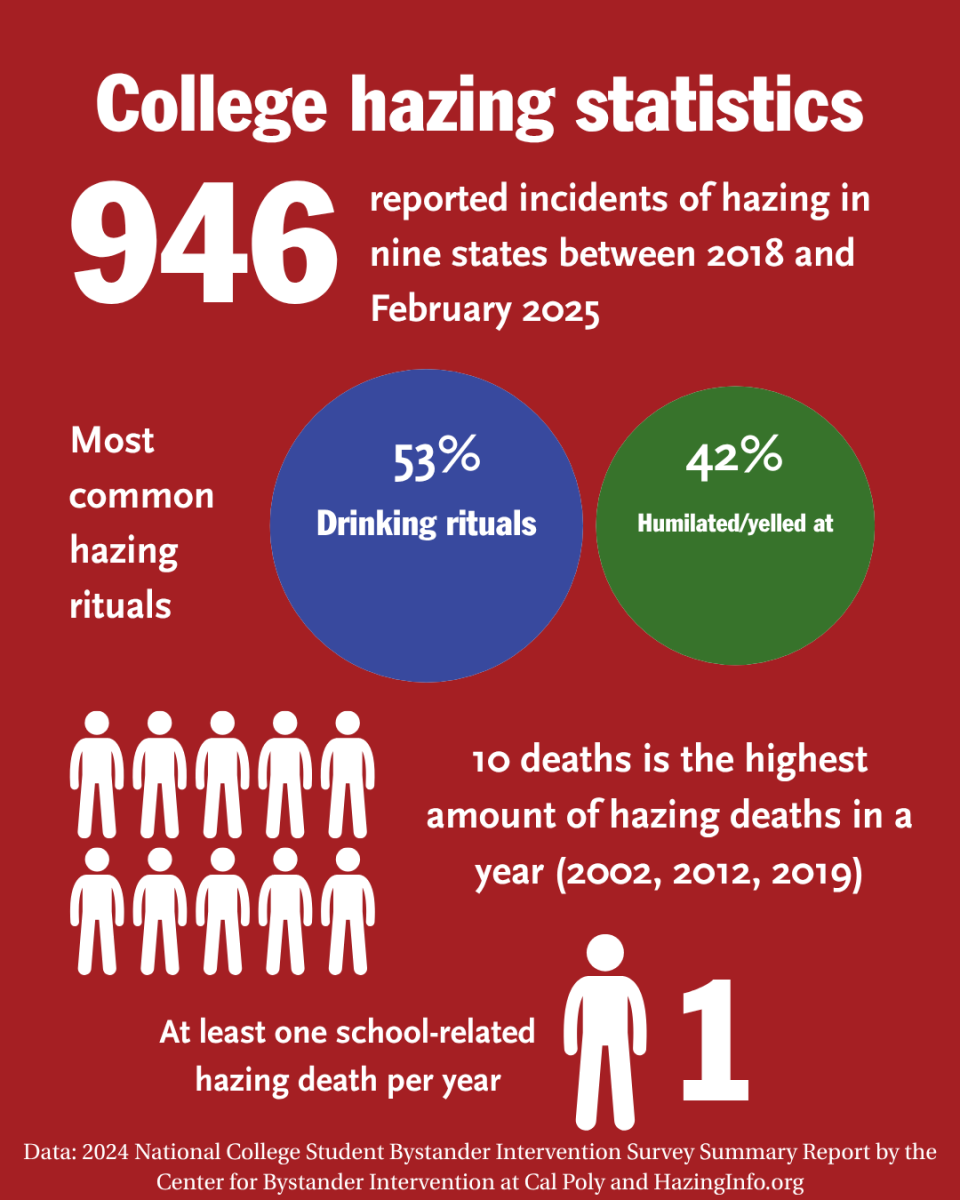

According to the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, there were 1,122 overdose deaths in 2023. This was a 7% decrease from 2022’s previous high. Available data for 2024 suggests a further decrease.

The Kensington neighborhood, nationally known for the frequent public sale and use of illegal drugs, faces a crucial need for wound care. Between January 2020 and March 2025, there were 5,471 emergency department visits for people with substance use-related skin and soft tissue injuries in Philadelphia.

Peter Clark ’75, S.J., Ph.D., professor of theology and director of the ICB, said the institute sought to provide care in Kensington after noticing it was “the epicenter of the opioid crisis.”

“This is one of the few things where our students not only talk the talk, but they’re walking the walk,” Clark said. “They’re putting the Jesuit values into action. They’re literally with the most vulnerable people in society.”

Fredy Abboud ’26, an ICB undergraduate fellow, said witnessing the epidemic in Kensington firsthand is important for developing an understanding of it.

“It is vital to be able to see for yourself how bad, how severe, the issue is, how severe the problem is, and to see the struggles that the people are enduring … when you have a better understanding, inevitably, you’ll be able to address it in a more efficient way down the line,” Abboud said.

week from its Allegheny Avenue location, Sept. 25.

The clinic’s beginnings

ICB members were first present at Mother of Mercy in early December 2023 according to Steven Silver, MBA ’25, assistant director of the ICB and opioid grant administrative coordinator.

