Past and present students share their journeys with dyslexia.

Everyone has their own challenges they must face, some beginning earlier than others. For individuals with dyslexia, a language-based learning disability, this challenge is one to be faced each and every day.

For Will Marsh ’18, sixth grade was a defining year in his journey with dyslexia.

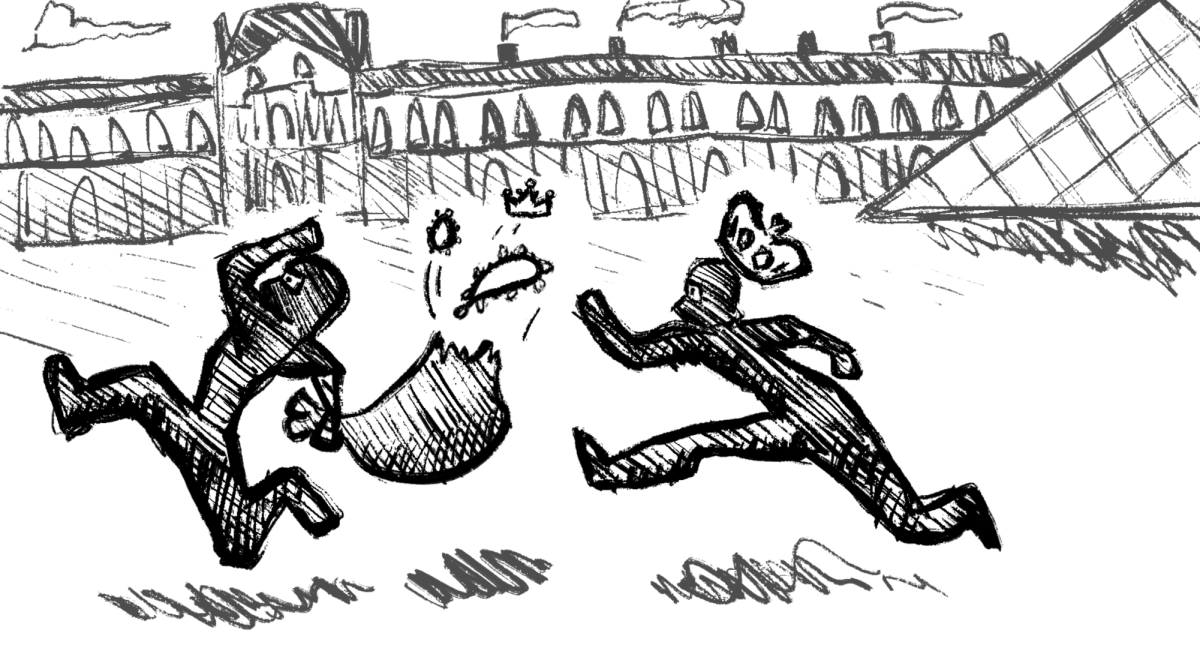

One day in class, Marsh’s teacher was discussing students’ scores for the state’s standardized test.

“I remembers feeling defeated and upset that I had a teacher who did not understand dyslexia and my processing issues,” Marsh said.

In fact, he ran from school that day. At home, he wept.

“I sat next to my bed and cried, telling myself that I was stupid,” Marsh said.

But from that moment on, Marsh said, he decided to fight to overcome future obstacles. Part of that fight is not just for him but for other people with dyslexia. Marsh become an advocate for students with dyslexia during his junior year at Union Catholic Regional High School in Scotch Plains, N.J., especially when he realized that, three years after his diagnosis, nothing had changed in his school district. Marsh planned a conference called Spotlight on Dyslexia for teachers, parents and students at Union Catholic.

Marsh has continued his advocacy at St. Joe’s, last fall participating in the 39th Annual Dyslexia and Learning Disability Conference, which the university hosted.

One in five students at St. Joe’s has a language-based disability like dyslexia, according to Christine Mecke, Ph.D., director of Student Disability Services. While many people think dyslexia is about reading words backwards, that is not the case, Mecke explained. Instead, dyslexia is often characterized by difficulties in reading, spelling and sometimes pronouncing unfamiliar words.

“More importantly for others to understand it that dyslexia is not due to a lack of intelligence but rather a neurological impairment that impacts reading skills,” Mecke said.

