Former activist discusses time at St. Joe’s

Dr. Rodney Powell ’57 stood between civil rights activists John Lewis and James Bevel, both of whom were seated at a whites-only Walgreens lunch counter in Nashville, Tennessee on March 25, 1960. Resistance to racial desegregation from local establishments had reached a peak in the city. A sign had been installed by Walgreens management: “Fountain closed in interest of public safety.”

All three men were there as part of non-violent protests against segregation. Powell was helping to monitor that day’s demonstration.

“Sometimes you sat at the counter, sometimes you were part of a group that observed,” Powell said. “Or you were part of a group that was sort of a monitor to make sure that those who were on those frontlines sitting were okay, weren’t having regrets or didn’t feel they could continue to be nonviolent.”

Two months after the Walgreens demonstration, Nashville would become one of the first major Southern cities to desegregate “whites only” lunch counters.

After graduating from St. Joe’s in 1957, Powell had enrolled as a medical student at Meharry Medical College in Nashville, one of the oldest and largest historically black medical schools. He remained committed to the civil rights movement, helping to organize the 1961 Freedom Rides, which challenged laws enforcing segregation on public transit.

Nearly 60 years later, Powell said his involvement in civil rights efforts was never a conscious choice.

“It was something that happened because the injustices were so glaring,” Powell said. “Wanting to rectify these social issues was something that I don’t recall making conscious decisions to be part of, but just gravitated toward.”

As a St. Joe’s undergraduate, Powell had other ideas for his life.

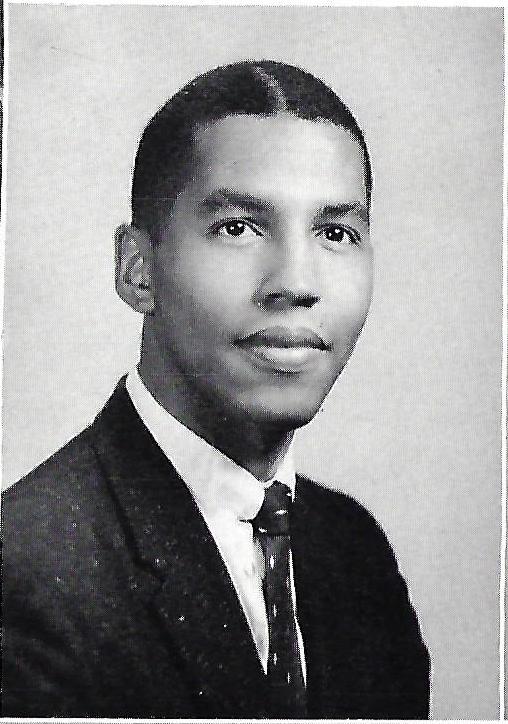

Powell came to St. Joe’s with the goal of attending medical school. He worked part-time all four years to save for his medical education while commuting from his North Philadelphia home. Powell was one of the only black students in his class year, and he said he did not feel welcomed by his peers.

“I was there,” Powell said, “but I wasn’t invited into any of the social activities.”

Powell also said issues of race were not discussed in his classes or elsewhere on campus. Major events impacting black Americans—in particular, the murder of Emmett Till and the Montgomery bus boycotts—were never talked about, at least not in front of him.

“Never once in that whole four-year period did any member of the faculty or any of my fellow students ever seek to address or understand the significant issues that were happening,” Powell said.

