Carter Geer ’25 was in Francis A. Drexel Library on March 30 when Philadelphia and Lower Merion police officers arrived, weapons drawn, and told everyone to put their hands up.

Within minutes, Geer and other students were escorted out of the library, unsure of what threat they were under.

“I was really just in shock afterwards,” Geer said. “I was outside the library, hoping I would see somebody that I knew, but I didn’t, so I sat there in shock. I couldn’t believe what was happening. I couldn’t figure out how to go on with the rest of my day.”

At 3:09 p.m. while Geer waited outside the library, the campus community was informed through an alert on the SJU Safe system that there was no emergency on Hawk Hill. A phone call regarding a potential active shooter in the library, which the Office of Public Safety & Security had received about 30 minutes earlier, had proven to be a false alarm.

The threat was gone, but the trauma lingered.

“Afterwards, you almost feel invalidated for everything you experienced because there was never an actual threat,” Geer said.

David Yusko, PsyD., a counseling psychologist in Bryn Mawr who specializes in treatment of PTSD and anxiety disorders, said perceived exposure to trauma affects the brain the same as actual exposure.

“Students felt and thought that they were potentially about to die,” Yusko said. “Now, that experience, by definition, is what we would call a capital T trauma or criteria, an event trauma that qualifies the diagnosis for post-traumatic stress disorder, trauma, and it opens up the pathway to develop PTSD from there.”

What students like Geer experienced definitely felt to them like trauma. Real or not, the incident was difficult to get past.

“I felt like it was expected that we just move on from the incident when everything experienced in the moment was real,” Geer said. “It’s pretty hard to move on, going to class and [doing] daily tasks without it affecting you mentally.”

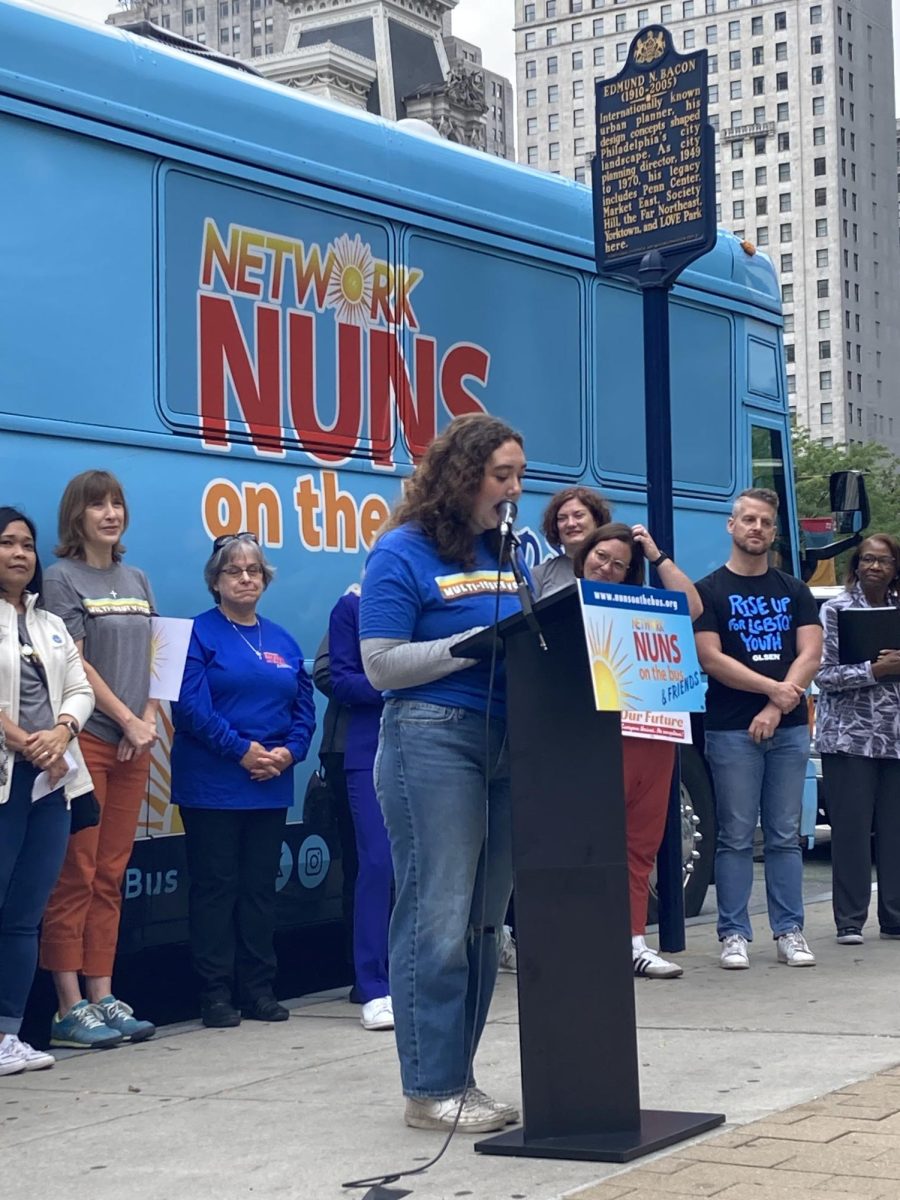

Annie Connors ’26 understands that feeling. Connors attended Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown, Connecticut. She was in third grade when the 2012 Sandy Hook mass shooting occurred, resulting in the deaths of 26 students and teachers at her school.