Silver secured a $100,000 grant for the clinic to provide services, of which $13,000 was specifically designated to wound care. The grant covers supplies like bandages and saline sprays and funded the exam table for Mother of Mercy House’s wound care room.

Currently, 10 student EMTs work as fellows within the ICB at the wound care clinic. The fellows are assisted by other undergraduate students and also work with physicians. The wound care clinic is part of the ICB’s BIPOC Health Promoter program, which aims to provide healthcare to people of color throughout Philadelphia and its surrounding areas.

In 2023, white Philadelphian overdose fatalities decreased by 15%, but Black Philadelphian overdose deaths only decreased by 5% and Hispanic Philadelphian overdose deaths increased by 2%.

“From the developing world to the first world, there’s always going to be a minority, and you have to be an advocate for whoever you’re treating, whoever you’re experiencing life with,” said Ean Hudak ’26, an ICB undergraduate fellow.

Treatment and wound care

The clinic offers wound care services twice a week, on Tuesday and Thursday, for about two or three hours each day. The clinic functions similar to a doctor’s office, with patients waiting in the hallway outside the clinic room before receiving care. When it’s the patient’s turn to receive treatment, their wounds are cleaned and wrapped.

“You’re just kind of patching them up,” Dianne Hoffmann, executive director of Mother of Mercy House, said. “A lot of times, they send a wound care package with them because there’s other places down the street they can go tomorrow, but sometimes that feels like Mount Everest to them.”

Emma Anderson ’26, an ICB fellow, said they typically see between six to eight patients in a week, but the number of patients who receive care varies. Time spent on each patient can also vary depending on the severity of their wounds.

“It can take a long time if they’re bad wounds, especially if they’re bilateral, and a lot of them are, so that can take almost an hour,” Anderson said.

The wound care process has various steps, Anderson said. First, the EMT or nurse removes the old wound dressing. Depending on the severity, saline will be used to moisten the wound and the dressing will be physically cut off. Next, saline is used to rinse off exudate, the fluid produced by the body in response to damage, from the wound. This is followed by wound wash, Dakin’s solution — a topical antiseptic — and sometimes iodine. Depending on the wound, a cream or ointment will be applied.

The care process finishes with wrapping the wounds in non-adherent dressings, roller gauze and an elastic bandage.

Strict protocols, Clark said, are enforced for student and practitioner safety.

“We have protocols on double gloving, masking, because many of these patients could have TB,” Clark said. “Many may [have] HIV, many may [have] Hep. C., so we’re very particular about how we do that.”

Wound care, however, is not limited to inside the clinic. Currently, the ICB uses a wagon “with two tackle boxes full of materials” to administer mobile wound care to individuals on Kensington’s streets.

A major requirement of the wound care clinic, Clark said, is “continuity of care.” To uphold this requirement, the clinic is partnered with groups like the wound care team at Temple University Hospital.

“We established a relationship with them,” Clark said. “So, if one of our patients is going to the ER at Temple, we call the wound care team in advance. They meet the patient in the ER, and they circumvent the ER at that point, so our patients get seen.”

Care for the whole person

The ICB’s mission expands beyond physical wound care. The clinic, Clark said, has a relationship with Project HOME, a Philadelphia nonprofit addressing poverty and homelessness. At a patients’ request for housing, a Project HOME van is called to pick them up. A similar call can be made for patients who wish to go into rehab.

“It’s just not a clinic that’s just dealing with wounds,” Clark said. “We’re trying to deal with the issue.”

Mother of Mercy House and the ICB fellows also do food and resource distribution in hopes of providing additional support.

Hoffmann said wound care is not just for physical healing, but also emotional healing.

PHOTOS: SAHR KARIMU ’26/THE HAWK

“You’re not going to cure everyone … They still need to be seen and loved and heard, and that’s it. At the end of the day, that’s the most important thing,” Hoffmann said.

Silver said confronting the stigma around Kensington is included in “cura personalis,” or care for the whole person.

“You learn these people, you learn their stories and you realize that they’re just humans at the end of day, they’re just people, just like us, but they just fell on tough circumstances,” Silver said. “If we can be there to provide some type of bridge to help, or provide a way out or just a helping hand, it opened my eyes to seeing like the full person, the full care of a person.”

Because death is an ever-present reality, confronting the epidemic can take an emotional toll. The gratitude shown by patients, Hudak said, keeps him pushing forward.

“Yes, it’s sad, and it takes a toll on you, but they’re beyond grateful for my help, and that’s what keeps me going,” Hudak said.

The personal connections forged between patients and caregivers, Clark said, is also central to him both as a professor and Jesuit.

“The nameless and the voiceless now have a name and a voice,” Clark said.

Rev. Brendan Lally, SJ • Oct 1, 2025 at 7:18 pm

This is a great article and a tribute to the extraordinary work of Fr. Peter Clark and the opportunities he provides to the students of St. Joseph’s University to engage in the Ignatian-Jesuit mission of bringing the love of Christ to some of those in greatest need!