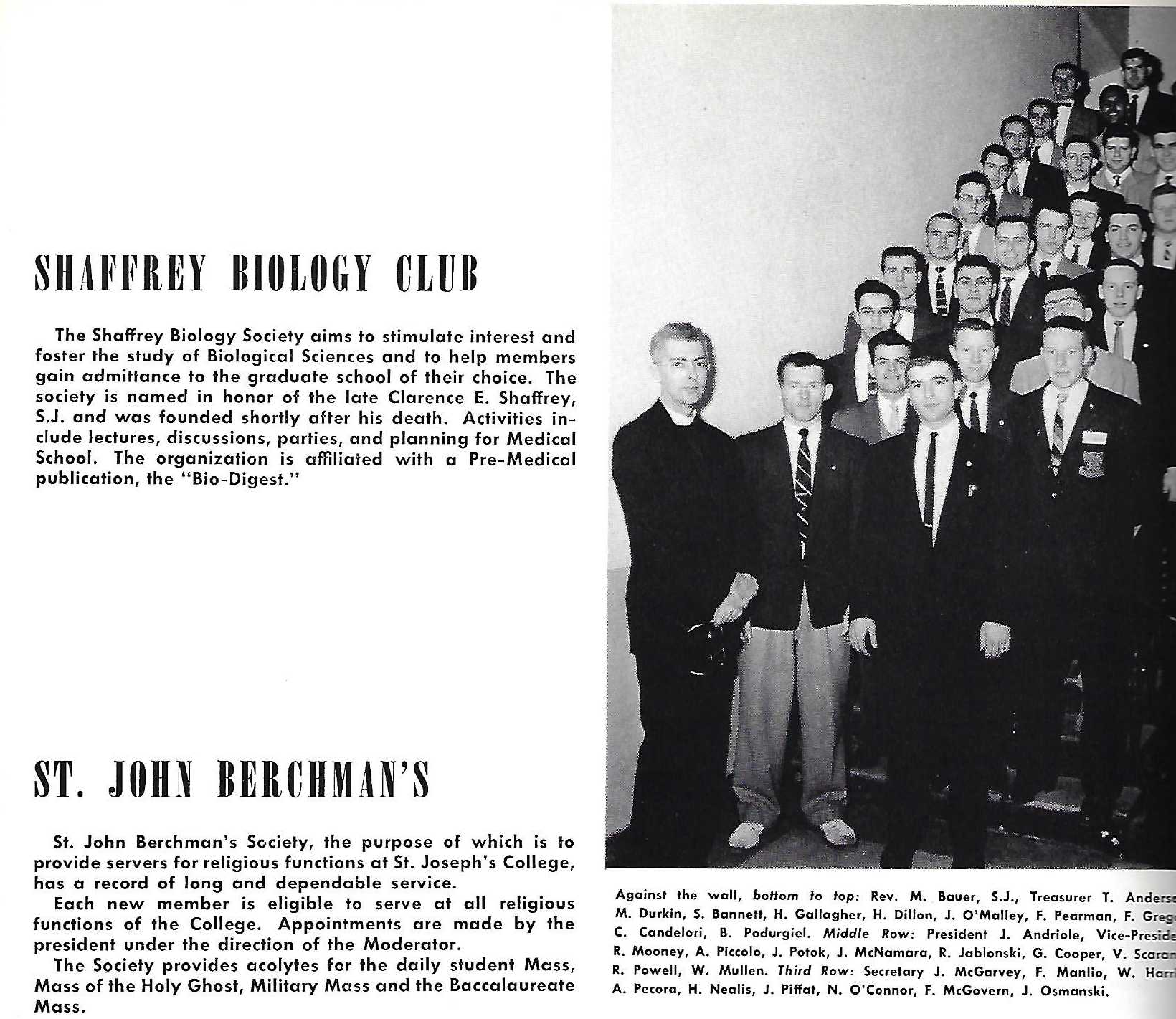

Powell dedicated much of his time at St. Joe’s to academics. He was a biology major in the pre-medical track, a program completed by about one-third of the students who originally enrolled. His rigorous program of study left little time for extracurricular involvement. A major campus event Powell did become involved with is one he still remembers “keenly and painfully.”

In 1955, during his junior year, Powell was approached by several classmates he had never spoken to before. The students were performing in a one-act play competition sponsored by the Cap and Bells Dramatic Society, what was then the university’s theater company. They told Powell that, because of Powell’s race, he was most qualified to perform the song “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” a spiritual song originally published in the 1867 compilation “Slave Songs of the United States.”

In an Oct. 13, 1955 article in The Hawk about the contest, Powell is listed as one of six juniors performing in the play “Who Stand and Wait.”

“Basically, they were asking me to subject myself to all of the indignities and the suffering of my ancestors who were slaves,” Powell said, “and I guess in my desperation not to make waves, to fit in, I agreed.”

A bright spot during Powell’s four years at St. Joe’s came in the form of his friendship with Sherman Bannett ’57, now a retired radiologist living in New Jersey. Bannett was a peer in the pre-medical program whom Powell met his first year. The men still speak regularly, maintaining a 66-year-long friendship.

Just as Powell was part of a small population of black students at St. Joe’s, Bannett was one of the only Jewish students. As a result, Bannett said, he and Powell were mostly left alone.

“We were such a minority that nobody paid much attention to us,” Bannett said.

Like Powell, Bannett was also intensely focused on his academic work and commuted to campus from home. In general, St. Joe’s students at that time did not depend on school friends for socializing, Bannett said. His friendship with Powell was an exception.

“He’s certainly the closest [friend] I ever had in college,” Bannett said. “We enjoyed each other, we spent much of our studying [time] together. We had lunch together every day, and we had our classes together.”

After leaving St. Joe’s and becoming involved with the civil rights movement in Nashville, Powell would go on to realize his goals of becoming a doctor and began a career in public health. He married Gloria Johnson, a fellow student at Meharry who had also been involved in the movement. The couple had three children: April Powell-Willingham, Allison Powell and Daniel Powell.

In 1975, Powell and Johnson separated. Five years earlier, Powell had disclosed to Johnson a long-held secret: he was gay.

“It was hard to accept that I was the person that was the object of derision when people used terms like ‘queer’ and ‘faggot’ and ‘sissy,’ and I didn’t want to be that person,” Powell said. “Did I know I was gay [when I was younger]? Not really, but I knew I was very different. I never quite put a name on it until much later in life.”

Two years after Powell and Johnson separated, Powell moved to Hawaii alone. He had found a job there in the medical field. Powell would later find, too, that Hawaii offered him a future as an openly gay man. Shortly after the move, Powell met his now husband Bob Eddinger, Ph.D., a zoologist. Powell-Willingham, Powell’s daughter, said Eddinger eventually became part of their family.

