Nuevo Progreso, Mexico — For more than two decades, 63-year-old Maria Luisa Lima Ortiz has been running Taqueria El No Que No, a tented taco stand in a line of taco stands along Calle Sonora in Nuevo Progreso, a small town in Mexico that borders southeast Texas.

Every day, Mexican and U.S. citizens cross back and forth across The Progreso-Nuevo Progreso International Bridge, by car and by foot.

Lima Ortiz’s livelihood depends on that bridge, on the ability of tourists to cross into Nuevo Progreso and pay $4 for an order of five of her signature beef and steak tacos.

On Oct. 31, new fencing was installed along the pedestrian walkway on the bridge, which spans the Rio Grande, in an apparent effort by the U.S. government to deter thousands of refugees making their way north through Mexico to the U.S. border.

As the group has wound its way north toward the U.S. President Donald Trump warned that U.S. soldiers will be stationed at the border to deal with the “invasion.” The U.S. announced on Oct. 29 it was sending 5,200 troops to the border with Mexico, and on Oct. 31, Trump said he would send as many as 15,000 troops. By Nov. 5 the group was about 600 miles from the U.S. border.

Lima Ortiz said she is worried that if the situation escalates, she will have to close her taco stand.

“On the one hand, we know they’re human beings,” Lima Ortiz said through a translator. “But what fault do I have? As a person who lives here in a border town, it’s going to be chaos, and that’s a concern.”

There are a lot of unknowns whirling in Nuevo Progreso: How many refugees will complete the journey? Where will they surrender at the border? How will U.S. troops respond?

Juan Gamon, a clerk at El Disco Super Center, shrugged at the thought of the refugees causing any trouble in Nuevo Progreso. In fact, he said he thinks they will surrender to U.S. Border Control officials at another, more prominent crossing that is better signed, like maybe one of the three border crossings in Matamoros, near Brownsville, Texas.

“If they come here, it’s no big deal,” Gamon said through a translator. “I’m not concerned. They’re just people.”

Esteban Zuñiga, 16, who works at the Taqueria El No Que No, is not afraid of the refugees, either, but he does wonder how the U.S. will respond to them.

“If it becomes true what Trump is saying, that the U.S. soldiers will strike back, it will hurt business,” Zuñiga said through a translator.

Zuñiga said he isn’t sure what other young Mexicans in Nuevo Progreso think. He stopped going to school six months ago and now works long hours at the Taqueria, so he has no friends to talk to about the situation.

“I can’t do anything about it,” Zuñiga said. “Who should be concerned is the people in charge of not letting them through.”

On Avenue Buenito Juárez, the main drag in Nuevo Progreso, which is lined with pharmacies and dentists and street vendors selling food and tourist wares, 46-year-old Felix and 39-year-old Graciela said they empathize with refugees. The couple, who sell leather goods, purses and wallets at a sidewalk stand, were originally farmers from Mexico City. They said they were forced by the government to flee their home 25 years ago after speaking out in defense of Mexico’s indigenous people. They asked that their last names not be used.

“We traveled here for the same reasons they [refugees] are fleeing,” Felix said through a translator.

The couple said the refugees from Central America haven’t done any harm. Even though they said the refugees might aggravate the situation along the border, they want to help in any way they can.

“No one leaves just for adventure,” Graciela said through a translator. “They leave because they have to.”

At the same time, Felix said he appreciates Trump’s nationalist motivations and wishes Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto would act similarly to protect Mexico’s interests.

“I understand the nationalist rhetoric,” Felix said. “We are looking for change in Mexico, not movement to the U.S.”

On the U.S. side of the border, Thomas De La Cruz is a lecturer in writing at The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley in Edinburg, Texas, which is about 65 miles from the U.S.-Mexico border. A Mexican American, De La Cruz travels to Nuevo Progreso at least three times a month, mostly for entertainment but also for dental work, medicine and contact lenses. He brings back medication for other people who can’t afford it or who can’t visit the doctor to get a prescription.