“I just wasn’t expecting for it to happen again,” Connors said of the March 30 incident at St. Joe’s. “I remember saying, ‘Not again, not again, not again.’ I was really scared and upset and just angry because there’s been no progress since what happened at my school.”

As in many schools across the country since the Sandy Hook mass shooting, students from elementary school through high school have participated in active shooter drills, or, as they referred to them at Sandy Hook, lockdown drills. Connors said that phrasing was purposeful so as not to “bring up those traumatic memories.”

Chanina Nugroho ’26 said she remembers her middle school and high school practicing lockdown drills. She said she utilized her prior knowledge from those drills while she was in Drexel Library during the incident. She ran to a study room to hide once the commotion started and, along with some fellow students in the room, barricaded the door with a table.

“It was really scary because a few days before that there was the Nashville shooter,” Nugroho said. “In my head I was like, ‘This will not happen in college, right?’”

Mass shootings are on the rise in the U.S., with more than 600 shootings in each of the last three years, according to the Gun Violence Archive, a nonprofit research database. Four months into 2023, there have been 173 mass shootings, resulting in over 13,000 deaths. By the Gun Violence Archive’s definition, a mass shooting includes at least four people injured or killed, not including the shooter.

Yusko said people generally have two reactions to so much violence: numbness or increased anxiety.

“You develop a numbness to the traumatic nature of all of these stories that we’re hearing of and that a lot of young people are actually living through and experiencing, so the desensitization and kind of normalization path is one potential option,” Yusko said. “Another potential option is a more emotionally and psychologically harmful option, where there’s just a growth of fear and anxiety around the unpredictability and the uncertainty of being safe in our environments.”

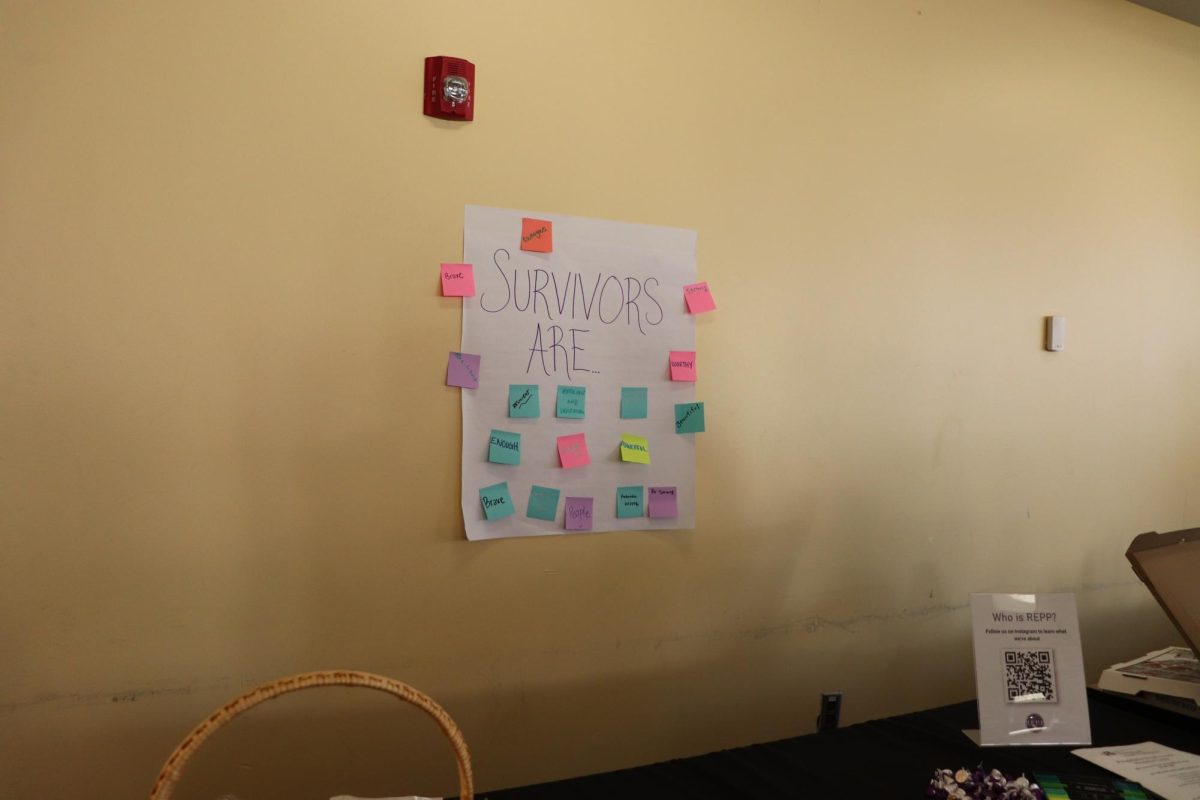

Yusko encouraged people to connect within their community to talk about what they are experiencing and feeling.

“It doesn’t have to be with a professional, but I certainly encourage people to pop into the counseling center because even one or two sessions can be extraordinarily preventive towards developing future mental health stuff,” Yusko said.

Following the March false shooter report, members of the St. Joe’s community were encouraged to reach out to Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS). When asked if CAPS saw an uptick in students seeking help, Scott Sokolski, Ph.D., director of CAPS said in a written response to The Hawk, “Although we initially received a few phone calls requesting information and support, we did not see a significant increase in requests for appointments after March 30. We continue to remain available for any students who may have been impacted.”

After Connors witnessed the Sandy Hook mass shooting firsthand, counseling was something that helped her, she said.

“I went to therapy for a very long time,” Connors said. “I think it really helps to talk about what you’ve gone through and how you’re feeling.”