“I like to think that we were on the vanguard of blended families in terms of a gay parent, or gay parents, because we consider Bob, my dad’s partner, to be one of our parents,” Powell-Willingham said. “He considers us to be his kids, too.”

As the LGBTQ rights movement gained traction in the late 1990s, Powell was once again at the crossroads at which he’d found himself in Nashville: stay silent or get involved. He chose the latter.

Powell-Willingham described her father as having a natural determination about him.

“While he’s extremely charming and well-spoken and gracious, he’s also stubborn as hell,” Powell-Willingham said. “When he turns that energy and focus to something that he wants to accomplish, he’s all in.”

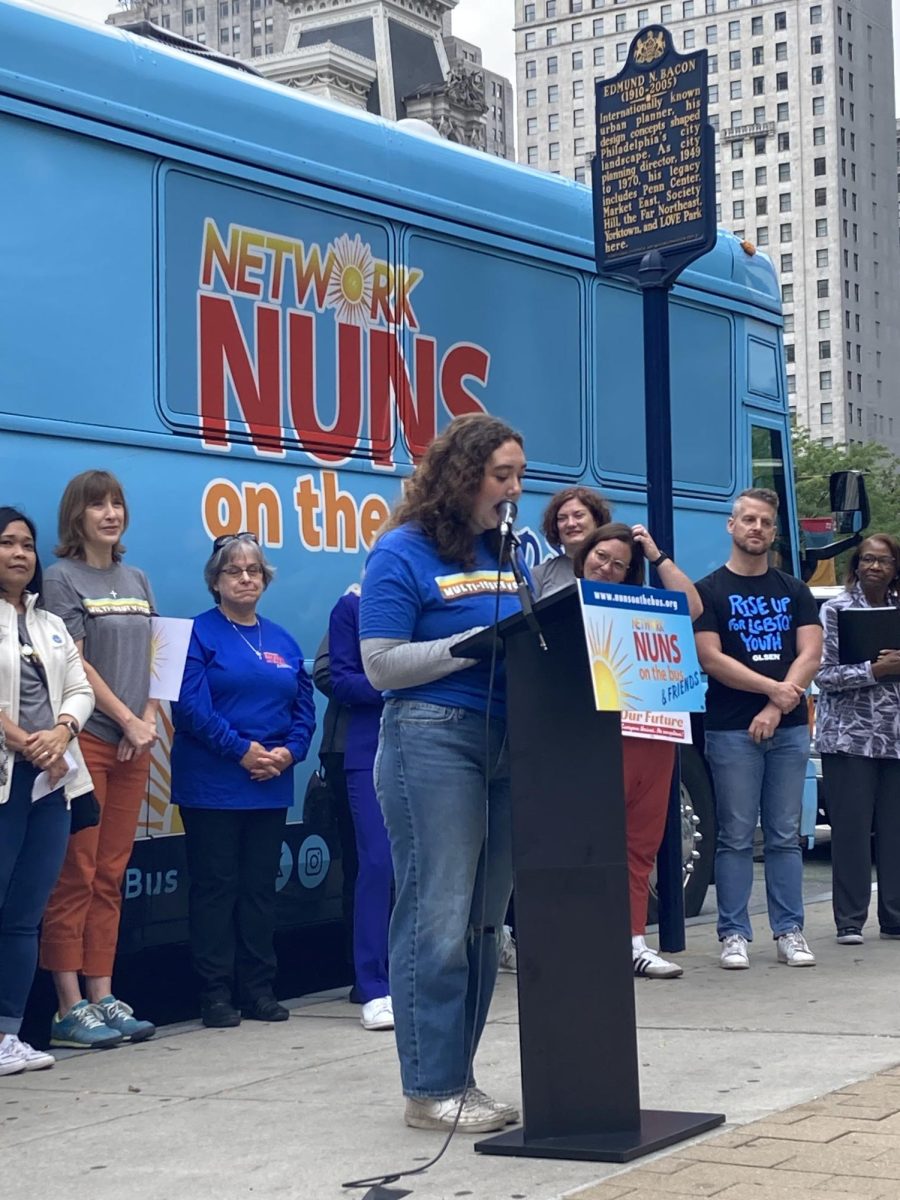

Through a mutual friend, Powell became involved with the LGBTQ activist organization Soulforce, which was founded in the civil rights movement’s tradition of nonviolence. In 2005, he helped to plan the group’s Equality Ride.

Drawing inspiration from the 1961 Freedom Rides for a new civil rights movement, the Equality Ride stopped at religiously-affiliated universities across the country in hopes of reaching religious leaders who used the Bible to justify anti-LGBTQ rhetoric.

“[Soulforce] really moved the needle,” Powell said. “It helped to highlight the injustices of homophobia and the church’s role in it.”

The man who once feared “making waves” as an undergraduate at St. Joe’s went on to campaign for civil rights across two generations and for two minoritized groups. As for the progress yet to come, Powell said he views the socially aware mentalities of younger generations as the country’s “saving grace.”

“There are people who have gone before you, as there were before me, and we all build on the lessons learned from each generation,” Powell said. “I’m a real optimist about where it’s going to lead us.”