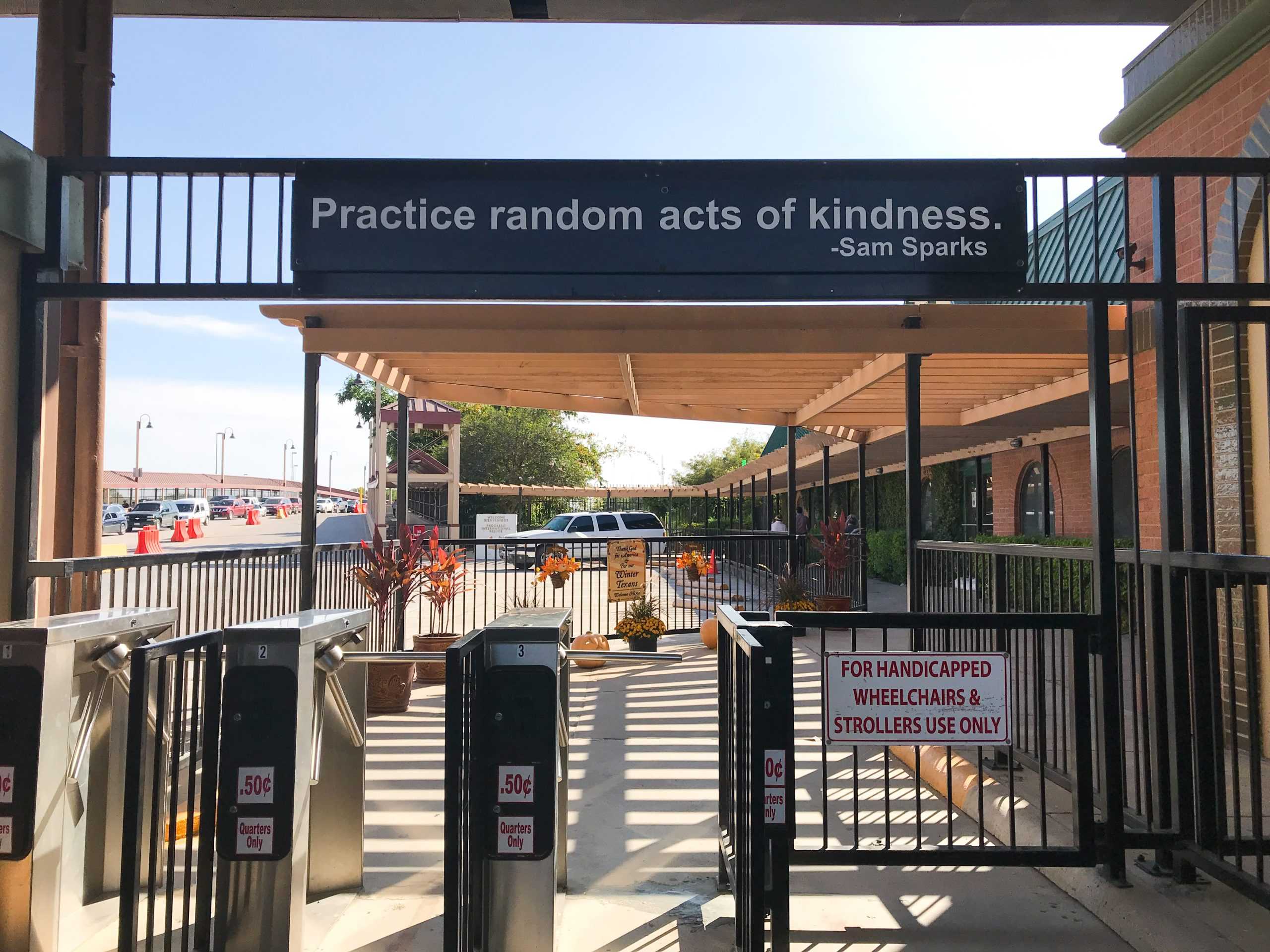

On a Nov. 2 visit to Nuevo Progreso, he noticed the new fencing erected by the U.S. Border Patrol. He said he has seen a growing reluctance among people he knows to cross into Mexico. He blames “scare tactics,” “fear mongering” and “rhetorical bullshit” for that reluctance.

“The elections are coming up,” De La Cruz said. “I think that matters a lot. I think fear is a great motivator. Fear pushes people to do things without thinking about why they’re doing them.”

De La Cruz said he isn’t worried about the refugees seeking entry into the U.S. He and his wife have discussed sheltering people who need it.

“You can choose to make your decision based on fear, or you can choose to make your decision based on kindness,” he said.

And while De La Cruz said Trump has amped up rhetoric surrounding immigration, the issue is nothing new for people like him who live in the Rio Grande Valley, a four-county region on the southern tip of Texas that is home to about 1.3 million people of which, according to U.S. Census estimates, is almost 90 percent Hispanic.

“This is the valley,” De La Cruz said. “As Gloria Anzaldúa says, where one country rubs against the other one, or one border or culture rubs against the other one, that rubbing creates a wound. It hemorrhages. The valley is that wound, that hemorrhaging. It scabs over and wounds again, scabs over and wounds again.”

Alyssa Cavazos, Ph.D., assistant professor of rhetoric and composition, also teaches at The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. Cavazos came to the United States from Mexico as a young child. She currently lives about 30 miles from the border, in the U.S.

Cavazos said she rejects the word “invasion” to describe the refugees attempting to seek asylum in the U.S.

“I don’t see it as that,” she said. “I see it as people trying to find a safe place.”

Cavazos added she is not afraid of the refugees. What frightens her is the troops Trump plans to send to the border.

“I fear for the life of people,” Cavazos said. “I see images of families, mothers with children. I have a little girl who is three years old, I see those children in her. That is the thing that scares me the most. I don’t want a tragedy. I don’t want death.”

Felix said fear seems to drive the way many Americans see and interact with the world.

“People from the U.S. are cold and enclosed to their environment,” he said. “They close themselves off. There’s fear in the world, and they close themselves off.”