Abby Carlino ’19 said that dyslexia is not tied to IQ, although it may look that way from an outside perspective.

“I tell people that I am dyslexic because I do not want them to think that I am stupid because I can’t spell or read something quickly and understand it,” Carlino said. “Dyslexia is not just flipping letters around. It’s not seeing things the same way and understanding how they fit together necessarily.”

Although Carlino was not diagnosed with dyslexia until she was in high schoo as early as kindergarten, teachers wondered if she might have a learning disability. Like Marsh, she recalled her early years in school were marked by anxiety because of her struggles.

“I remember when I was little, and we had to write stuff on the board. I would get so nervous that I was going to write my words backwards or something,” Carlino said. “It would just overwhelm me a lot.”

Carlino said she has grown from these experiences, however, and that her struggles have made her a hard worker.

“I think it made me more resilient because it is a lot to overcome, especially when you are little, and everyone is excelling and reading and you are not,” she said. “It taught me to have a really good work ethic because it did take me a lot longer to understand it. I have to study two times longer than everyone else to get the same grade.”

Hailey Miller ’18, was diagnosed with dyslexia in third grade. She also worried that people would mistake her disability for laziness.

“Growing up and especially in high school, I always felt like teachers would think I’m not trying or slacking off because I wouldn’t finish my tests or homework or have to bring my classwork home,” Miller said.

Miller still struggles with such fears in college, worrying that her professors will fault her work ethic instead of understanding her struggles with dyslexia.

“I love learning,” Miller said. “It just takes me a while. Usually I’m not able to finish my work because it takes me at least twice as long as someone without a learning difference. Unfortunately sometimes that needed time is just not available.”

Reading in class is especially challenging, Miller said.

“A teacher tells the class to read [however many] paragraphs or a handout, and I’m maybe halfway through it, and since pretty much everyone else is finished, the teacher’s like, ‘okay, so who can summarize this for me?’” Miller said. “And I’m just getting anxious because I’m only halfway or less through, thinking 1) please don’t call on me right now and 2) can we have a few more minutes because I want to be able to participate and know what is going on.”

One of St. Joe’s most well-known alumni is James Maguire, ’58 who was diagnosed with dyslexia by a Jesuit professor while attending St. Joe’s. Maguire said that Hunter Guthrie, S.J., professor of philosophy, noticed that Maguire was dyslexic, took him under his wing, and helped Maguire realized his potential as a student.

“I could not read, I could not spell, and what normally look somebody a half hour to read took me an hour and a half to read,” Maguire said.

Maguire’s academic life was turned around when, with Guthrie’s encouragement, he realized he could excel with the right learning tools and with the realization that he just had to work harder than the other students.

“As a result of that, I actually became a pretty good student,” Maguire said. “It changed my perspective on myself. I always felt that I was inferior because I could not keep up with the rest of the class in studying or comprehension. Recognizing that it would take me a lot longer to read something than the other people in the class, I had to make that adjustment, and I did.”

After graduating from St. Joe’s, Maguire used what he had learned from Guthrie and applied it to the business world. Maguire founded Philadelphia Insurance Company and is co-founder, along with his wife Frances Maguire, of the Maguire Foundation.

“My dyslexia handicap never really hurt me in business because I recognized when I came out of St. Joe’s that I just needed to manage my dyslexia,” Maguire said. “I find that in meetings where there is a subject manner that has to be read, such as a legal document that has to be read, the lawyers in the room read the document and put it down, and I am still reading it. That is all right! It just takes me a little longer to do it.”

Teachers like Guthrie, who support students with dyslexia, is a key to their success, and Miller said she believes it is important to educate instructors about dyslexia so they can help their students who struggle from it.

Miller said she has found the support she needs at St. Joe’s, but she also credits her own tenacity.

“SJU is filled with tons of quality people ready to support you, and it’s okay if you mess up, just take that opportunity to learn and grown from it.” Miller said, “And if it’s an obstacle you’ll have to deal with your whole life, like dyslexia, own it, stand in your truth and discover and optimize your strengths and recognize and work on your weaknesses, with as much passion and courage of conviction as possible.”

That’s one of the important lessons that Marsh has learned over the years, too.

“One of the greatest strengths of dyslexia is our ability to persist and be resilient,” Marsh said. “We don’t back down.”