Douglas Martenson examined a large plaster piece — “Lamentation” by Adam Kraft — estimated to be from the mid-1800s, trying to decide where to start. The artwork depicts the Lamentation of Christ, when the Virgin Mary held the body of Jesus Christ after he was removed from the cross, surrounded by other mourners.

After cleaning the grime and dirt carefully with a soft toothbrush, a rag and some water, the art conservator and professor of art at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) began to in-paint, which he defined as “the coloring of the local area so that it looks consistent.” With a nylon brush in hand, he carefully touched up the plaster, avoiding changing the original look of the piece.

Martenson’s job is to conserve artwork so that it looks the way it did in its original state, which involves figuring out what materials and chemicals to use to ensure the pieces aren’t ruined.

Martenson said this isn’t easy.

“There are different ideas about how much you intervene on something,” Martenson said. “The important thing is in all conservation, even if you do hide something completely, it can be brought back to the state the conservator founded it in.”

As a professor at PAFA, a trained painter and an art conservator since 1985, Martenson was hired to help shepherd the Frances M. Maguire Art Museum toward its opening in early May 2023. His experience working with plaster cast was a selling point when Emily Hage, Ph.D., museum director and professor of art and art history, approached him about the job.

“It’s been great, and he obviously likes working with students, so that was really good,” Hage said.

Carmen Croce, director of St. Joe’s University Press and the museum’s curator, said training for a job like Martenson’s is rigorous, and the museum staff is lucky to have him.

“We were thrilled to get Doug because the only other conservators we knew were in New York,” Croce said.

Martenson said his favorite part of the process has been “seeing the pieces coming to life and bringing them back to their true state.”

Martenson likened the work of the museum coming together to a theater production.

“You go in the evening where you’ve paid to see the production and everything works out, but you know nothing about how it was all put together,” Martenson said. “The actors that were fired, the costumes that didn’t come together, the script that had to be rewritten. That’s really what we’re doing is scripting a presentation.”

When Martenson was in his 20s, he began working alongside Virginia Norton Naudé, or Ginny, as Martenson calls her, where he helped conserve a plaster for the first time in 30th Street Station, despite only having experience as a painter. He loved the project and went on to do a 20-year apprenticeship with Naudé. He did both plaster and bronze work in 30th Street Station, City Hall and on some of the pieces at the national monuments in Washington, D.C.

As Naudé got older, Martenson took on her business.

“I became the project manager, and then I started to take over the business and then she retired and I just carried on the business,” Martenson said. “That’s how I got into it.”

As an artist himself, Martenson said he sometimes struggles with leaving his creative vision behind when it comes to conserving work, but ultimately, he knows he has to leave the art the way he found it.

“You have to leave your ego at the door,” Martenson said. “Just say, ‘Ok, I understand that.’ And in your mind, you’ll be saying, ‘I should change that,’ or you see something that’s wrong with the way that the form was built on an arm or something. And you just have to love it.”

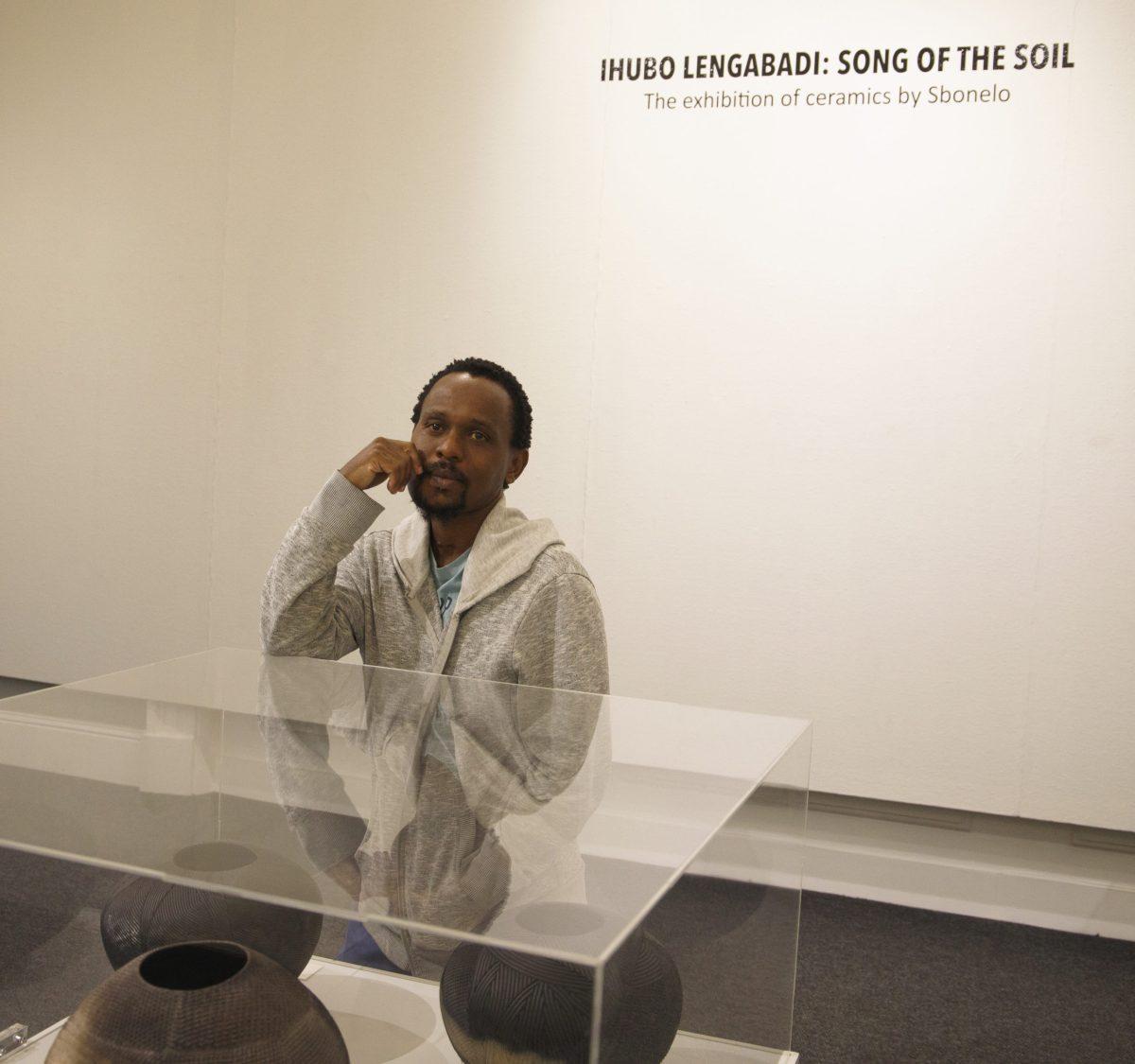

Months before its opening, Martenson anxiously watched professional art movers lift ceramic sculptures created in the 20th century to the second floor of the Maguire Art Museum. Weighing between 800 and 1,000 pounds, the fragile pieces of art were moved from a crane, through the open space between the ceiling and the top of the railing. Once the pieces were on the ground, Martenson could breathe again.

It was time to get to work.

Update: Virginia Norton Naudé’s last name has been corrected.